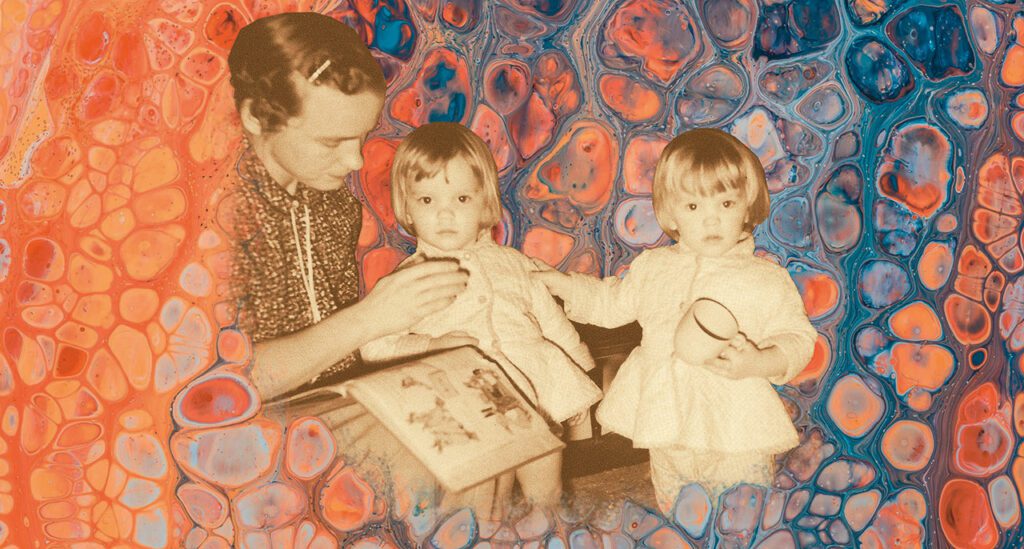

When my siblings and I were little, before the divorce that brought us a sliver of safety, we didn’t have the words to talk about our father. The language we needed came later: physical abuse, attacks without warning. He was always the victor in those battles, we the defeated, until our mother got a job and pushed him out.

Morty had only worked intermittently before the divorce; afterwards, he refused to pay child support. Our mother had a good job, but it wasn’t enough to raise three kids on her own, and she was lonely. She was beautiful and smart, but no man wanted to take on three kids. She came home in the evenings and drank and cried.

As children we told each other we hated our father. As adults we said he robbed us of our childhood. Those were the things we told ourselves, and each other, when we spoke of him. But mostly we tried to forget he existed.

My brother cut off all contact with him very early on. My sister lasted a little longer before she gave up. For reasons I can’t explain, I stayed in touch, although I kept him at a distance. I moved from New York to California; I saw him on trips back to New York, about once every two or three years. Of my three children, he met only my first-born, but she was an infant then. She has no memories of him.

