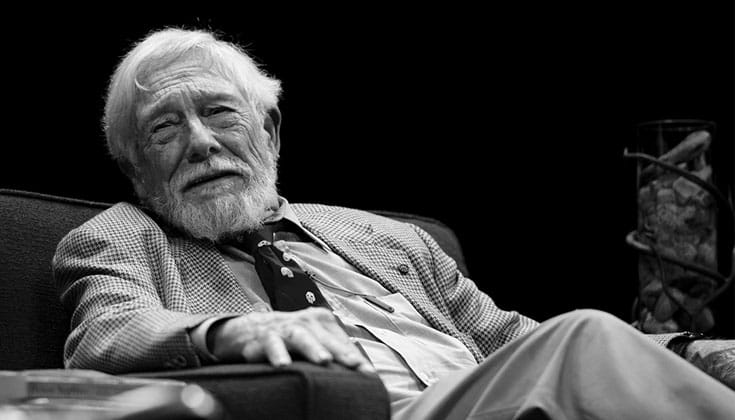

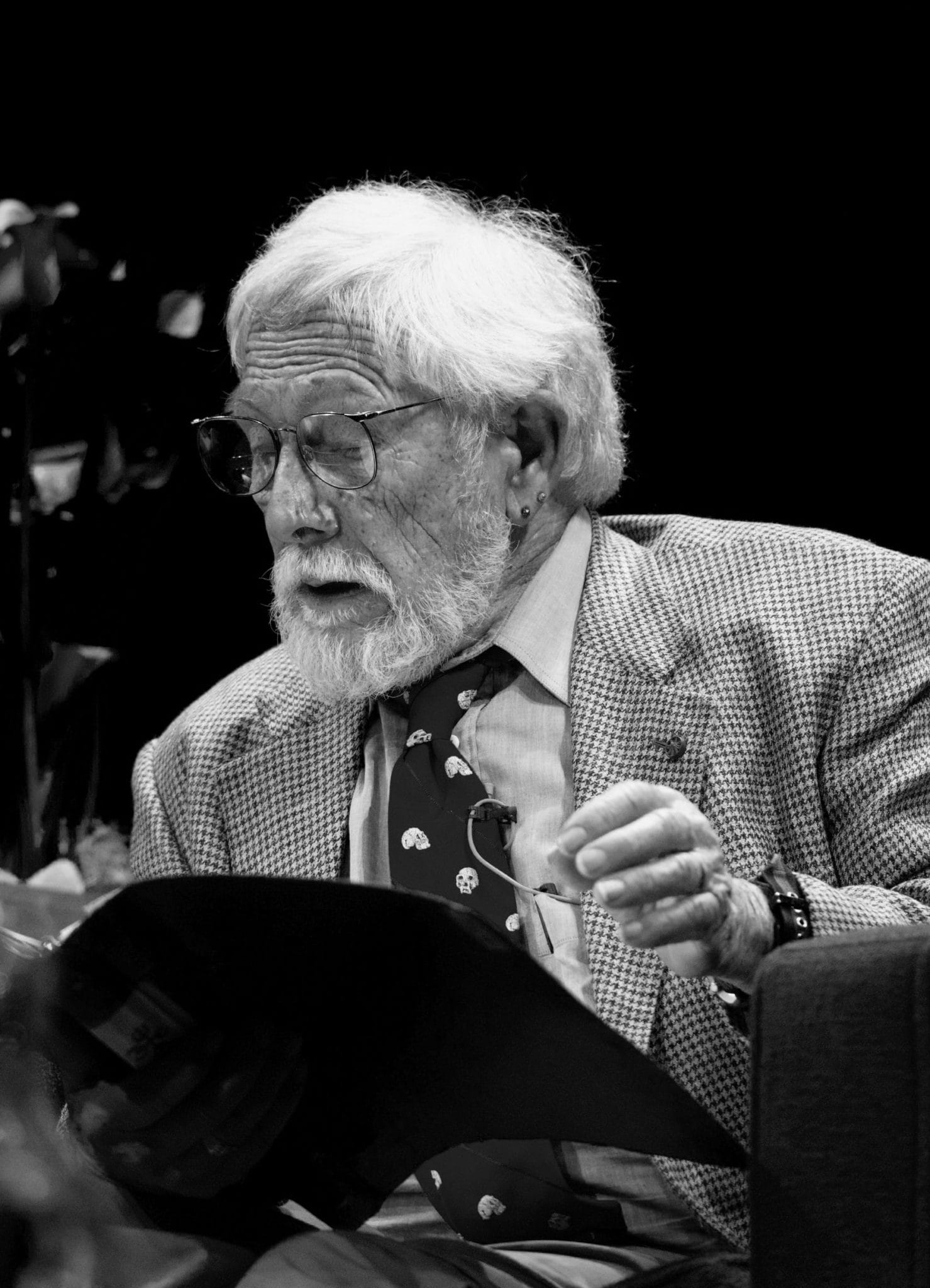

Shortly after his eighty-fifth birthday, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, naturalist, and all-around Renaissance man Gary Snyder read from his latest (and possibly last) collection of poems, This Present Moment, as part of the City Arts and Lectures program at San Francisco’s Nourse Theater. He drew an interesting crowd of young techies and older hippies. Actor and activist Peter Coyote, who credits Snyder with introducing him to Zen, asked a question from the front row; Michael McClure, who had read along with Snyder and Allen Ginsberg at the legendary Gallery Six reading in SF in 1955 was there; and California Governor Jerry Brown, who appointed Snyder to the California Arts Council during a previous term, attended both the reading and a small after-party held in the poet’s honor. Shortly after that evening, I spoke to Gary Snyder. —Sean Elder

