In a tent made of woven yak hair, a thirteen-year-old girl was stirring cheese in a cauldron over a clay hearth as blue smoke from the fire escaped through an opening in the roof. Her father had died the year before, and now her mother had tuberculosis of the bone. She was so sick and frail that her eyes—too big for her gaunt face—had an oddly fixed look. Unable to afford the necessary life-saving medicine, the girl’s elderly grandmother was praying in a corner.

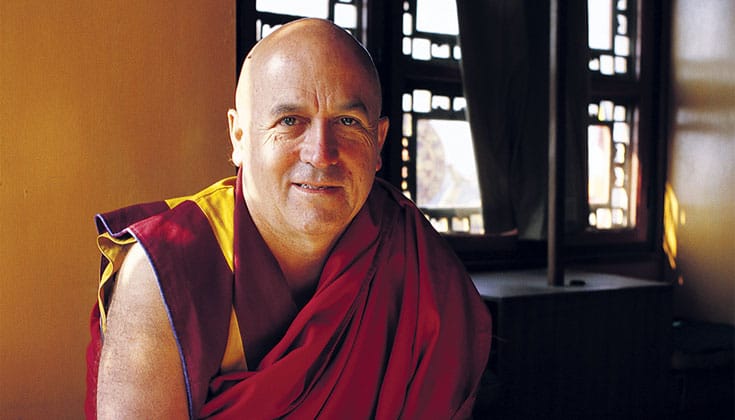

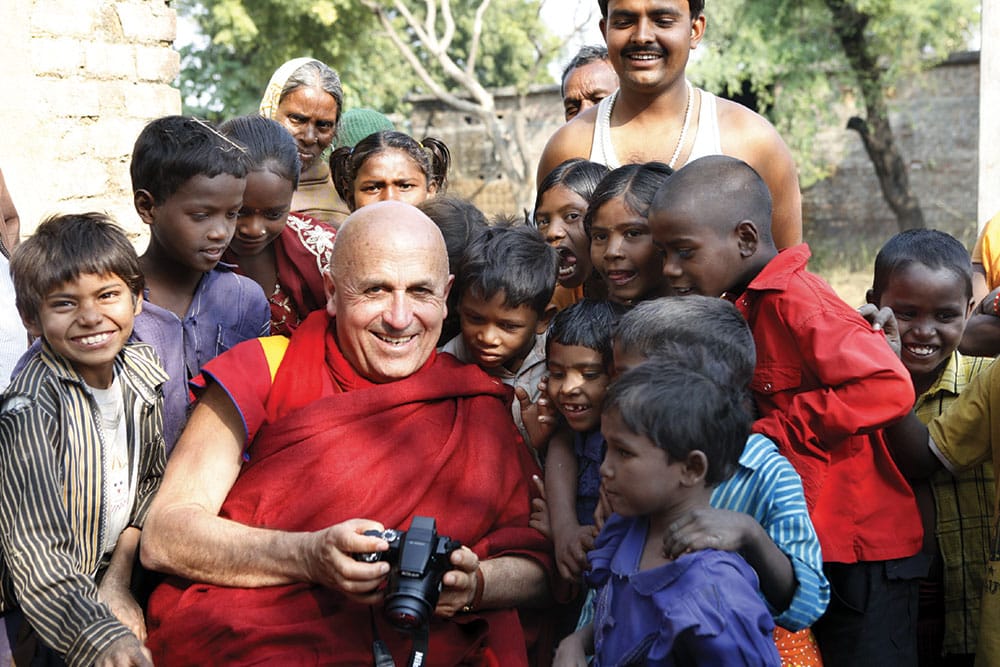

Matthieu Ricard, a French-born Buddhist monk and the founder of the non-profit organization Karuna-Shechen, came across this heartbreaking scene when he was visiting the nomadic communities of Eastern Tibet. Fortunately, he and his Karuna-Shechen team were able to help.

They gave the family a year’s supply of medicine, and—as they explained how to administer it—the young girl listened carefully with both disbelief and hope flickering in her eyes. When the team returned a year later, they found the girl beaming. Her mother was still using makeshift crutches, but she’d recovered and was no longer skeletal and bedridden.

Karuna-Shechen, founded in 2000, has been the recipient of every penny of the royalties from Ricard’s books, as well as any money he’s earned from giving conferences or selling his fine-art photography. Ricard himself lives on a shoestring—he’s slept in the same sleeping bag for thirty years and his retreat hut in Nepal has no central heating—but it’s estimated that he’s given one and half million dollars to Karuna-Shechen.

