From our usual point of view, health is considered being free of sickness. But we can look at health as something more than that. In the Buddhist tradition, there are three aspects of health: (1) innate, or intrinsic, health; (2) acquired, or conditioned, health; and (3) healing. Medicine Buddha practices are related to all three.

Intrinsic Health

Innate or intrinsic health—being healthy—is a state of wholesomeness. It is when we are in the original state of perfect balance, with body and mind synchronized. This state of being is fundamentally good in itself and is indestructible. It is also the source of ultimate healing. All other kinds of healing are simply temporary forms that may address only the symptoms and not the root cause of an illness or other health condition.

To bring forth the full effect and the full benefit of innate health, our minds need to have some degree of confidence or trust in this reality. It’s the same with anything we do. When we take a Tylenol, we begin by thinking, “This is going to work, this is going to help me.” We need to have some trust in that little tablet.

When our mind and body are in tune with intrinsic health, then we are unobstructed and have access to unlimited resources.

This kind of trust is not like a strong religious conviction or faith. It is a simple recognition of our own true being. At minimum, we need to have some willingness to explore this intrinsic health as a possibility. We don’t need to believe in anything, we just need a sense of inquisitiveness.

We can develop confidence in the reality of our innate health on the basis of our own experience. To bring about that experience, we use different methods of meditation and contemplation. You can also use techniques involving movement, such as yoga or running, as long as you’re not listening to music or a podcast at the same time.

The first important meditative technique for synchronizing mind and body, for getting in tune with our intrinsic health, is simply being in the present moment. Like a violinist playing a part in a symphony in which all the musicians are playing their instruments in tune and on cue, when our mind and body are in tune with intrinsic health, then we are unobstructed and have access to unlimited resources. We are joining with the innate reality of perfect balance, also known as buddhanature.

When that happens, we have a deep sense of coming home. We are free of confusion and full of relaxation. That relaxation positively affects our physical health and gives our mind strength and confidence.

Acquired Health

The second kind of health is acquired, or conditioned; it depends on many different things. We know that, in a relative sense, everything has its own time limit, after which it will not function. In Buddhist teachings, we understand that time limit as impermanence.

When harmonious causes and conditions are present, we experience good acquired health. We could also call it wellness, wholeness, or well-being. When the conditions become disharmonious, then we experience challenges. This is what the Buddhist view calls the interdependent nature. Good health and poor health alike are dependent on many different conditions, such as what we inherit in our DNA, our physical and mental habits, and the environment where we live or work. The physical elements in our body can have a positive or negative effect on our mind, while the activity of our mind also affects our physical elements.

Acquired health is determined by two key points: the immediate cause and the long-term cause.

The Immediate Cause

The immediate cause includes, for example, the bacteria in our body, our habits and tendencies, and our environment. When the immediate causes and conditions are in harmony, we experience good health. For example, some bacteria are beneficial in the right amounts, but if you have too many or too few, you have problems. Imbalance, then, becomes a cause for sickness. Perfect balance becomes a cause for health and happiness.

Buddha taught that you need three things for balance: sleep, nutrition and medicine, and meditation. We all know the value of the first two. But it isn’t only our body that needs these things, it is also our mind. Meditation becomes important in this context because it is nutrition, it is medicine, and it is sleep for our mind. Meditation is rest.

We don’t really take care of our mind as much as we take care of our body—or even our cell phone. We worry more about losing our phone than about losing our mind. We check to make sure it hasn’t been harmed, that it’s fully charged, and so on. But when it comes to our mind, we’re not doing much to care for it on a regular basis.

Meditation is a way to develop panoramic awareness, as well as a way to rejuvenate or recharge our mind. Through the practice of meditation, we can develop a fully functioning mind—a mind that can be present, that can concentrate, and that can be aware not only of oneself and one’s environment, but also of others’ suffering and their needs.

The Long-Term Cause

The long-term cause of acquired or conditioned health is connected with what we have inherited from the past. This cause may not be obvious from the outside, but when there is physical imbalance, it is often deeply interconnected with the mind and mental afflictions.