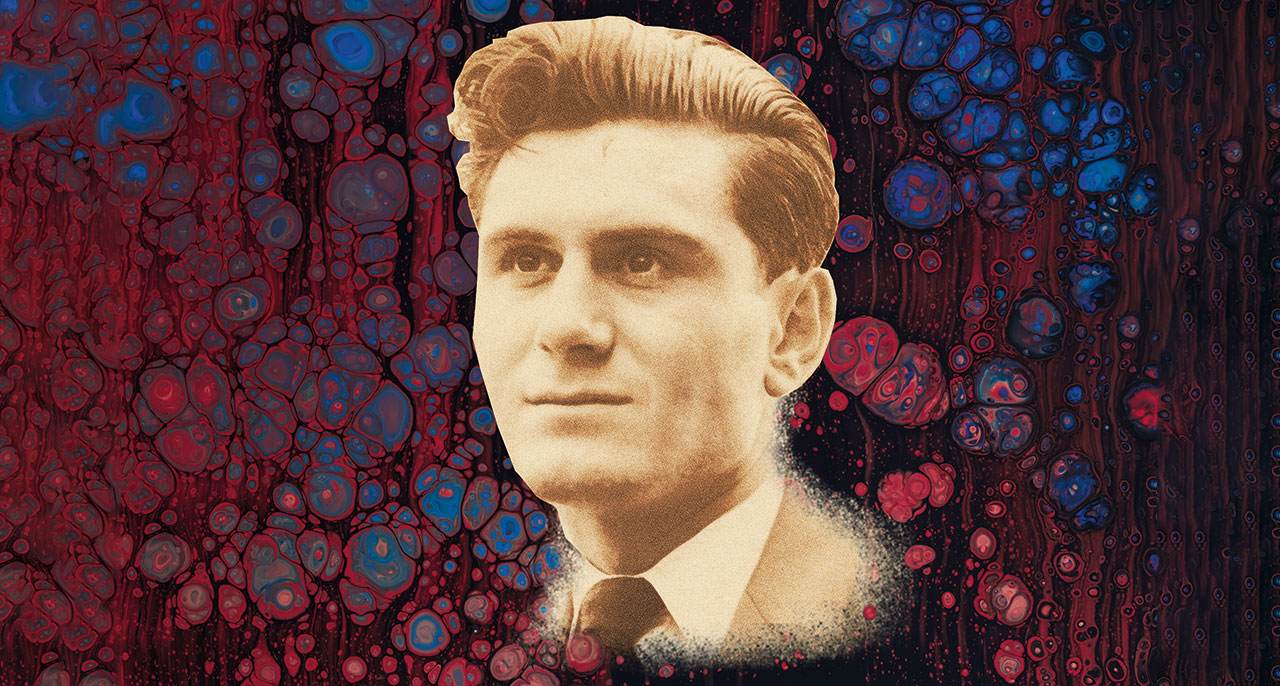

By the time he was seventy, he’d succeeded in alienating everyone in the family, including his closest sister, our Aunt Elaine. That was a real feat of alienation, because Elaine was a devoted sister. I knew, because he’d told me, how important Elaine was to him. Their father had been a celebrity, the conductor of the Your Hit Parade radio program, and friends with Frank Sinatra; he wasn’t home a lot. Their mother died when my father was thirteen and Elaine was eleven, and the woman their father married three years later was by everyone’s reckoning a real bitch. They lived in a mansion on the water in The Great Gatsby’s West Egg, but it couldn’t have been a happy home. It was Elaine and Morty against the world until my dad enlisted in the Air Force right out of high school in 1943.

When he returned from the war a broken man, his sister Elaine was there to help, and she continued for decades, in all sorts of ways. But what could Elaine do when Morty issued an edict pronouncing her husband Phil persona non grata, demanding that the family choose between them: if anyone so much as spoke to Phil, they would automatically go on Morty’s shit list.

It was insane. Elaine was dying of uterine cancer while Phil took care of her at their Manhattan apartment. If anyone wanted to see Elaine, they automatically saw Phil. What were they going to do, not say hello? And Phil’s offense, if one could call it that, was all in my father’s head.

I’d received the letter too, just like everyone. Who did he expect me to choose? On my next trip to New York I went to see Elaine.

“My father’s crazy,” I said to Elaine, as if she needed telling. “Do you want me to talk to him, get him to understand?”

“Don’t bother,” she said. “He’s too much trouble.”

Elaine died a few weeks later, and I flew out again to attend the memorial service. My father wasn’t there, but that’s what I’d expected. I assumed nobody told him about the memorial service. I certainly hadn’t. None of us wanted a scene. If he came, who knew what he would do?

He was eighty when he died, of an untreated dental abscess—he’d refused to fill the prescription for antibiotics the dentist gave him. In the days following our father’s death, my sister and I told each other privately that our first feeling after we heard he was dead was relief.

How he got by financially was a mystery, given his resistance to taking a regular job. When we were kids, he’d spent more time unemployed than employed. Every job ended soon after it began: he’d quit because he thought someone was treating him unfairly, or he’d get fired. He was a writer and an inventor, but the one novel he’d published, about his experiences as a POW in Germany, had gone out of print years ago, and his inventions never made any money.

For years we’d worried that he would end up on the street and we’d have to find a way to take care of him. We couldn’t take him into our homes—the psychic imprint of his hard hand on our body’s memory was still too fresh—and neither of us had the extra tens of thousands of dollars a year that it would take to house him. Now we didn’t have to worry about that.

Seven years after Morty’s death, I got a call from a man who had founded a not-for-profit called Purple Hearts Reunited. Their mission, Captain Zak explained, was to return lost medals to their rightful owners, and a Purple Heart had been found with my father’s name on it. With my permission, he’d give my contact information to the people who had the medal so they could mail it to me. It arrived a week or two later, and a few days after that, Captain Zak called to confirm I’d received the Purple Heart, and to ask if he could put out a press release. I told him to go ahead.