Other philanthropists have also contributed, and to date the organization has initiated and managed more than 140 humanitarian projects in Tibet, Nepal, and India. These include emergency relief to victims of the recent earthquake in Nepal, training illiterate village women in solar engineering, installing rainwater-harvesting systems in drought-prone regions, establishing a kitchen-garden program to combat malnutrition, and building new schools and improving existing ones.

Having more consideration for others is the most pragmatic way to deal with the challenges of our times.

“In this current era we are confronted with many challenges,” Ricard writes in his new book, Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World. “One of our main problems consists of reconciling the demands of the economy, the search for happiness, and respect for the environment. These imperatives correspond to three time scales—short, middle, and long term—on which three types of interests are superimposed: ours, the interests of those close to us, and those of all sentient beings.”

“Having more consideration for others is the most pragmatic way to deal with the challenges of our times,” Ricard tells Lion’s Roar. Indeed, “by meeting economists, environmentalists, psychologists, social workers, global shapers, and leaders, I realized that it is the only pragmatic answer.”

From Thomas Hobbs to Ayn Rand, the idea that humans are essentially selfish and even brutish has dominated Western thought for centuries. Ricard, however, believes that human beings are innately compassionate and that we have the capacity to be more so. There are, he says, proven methods for systematically increasing compassion in ourselves and in our society.

While Ricard is fully aware that many people will dismiss his ideas as overly idealistic, he asserts that he’s not just a nice-guy Buddhist monk who is fuzzy on facts. With sixteen hundred scientific references in Altruism, Ricard has science on his side.

Before Matthieu Ricard was a Buddhist monk, he earned a doctorate in molecular biology from the Institute Pasteur in Paris, where his main advisor was a Nobel laureate.

In 1966, when Ricard was twenty years old, his interest in Buddhism was triggered by some films about great Tibetan lamas who’d fled the Chinese invasion. Between his father, the philosopher Jean-François Revel, his mother, the painter Yahne Le Toumelin, and his uncle, the sailor/explorer Jacques-Yves Le Toumelin, Ricard had spent his whole life meeting accomplished, prominent people in a wide range of fields. Yet that didn’t prepare Ricard for these lamas.

“Great artists, scientists, philosophers, and so forth are admired for particular skills, like painting, playing the piano, or solving mathematical equations,” he says. The Tibetan Buddhist teachers, on the other hand, were skilled at being good human beings. In his words, he was “extremely inspired, extremely impressed.”

The sun allows all the crops to grow, all the fruits to mature. It gives warmth but does not expect anything in return.

Ricard got a cheap flight to India, where he met Tibetan Buddhist master Kangyur Rinpoche and spent three weeks living with him and his family in a two-room, wooden hut in Darjeeling. At that time, Ricard did not speak Tibetan and barely spoke English, so he hardly understood a word of the teachings he heard. Nonetheless, he got a sense that Kangyur Rinpoche was a bit like the sun. “The sun allows all the crops to grow, all the fruits to mature,” says Ricard. “It gives warmth but does not expect anything in return.”

For six years, Ricard divided his time between the Himalayas and France, but he felt that this was like trying to sew with a two-headed needle or stay seated between two chairs. So in 1972, after completing his dissertation on cellular genetics, he left behind his promising scientific career to dedicate himself fully to Buddhist study in Asia.

In his book Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life’s Most Important Skill, Ricard describes Buddhism as never calling for blind faith. “It was a rich, pragmatic science of mind, an altruistic art of living, a meaningful philosophy, and a spiritual practice that led to genuine inner transformation,” he writes. “I have never found myself in contradiction with the scientific spirit as I understand it—that is, as the empirical search for truth.”