Many people today are under great stress, and that stress affects their physical health. We know that working with the mind or meditating has positive effects on hypertension, asthma, and epilepsy; it even helps in dealing with the pain of shingles. When there is a lack of control of the mind, we experience more intense manifestations of the different effects of physical sickness.

To bring about good health, we need to relate with and nourish body and mind as an integrated union; we need balance between the two. At the same time, we need to develop a sense of relaxation. When the mind gets tense, the body isn’t relaxed either. A sense of humor helps—we don’t have to be so serious. If we lose our sense of humor, then we lose the balance and begin to experience various health issues.

Healing

The third aspect of health is healing. In Tibetan Buddhism, healing is called sowa, which carries a meaning of restoring, revitalizing, and perhaps reawakening. So healing is a process of restoring the innate wholesome state that already exists.

The Buddhist idea of healing is that, through a wide variety of methods, we try to get back to our original state of innate health. If there’s nothing innately healthy, then there’s nothing to restore. If there is no original health, then what is there to bring back? Healing is not about “fixing” anything or patching something up. Rather, we try to reawaken the potential and the power of the genuine state of our subtle elements and buddhanature.

Restoring works the way a physical wound, such as a cut, heals—from inside. Slowly a scab appears, then it becomes dry and falls off, and we’re OK again. Rather than merely fixing or patching something, healing is allowing the body–mind to heal itself, to bring back the original intrinsic health by applying different methods. A bandage may help to protect the cut from getting infected, but the healing of the cut takes place from within.

Healing therefore involves changing our attitude toward health in general. We can begin by reflecting on our habits and trying to develop positive ones. I’m referring here to “habits” in a deep sense. From a Buddhist perspective, our most entrenched habitual tendency is the thought of “I” or “me,” the sense of self-centricity, ego-clinging. Of course, we all have a sense of “me” or “I.” But when that is our primary focus, it becomes a problem. We will never be satisfied or content with anything. With that kind of mind, we will experience constant irritation, discomfort, and unease.

So these are the three ways of looking at health and healing, from a Buddhist perspective: the innate or intrinsic state of health, acquired or conditioned health, and the healing process.

The ultimate healing power is something we all possess at the core of our being. Medicines and other physical substances, including good nutrition and supplements, can help us address our acquired, or conditioned, health, just as the restoration of wholesome balance can restore our innate health. But from a Buddhist point of view, this type of healing should be supported through the power of our mind.

At the same time, we must keep in mind that, from the relative point of view, this physical body we have acquired has an ultimate limit. We cannot avoid impermanence, including sickness and death. But if we can find a way back to our innate state of health, then even at the time of death, our journey can be peaceful and joyful.