When I was in high school, young people were still carrying copies of Jack Kerouac’s novel The Dharma Bums around in their backpacks. After its publication in 1958, you found yourself identified with Japhy Ryder, the fictional character Kerouac based on you. Did that annoy you?

The Western Buddhist world, however it is, has to live with The Dharma Bums. I don’t have to live with it too much—people don’t talk to me much about it anymore.

Jack was a novelist; he wasn’t a journalist. I am only one small model for the Japhy Ryder character. A lot of what Japhy Ryder does is fictional, but some of it is interestingly drawn on what Jack and I did together—the mountain-climbing scene is close.

I learned somewhere that Buddhists and Hindus included all the different creatures in their moral concern, and I said, “Well, that’s for me!”

As a piece of writing, The Dharma Bums is not one of my favorite Kerouac novels. It was written too hastily, and you can see the haste. He just banged it together because his publisher said, “On the Road is doing so well, let’s have another novel right away.” Jack sort of got into that, so as a writer you have to be careful what your publisher needs. Turns out that On the Road is the all-time bestseller in the Kerouac oeuvre, and The Dharma Bums is the second best.

I think On the Road is a very fine piece of work. The Subterraneans is a wonderful book, and Dr. Sax is charming, a playful, youthful piece. Both of those I like better than The Dharma Bums.

Can you talk about your relationship to the Beats? Was there any sense at the famous Six Gallery reading in 1955—where Allen Ginsberg first read “Howl” and you read “A Berry Feast”—that this was the beginning of a movement?

There was already a movement. I was very much a student of the poet and essayist Kenneth Rexroth. He had an open seminar twice a month in his apartment out in the Avenues district of San Francisco. I got over there and listened to what Kenneth had to say. It was from Kenneth that I first heard discussion of labor unions, the anarchist movement, the history of West Coast Communism. The circle of people around Kenneth were part of my continuous education in the history of the West Coast left. Kenneth in his earlier days had gone to all the early meetings of the Italian Working Men’s Circle on Potrero Hill. He had a lot of crazy opinions but also had very good insights.

The first time I met Allen Ginsberg was at Rexroth’s house—Allen had just come up from Mexico. The first time I saw Kerouac was when Allen brought him to Rexroth’s place. Because Allen was living in Berkeley, I saw more and more of him. Kenneth thought of both Jack and Allen as “talented jerks.”

Was that his phrase or yours?

I don’t remember. They weren’t quite grown up yet.

What was your first exposure to Buddhism?

I had a definite argument about the ethics of Christianity—or the absence of what I thought was ethics—in their inability to extend concern to non-human beings. That’s when I quit going to Sunday school—when I found out that our heifers that died couldn’t go to heaven. Then I learned somewhere that Buddhists and Hindus included all the different creatures in their moral concern, and I said, “Well, that’s for me!”

The first big hit of East Asia that came to me was at the Seattle Art Museum, which had a wonderful collection of East Asian, Chinese, and Japanese landscape paintings. Looking at the Chinese and Japanese mountain landscapes, my thought was that they sure looked a lot like the Cascades in Washington. I also thought, “Gee, these guys really knew how to paint!”

When you look at a European landscape, it might seem familiar if you live on the East Coast, but it was a very unfamiliar landscape to me. East Asian painting covers a mountain landscape with ice and rocks and clouds that looks very much like the landscape of interior Washington.

I ran into Buddhism again in college, partly through anthropology and world humanities courses, and partly through the presence of one Chinese gentleman who had been in the American army in World War II and was going to Reed College on the GI Bill. He was an expert calligrapher in both Chinese and the Roman alphabet.

I managed to make my way to Japan and stayed there for twelve years.

After one semester at Indiana University studying linguistics, I went to Berkeley and started studying Chinese full-time. Then I went to Asia with the goal of studying with a Zen teacher. By that time, I had narrowed my territory to Zen Buddhism—its particular kinds of discipline, its poetry, and its heart. I managed to make my way to Japan and stayed there for twelve years.

How were you embraced as a Westerner?

As long as you speak the language and have good manners, you can go anywhere. At first they think you’re a little odd and then they get used to you.

Were you in monasteries?

I was partly in monasteries and partly living in a little place nearby. I had to do that because I needed to be able to look things up. They don’t have a library or a dictionary in a Zen monastery, so I had a place just a ten-minute walk away. To pay the rent I took on conversational English teaching jobs.