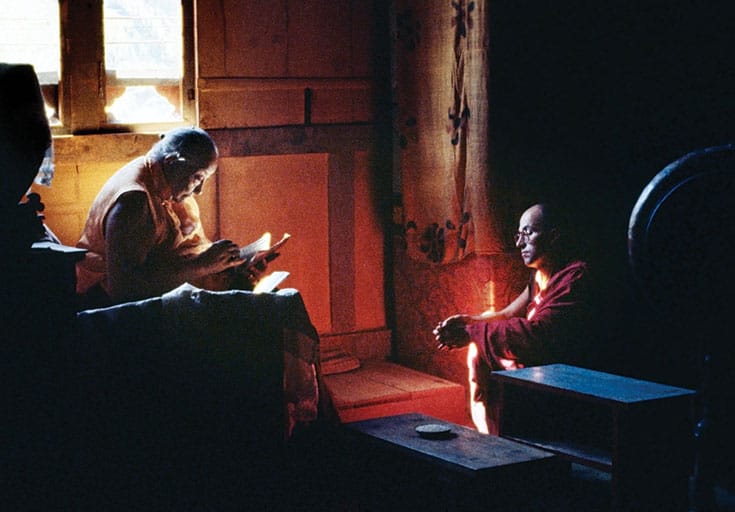

For twenty-five years, Ricard lived cut off from the wider world—no radio, no newspapers. He studied intensively with Kangyur Rinpoche until his death in 1975, and then studied with the Dzogchen master Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the twentieth-century’s most important Tibetan Buddhist teachers. He spent years in contemplative retreat.

Matthieu Ricard’s quiet, anonymous life came to an end in 1997, when a publisher proposed that he and his father engage in a dialogue unpacking the meaning the life. Published as The Monk and the Philosopher, the book was a runaway success. More than 350,000 copies were printed in France and it was translated into twenty-one languages. Ricard was thrust into renewing his ties with the scientific world.

He engaged in a dialogue with astrophysicist Trinh Xuan Thuan, which was published as The Quantum and the Lotus: A Journey to the Frontiers Where Science and Buddhism Meet. He participated in meetings at the Mind & Life Institute, an organization inspired by the Dalai Lama that was founded to encourage dialogue between Buddhist scholars and scientists.

In 2000, Ricard’s interests in science and compassion came together when he teamed up with neuroscientist Richard Davidson of the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds in Madison, Wisconsin. Ricard, in his words, “was a guinea pig” for cutting-edge research projects analyzing both the short- and long-term effects of training the mind through meditation.

For the first tests, he was confined in the noisy, claustrophobic clutches of an fMRI for more than three hours while he practiced several kinds of meditation: concentration, visualization, and compassion. For a lot of people so much time in a machine of this type would be an ordeal that could easily lead to panic, but at the end of Ricard’s grueling session, he emerged smiling. “That was like a mini-retreat!” he exclaimed.

Not feeling vulnerable, you are not trying to overprotect yourself and you are naturally open to others.

The fMRI scans revealed that Ricard and other expert meditators—those who’d practiced for at least 10,000 hours—showed extraordinary levels of activity in the left pre-frontal cortex of the brain, which is associated with positive emotions. Activity in the right-hand side, which handles negative thoughts, was suppressed. When the results of the Madison experiments were released to the public, the media gave Ricard a memorable moniker. He became known as “the happiest man in the world.”

“People often confuse happiness with pleasure,” Ricard tells Lion’s Roar. “Yet happiness is not eating ice cream. It’s a way of being, and a way of being is not just one thing. It’s a cluster of basic human qualities, among which inner freedom is central. If you’re happy, you are not the slave of your rumination. You have freedom from hatred, obsessive craving, jealousy, arrogance, etc.

“That freedom gives you inner peace and, therefore, a confidence that’s very different from narcissistic self-esteem. Because you have the inner resources to deal with life’s ups and downs, you are less preoccupied with yourself. You know that whatever happens you’ll be fine. So not feeling vulnerable, you are not trying to overprotect yourself and you are naturally open to others.

“Selfish happiness doesn’t exist,” Ricard continues. “When you’re completely self-centered—me, me, me all day long—you push away anything that could threaten your ego, threaten your comfort. This makes life miserable. You’re constantly under threat, because the world is simply not a mail-order catalogue for all your desires.”

Altruism, according to Ricard, does not require that we sacrifice our own happiness. In fact, a benevolent frame of mind, which is based on a correct understanding of interdependent reality, leads to a win-win situation. We flourish, and at the same time we are of benefit to all those around us.

For compassion, you begin by thinking of someone close to you who is suffering, and you sincerely wish for that person to be free of suffering. Then you proceed as you did for love.

Matthieu Ricard has been the Dalai Lama’s French interpreter since 1989, and he recalls how, a few years ago, he was preparing to go on retreat in the mountains of Nepal when His Holiness gave him this advice: “In the beginning, meditate on compassion. In the middle, meditate on compassion. In the end, meditate on compassion.”