The 12 Great Aspirations of Bhaisajyaguru

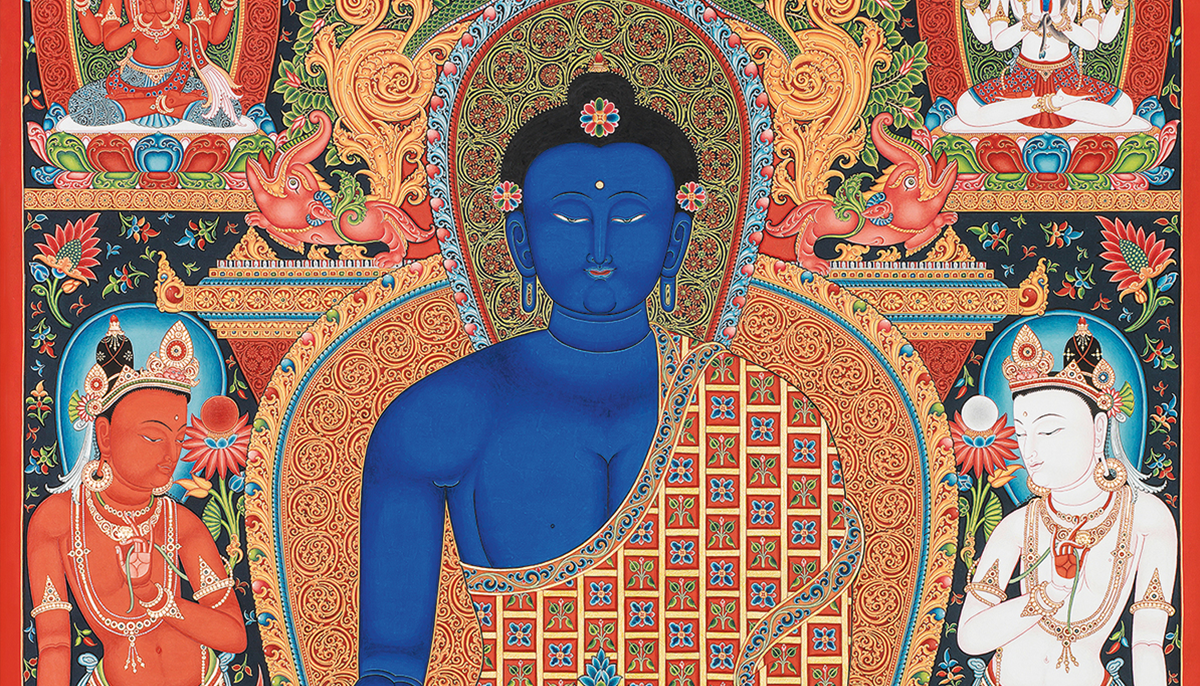

Buddha Shakyamuni taught that Medicine Buddha (Vaiduryaprabharaja or Bhaisajyaguru) made twelve great aspirations.

The first five were in regard to the principle of innate or intrinsic health.

The first great aspiration is for all sentient beings to become enlightened and for all beings to be established in the state of innate health.

The second aspiration of Bhaisajyaguru is known as a wisdom aspiration. This is an aspiration that all beings experience the blazing light of wisdom, as bright as the light of the sun and the moon.

In the third great aspiration, Bhaisajyaguru expresses the wish that sentient beings experience boundless wisdom (prajna) and skillful means (upaya), and that they become free of all mental states of impoverishment. He aspires that through freedom from mental impoverishment, there may be no worry and no rush about anything. If we don’t pacify our poverty mentality, then no matter how much wealth we have or what type of sentient being we might be, we will never be free of worry or restlessness.

The fourth aspiration is mainly in accord with prajna, the discriminating intelligence of supreme knowledge. This is an aspiration that all sentient beings—every single one of them—enter into the authentic path of enlightenment and thus connect with intrinsic health.

The fifth great aspiration has to do with perfect discipline, or in Sanskrit, sila. If we don’t have discipline, we won’t be able to achieve whatever we seek, including connecting with the perfect state of innate health. This is true in the context of worldly deeds or objectives as well. Even though we might have prajna, supreme knowledge, if we do not have discipline, we won’t be able to reach our goal. For example, we are aware of how much discipline and diligence it takes to become a doctor.

The third, fourth, and fifth great aspirations match up with the three trainings on the Buddhist path: meditative concentration (samadhi), wisdom (prajna), and discipline (sila).

The rest of the aspirations made by Bhaisajyaguru are related to acquired health and healing. The sixth, seventh, and eighth great aspirations are in connection with the physical health of the body. The ninth and tenth aspirations are concerned with the health of the mind. The eleventh and twelfth aspirations are in relation to harmonious conditions for the sustenance of health.

In order to enjoy good physical health by means of our body, it is important that all of our faculties are complete. If they are not, it is difficult to connect fully with the sense of acquired health. Therefore, in the sixth great aspiration, Bhaisajyaguru aspires that all beings come to possess full and complete faculties, with no serious difficulties in the limbs and so forth. When the physical elements of the body are disturbed, we can experience mental difficulties. So this is an aspiration that all beings have all the interdependent causes and conditions that allow genuine health to flourish.

The seventh great aspiration relates to illnesses in general. Even if we are complete in our faculties and have fully functioning limbs and so on, we can still be afflicted by various illnesses. The current pandemic is an example of this.