Some weeks later, I was sitting in a café when my phone rang. It was a journalist; she’d seen the press release and wondered if she could interview me. I closed my laptop and went outside so we could talk.

We spoke for almost an hour, with me pacing back and forth on the sidewalk in front of the café, keeping an eye on my table. She wanted to know what my father was like. That put me in a bind. What could I say that wouldn’t sound bad? Finally, I said he was a little difficult. She asked if he’d talked much about his experiences in the war. He’d told us nothing, I said.

“Your experiences are similar to those of the children of Holocaust survivors,” she said.

“My father was in a POW camp, not a concentration camp,” I said.

We argued about that for a bit until I finally understood the point she was trying to make: what my father went through, how it affected him, his refusal to talk about it afterwards, and the impact on our family life—all of it was similar to what survivors of the Holocaust experienced. I’d told her my father was Jewish, and an enlisted man. Both, she said, were relevant. The officers might have been treated better in the camps, but not enlisted men like my father, and certainly not Jewish ones. My father’s dog tags would have given him away.

A few weeks later, she sent me a link to her story on the newspaper’s website. She’d dug up a memoir by the captain of my father’s crew telling the story of what happened after their plane was shot down. I filled in the rest with my own research.

The camp my father had been taken to, Stalag Luft IV, was infamous for its terrible conditions. But as horrific as the camp had been, the death march that followed was even worse. In late January 1945, as the Russians approached from the east, the Germans pushed the prisoners of Stalag Luft IV out onto the road to retreat west, deeper into Germany. It was the worst winter on record, men drank from ditches that others had used as latrines, dysentery was rampant. They covered six hundred miles in three months, sleeping out in the open. They ate grass and grain stolen from farmers. Some men ate rats raw. Those who could not keep up were bayoneted or shot; those who survived were walking skeletons. I’d seen the bayonet wounds on my father’s chest, but I hadn’t thought about what they meant.

The article on my father was published as I was waiting to find out if I had uterine cancer. I’d started attending a class on Buddhist meditation at a church in Berkeley. It was led by Insight Meditation teacher James Baraz, based on his book Awakening Joy. I was waiting for the results of the biopsy when the article appeared.

I was thinking about my father and that article when Baraz led us in the Buddhist practice of metta. Metta is a Pali word for which there is no exact equivalent in English. It means loving-kindness, compassion, goodwill, and more. The idea behind metta is that by cultivating a spirit of goodwill toward the world, beginning with yourself and moving outward to all living beings, the negative crap that gunks up the works in life can be flushed out.

Baraz had us close our eyes and repeat to ourselves: May I be happy. May I be well. May I be safe. May I be peaceful and at ease. This might seem trivial, but it’s not. To extend metta to yourself, you have to stop hating yourself.

Then he told us to pick someone close to us, a child or a friend, and repeat these words to them, in silence: May you be well. May you be safe. May you be peaceful and at ease.

Then he had us choose was a person we felt neutral or indifferent toward: May you be well. May you be safe. May you be peaceful and at ease.

Lastly, he said, pick someone who’s hard for you.

I picked my father. It wasn’t planned. It just happened.

I saw him in the POW camp. He’d gone into the service when he was eighteen. My son was already in his twenties, but I remembered him at eighteen. He was just a boy. I imagined my son in the camp, knowing how frightened he would be, and all the compassion that was so easy for me to feel for my son spilled over onto my father.

I hadn’t realized until then how young my father had been when he was captured. I wanted to comfort him. He was dead, so I couldn’t, but still I wanted to. Just like that, I stopped being angry at my father. I understood then that all of his brutality could be explained as a kind of PTSD, the aftermath of that horrific year when he was so vulnerable. He drank to try to get away from his memories, and when he was drunk he did terrible things. But that didn’t mean he didn’t love me. He was just terribly messed up.

I don’t know how long we stayed in that last segment of metta practice, but Baraz must have let it go on longer than the other segments. Perhaps he knew what might happen to people like me, confronting long-held resentments and anger, coming to terms with our pasts.

I’d focused so completely on how my father hurt us, physically and emotionally, and on how he’d abandoned his responsibilities as a parent, that I’d stopped seeing anything else. Now when I looked, I saw that I’d gotten so much of who I am from him. For good or for bad, my brain works much the way his did. The wacko spirit that was an indelible part of my father was also in me. The creativity that fired my science and my art came from the same genetic stuff.