To meditate on altruistic love and compassion, Ricard offers these simple instructions. “First you think about someone close to you,” he explains. “You give rise to unconditional love and kindness toward them. Then you gradually extend this love to all beings, and you continue in that way until your whole mind is filled with love. If you notice this love diminishing, you revive it. If you become distracted, you bring your attention back to love.

“For compassion,” he continues, “you begin by thinking of someone close to you who is suffering, and you sincerely wish for that person to be free of suffering. Then you proceed as you did for love.”

Concern for others is a natural part of being human, says Ricard, yet it’s also a skill we can cultivate. In Altruism, Ricard brings our attention to a pro-social game created at the University of Zurich, which gives people the opportunity to help another participant surmount an obstacle but at the risk of earning a lower score for themselves.

Two to five days prior to playing the game, participants either received a brief training in how to meditate on compassion or on how to improve memory. The experiment showed that participants who’d been trained in meditation were more likely to help. Moreover, an increase of pro-social behavior toward strangers was proportional to the period of time spent training in compassion.

Ricard tells Lion’s Roar, “In the same way that a doctor trains for six to seven years to master his or her expertise, if you want to help others, it’s not like you can just wake up in the morning thinking, ‘I’m going to change the world.’ You have to build up some qualities.”

He stresses, however, that we need to understand this about compassion: If we lack compassion for some, we risk lacking compassion for all.

“If you have compassion for everyone but, say, a certain ethnic group or animals,” he says, “then you are killing part of your empathic resonance with others. You end up dehumanizing a group of human beings or removing animals, say, from the sphere of your consideration.”

“In order to progress toward a more altruistic society,” Ricard writes in Altruism, “it is essential that altruists associate with each other and join forces. In our time, this synergy between cooperators and altruists no longer requires them to be gathered together in the same geographical location, since contemporary means of communication, social networks in particular, allow the emergence of movements of cooperation joining together large numbers of people who are geographically scattered.”

In many aid organizations, people start with the good intention to relieve suffering, then they fall prey to human shortcomings, clashes of egos, and—worse—corruption. The humanitarian aid is derailed, ending up in someone’s pocket or simply lost in bureaucratic chaos.

“The UN considers it a success if 50 percent of an NGO’s funds reaches the people it should,” says Ricard. But in the case of Karuna-Shechen, 98 percent of their funds reach their goal; only the remaining 2 percent is used to cover overhead. “I attribute this,” Ricard continues, “to the fact that we at Karuna-Shechen all share the same vision, the same kind of training and dedication.”

Karuna-Shechen recently offered three different vocational training workshops to women in India. The women were taught how to make candles and incense sticks, as well as two types of snacks. The most promising students were given further training and then, to get them off on the right foot, they were set up with a temporary candle-production unit.

The women now work from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m. six days a week and produce 150 candles a day in different colors and shapes—green Christmas trees, pink hearts, traditional Indian figurines. They receive the profits from selling their wares at local markets, plus they’re paid an apprentice salary and their food and transportation costs are covered.

Rinku is one of the women now making candles. “Learning this new craft will not only help me start my own business, it will also improve my family’s living conditions by adding income to our household,” she says. “I will use part of the money to help pay for my siblings’ education.”

If we care about the fate of future generations, we will not blindly sacrifice their well-being to our ephemeral interests, leaving only a polluted, impoverished planet to those who come after us.

The women are proud to have been selected out of all of those who participated in the initial training session, because knowing how to make and sell wares can be the difference between having and not having a decent life. Employment opportunities for rural women are few, and what is available is usually backbreaking work, such as carrying bricks or spending long hours in fields under the pounding Indian sun.

With more concern for others, Ricard writes in Altruism, “We will all act with the view of remedying injustice, discrimination, and poverty.” Furthermore, he says, “if we care about the fate of future generations, we will not blindly sacrifice their well-being to our ephemeral interests, leaving only a polluted, impoverished planet to those who come after us. We would on the contrary try to promote a caring economy that would enhance reciprocal trust, and would respect the interests of others.”

While Matthieu Ricard is a champion of altruism and compassion, he is also blunt. He wants us to cultivate benevolence. Then he wants us to do more. “If compassion without wisdom is blind,” he says, “compassion without action is hypocritical.”