Part of the time I was very much in the Buddhist world, but also I got to know Japanese intelligentsia and various European and American expat types, the bohemian subculture of western Japan. I learned a wide variety of Japanese that way: from Zen Buddhists, who speak the most learned and polite Japanese when they want to, all the way down to the dialect of the southern part of Kyoto, which has gambling and prostitution and bar zones. They have quite a vocabulary too. [Laughs]

You were raised on a very small dairy farm outside Seattle in what you described as “a hardscrabble rural poverty life.” Would you say that existence informed you politically?

When I say “hardscrabble poverty,” I’m just talking about the Depression. Everyone was poor, everyone that we knew. My dad was out of work for eight or nine years, but we did all kinds of other things, including splitting shakes, cutting old cedar stumps off close to the ground. We had chickens and cows and eventually fruit trees.

I never had a consciousness of poverty until later, when I realized there were people who have it a little easier. But compared to the kinds of poverty you see in other parts of the world, we always had a car that ran, at least. It’s all a matter of degree.

For a poet and a writer like myself, you can’t help but be a public intellectual. People ask you for your opinion whether you have one or not.

You have to understand that the whole Northwest was much more left wing than it is now; the whole country was more left wing. On the western side of Washington and Oregon there were a lot of proto-socialists and downright Marxists. I sat around and listened in on a lot of conversations. My father was part of the League of Unemployed Voters, an early Seattle mutual aid association that had cooperative auto repair shops, cooperative food stores. It was flourishing so well that some people say it was why President Roosevelt started the New Deal welfare programs—because he didn’t want the West Coast to go Communist.

How would you describe yourself politically now, or do you?

Self-definition is presupposed before we start talking politics, which is also to say: What picture of the world have you managed to create for yourself? For a poet and a writer like myself, you can’t help but be a public intellectual. People ask you for your opinion whether you have one or not.

Tell me about your early interest in Native American culture and traditions.

Our farm was at the north end of Lake Washington near Puget Sound, still home of many Salish groups of Native Americans. At Pike Street Market in Seattle, down at one end where the Hmong women sit now selling embroidery, there were Puget Sound Native Americans sitting on blankets on the ground, selling blackberries, huckleberries, and dried fish. That was part of my world when I was a kid. I was fascinated by the anthropology museum at the University of Washington—my parents would drop me off there when they were going shopping in that part of town. I took note of all that cedar carving and so forth, and talked to Native American guys when I could. So it was a sort of an easy, gradual move from an interest in Native American culture to an interest in East Asia.

Both interests—Native American culture and Buddhism—were later embraced by a lot of young people in the sixties and seventies. Did you see yourself as sort of a trailblazer in that regard?

I had no intention of that. Most of what I see, I think, “They’re not doing a very good job of it.” But I appreciate the steadiness of a lot of the Buddhist people. I have a current companion and she practices vipassana meditation. She asked me, “What is the relationship of vipassana to Zen?” I said, “Vipassana is like going to college. Zen is graduate school; you really get down to where you’ve got to make it work.” I think she’ll probably find her way into Zen eventually.

Of all the things I do, poetry is the one I think I do well.

The one thing I haven’t talked about, and I should say something about, is poetry. Of all the things I do, poetry is the one I think I do well. I’ve been watching what poetry can be for a long time, and part of it is orality. Poetry is very old—it predates

writing and literature. That’s also part of my linguistic and anthropology background—I learned to appreciate nonliterate cultures and prehistory, and what is now called deep history.

Years ago when we were young, Jim Harrison and I did a poetry reading tour in upstate Michigan. It was a pilot program to see if poets in the schools might be a viable idea, to see if students would sit still and listen to poets talk about poetry. That was before Jim wrote short stories.

The kids enjoyed it a lot. For one thing, we said bad words. Poetry gives you permission to say any kind of language, using any kind of grammar. One of my neighbors has been doing poetry classes for children for years. He says, “One of the first things I do is I tell all the children in the third grade, ‘Write a lie.’ They love it. They say, ‘You mean we can write something down that’s not true?’” It’s a wonderful permission.

You’ve said that your new collection of poetry, This Present Moment, will be your last. Does that mean you’re not continuing to write poetry?

You don’t plan to write poetry. If it comes to you, fine; if it doesn’t, that’s fine too.

It took me ten years before I felt like I could let this collection go. I’ll be writing some more, of course, but I don’t think I’ll be putting together another collection. In fact, I’m gearing up to do a new prose book taken from a history of the environment of China I was working on in the 1970s. Most of it is already written. Its title is The Great Clod, which is a Chuang Tzu line. He was a contemporary of Lao Tzu’s, the other great creative Taoist writer. He says, “The great clod nourishes me, comforts me, chills me, feeds me. If I appreciate my life I should appreciate my death.”

You also said that you weren’t sure if you liked This Present Moment. Have you made up your mind about its merits?

Its strength is that I let it be imperfect. [Laughs] That’s what I’m learning. There’s a Japanese saying: “Imperfection is best.” That’s one of their aesthetic sayings. I decided I’m not going to hold it down to the line and get it just right. There are things in there that I don’t know what I think of. But people like it; I can see that.