I cried and cried, sitting in the pew in that church. After some time, I found myself telling him I was sorry because I’d added to his pain. I didn’t blame myself—there would be no end to recrimination if I couldn’t accept that I was human and had needed to protect myself. But I stopped being angry at him that night, and I began loving him again.

Verse 3 of the Dhammapada instructs us that if we want any kind of spiritual well-being, we have to cease our endless rehearsing of the list of the debts others owe us. It says, “He abused me, attacked me, defeated me, robbed me!” For those carrying on like this, hatred does not end.

Why do we have such a hard time letting go of life’s debts? Do we think we’ll ever really collect on them? It’s as if we think that the universe owes us, big time, because of the injustice we’ve experienced: the violent father or the cold mother; the partner who betrayed our trust; the entire society who turned against us because of the color of our skin, or our religion, or who we love. If we forgive that debt, haven’t we thrown away a massive IOU?

Part of the trick to giving up the debt is to recognize, first, that it’s uncollectable, and second, that to hold onto those IOUs is an unbearable burden. As Buddhaghosa, the fifth-century Buddhist commentator, wrote about holding on to anger: “By doing this you are like a man who wants to hit another and picks up a burning ember or excrement in his hand and so first burns himself or makes himself stink.”

Giving up that treasure chest of IOUs can be easier when we realize that suffering is universal.

Kisa Gautami was the mother of a young child who had died. Desperate, she went to the Buddha and begged him to bring her son back to life. The Buddha listened compassionately and after she finished speaking he told her to bring four or five mustard seeds from a home that had never known death. She went off, rejoicing that her son was to be restored to her, but in home after home, the message was the same: every family had lost someone they loved. That realization did not bring her son back to life, but it did bring peace to Kisa Gautami. She returned to the Buddha and became his disciple.

Understanding that our private pain is universal has two main outcomes. First, it heals the part of our pain that comes from feeling isolated, by telling us: You are not alone.

Second, it gives us an opportunity to gain empathy for others. James Baldwin wrote in his short story “Sonny’s Blues” about the broken relationship between two brothers. The narrator, a high school math teacher, had kept to the straight and narrow while his younger brother, the titular Sonny, had not. Drugs brought Sonny down, landing him in prison and bringing dishonor on the family. The older brother turned his back on the younger until his own daughter died of polio, at only two years old. On the day that the little girl was buried, wracked with grief, the older brother thought of Sonny, alone and in prison, and it was only then that his heart opened. His own pain, he wrote, made his brother’s pain real.

Viktor Frankl, the author of Man’s Search for Meaning, wrote about what he experienced in Auschwitz and other Nazi death camps. In language that is surprisingly similar to many Buddhist teachings, he wrote of the inevitability of suffering. But some prisoners, he wrote, were able to see the camps as an opportunity to grow spiritually.

“In the final analysis,” Frankl wrote, “it becomes clear that the sort of person the prisoner became was the result of an inner decision, and not the result of camp influences alone. Fundamentally, therefore, any man can, even under such circumstances, decide what shall become of him—mentally and spiritually.… It is this spiritual freedom— which cannot be taken away—that makes life meaningful and purposeful.”

I live in Amsterdam now, not far from Rotterdam where my father and his crew jumped from their burning plane and were handed over to the Germans. Amsterdam is filled with memorials of World War II. The Anne Frank House is a short walk away from my apartment, and the Holocaust Museum is just a little further.

Every year, on Remembrance Day, Amsterdammers gather on Dam Square for two minutes of silence to commemorate all who died in the war. I go stand with others and remember my father. He didn’t die physically, but something of him did die then, and we children bore the wounds. If I hadn’t already found a way to process my father’s impact on my life, living here would compel me to.

Now, when I think of him, instead of the anger I felt for so many years I feel a mixture of love, pity, and regret. I regret that my rejection of him added to his pain, that I never really got to know him. But the story I’d told myself, and others, for so many years—that I was abused, beaten, terrorized—that’s somehow gone. It may be factually true—he did abuse us, attack us, defeat us, rob us of our childhood. But the meaning of it is different now. The opening in my heart that happened in that church in Berkeley is still there. And when I think of my father, even when I think of him beating us, I feel metta for him.