Bhaisajyaguru voices the aspiration that all types of illnesses be pacified. This is not only an aspiration for beings to be free from illness in general, but also that they have the harmonious conditions to heal their illnesses. Many people are impoverished and have difficulty acquiring the medicines or other things that will help them heal. To address this, we can make aspirations that all beings come to possess health insurance, for example.

The eighth great aspiration relates to people who may be discontented with their current faculties with regard to gender. For those who have a state of mind that does not feel harmonious with their assigned gender, for those who may wish to depart from that gender and have a different gender identity, Bhaisajyaguru aspires that their wish be accomplished.

In the original version of the eighth great aspiration, only women were mentioned as possibly wanting to relinquish their gender. But my guru, Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso Rinpoche, taught that women were only an example in this aspiration and that it therefore applies to all beings who may wish for a different gender identity. In Khenpo Rinpoche’s interpretation, the eighth great aspiration applies to women, to men, or to beings with any type of gender as well as no gender.

The ninth and tenth aspirations are both connected to mental health. The first part of the ninth great aspiration is that sentient beings be liberated from the “lasso of Mara.” Here, Mara represents the eight worldly dharmas, and the lasso represents being bound to those dharmas, which are 1) attraction to comfort and 2) aversion to discomfort; 3) attraction to gain and 4) aversion to loss; 5) attraction to praise and 6) aversion to criticism; and 7) attraction to fame and 8) aversion to anonymity. If we’re governed by fixation on those eight dharmas, it is as if we are bound by a rope. This is a crucial point regarding the restoration of mental health.

The second aspect of this aspiration is that sentient beings become free from clinging to certain views and social ideologies. For example, we can see how disputes arise due to different religious traditions and views. So this aspiration says, “May all of these types of disharmony be pacified.” Once this pacification occurs, the aspiration says that Bhaisajyaguru will then teach all sentient beings “the conduct of bodhisattvas”—the view, meditation, and action of benefiting others.

The tenth great aspiration relates to those who fear, who are beaten, or who are otherwise harmed by a “fearsome sovereign.” Bhaisajyaguru aspires that they be completely emancipated from all harm. This wish is made bearing in mind all beings who are treated this way, whether or not they are guilty of any type of wrongdoing. The main focus of this aspiration, however, is sentient beings who are experiencing injustice.

In the eleventh aspiration, Medicine Buddha voices concern for those beings who don’t have the necessary provisions for sustaining their body and their health, such as food. He makes an aspiration that they have everything they need for sustenance, and he also makes the aspiration to establish beings in genuine happiness. “Happiness” here does not just refer to the things that beings enjoy or that bring health—Bhaisajyaguru’s aspiration is also that beings understand and embrace the causes of health and well-being.

Number eleven also includes an aspiration that all of the activities needed to obtain any necessary items be connected to virtuous actions, and not connected to nonvirtuous actions. After all, if we help ourselves in a way that harms others, that’s not going to be good for ourselves or for them. Further, Bhaisajyaguru aspires not only that beings obtain the items they need to sustain their bodies, but also that they obtain the items they need to sustain their minds. We need excellent and abundant wisdom, compassion, and loving-kindness.

Last, in the twelfth great aspiration, Bhaisajyaguru prays that beings have clothing and wealth in precise accordance with their needs. Along with that, he aspires that sentient beings’ wishes be fulfilled. Whatever types of wishes they have—clothing for protection or adornment, beautiful music, sweet incense—all will be fulfilled.

What does this teach us? It shows that being able to satiate our desires is important. If we have sought something and then receive it, we must allow it to satisfy us. If we do not allow ourselves to be satisfied, we will constantly strive without enjoyment, which leads to a lack of contentment, the defining state of samsara.

In the Buddhist view, aspirations are equivalent to prayers. They have a very similar meaning. We bring a particular desire to mind, and then we express it in words and sounds that are harmonious with that objective.

The desire for accomplishment, brought together with words, is aspiration. We could say that an aspiration is a verbalized dream. As we make our own aspirations, we have to believe they are possible—we have to trust in our capacity to attain or materialize those dreams. Aspirations have great power; they bring great blessings. In these twelve great aspirations, we see the dream of Bhaisajyaguru for the benefit of all beings.