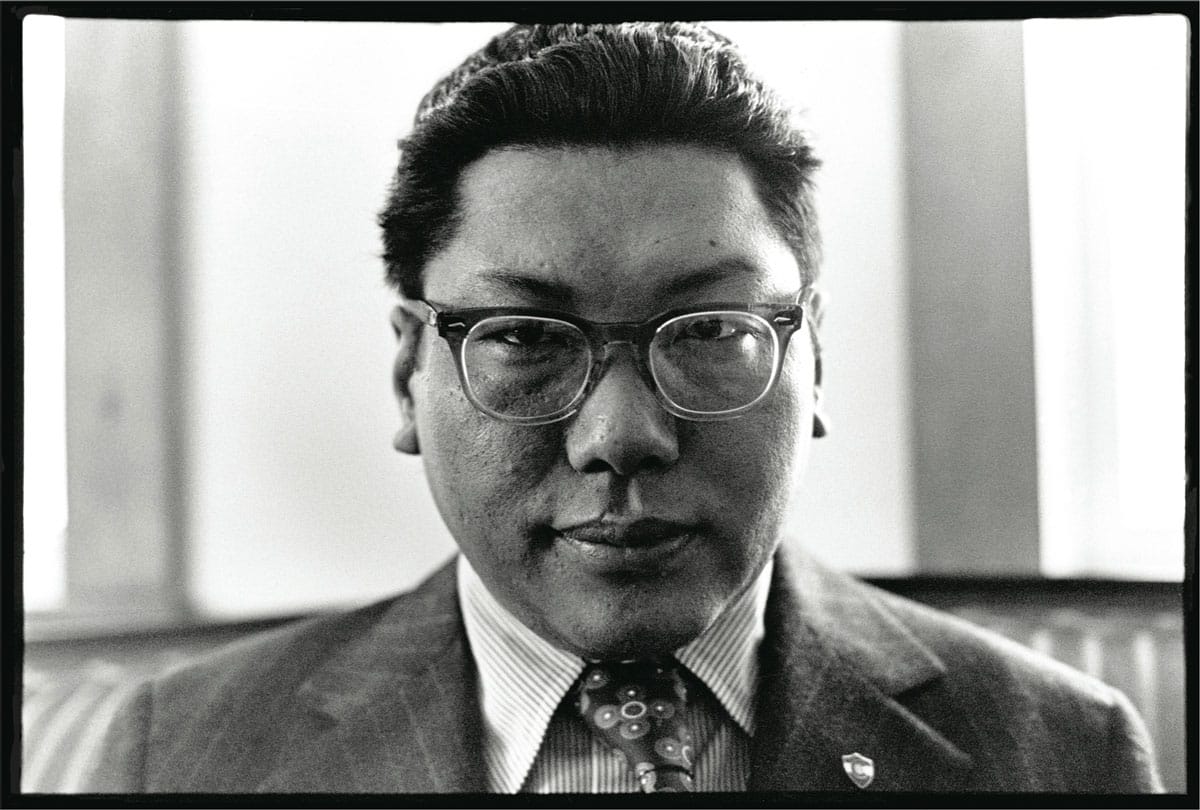

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a seminal figure in twentieth-century Buddhism and founder of this magazine, died on April 4, 1987. Barry Boyce surveys his vast body of teachings and their lasting impact on how Buddhism is understood and practiced.

1. Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism

In the summer of 1968, a twenty-nine-year-old Tibetan monk traveled from Scotland to Bhutan to do a retreat in a small and dank cave on a high precipice—a place where Padmasambhava, who brought Buddhism to Tibet, had practiced 1,200 years earlier. He brought along with him one of his small cadre of Western students. For the student, it was an exotic journey filled with hardships, including ingesting chilies no Englishman should be asked to eat. For the monk, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, it was challenging in a different way. He felt imprisoned by his circumstances. He’d been trained since age five in a rigorous system of study and meditative practice—intended as a direct path to the Buddha’s realization. It had passed from teacher to student in an unbroken lineage for more than a thousand years. He longed to share that training and understanding but couldn’t quite see how—in his new home the buddhadharma was a foreign plaything, either intellectualized or romanticized.

In 1959, when he was nineteen, he had fled Tibet, leaving behind the teachers who had trained him, the monasteries he’d been responsible for, and a society in which his role had been clear. After a few years in India, he’d traveled to Britain to study at Oxford and eventually established a small center in the Scottish countryside. In monk’s robes in this adopted home, he often felt he was treated like a piece of Asian statuary uprooted from its sacred context and set on display in the British Museum. Few Tibetan colleagues offered support, seeming to feel Westerners were sweet but uncivilized and incapable of training in genuine dharma. Deep in his heart, he felt it must be otherwise. What to do?

In later years, Trungpa Rinpoche counseled students faced with daunting circumstances not to drive themselves into “the high wall of insanity,” pushing for answers that may not be ready to appear. Instead, he advised, allow the uncertainty of those pivotal moments to unfold completely and rely on one’s meditative discipline to keep one on the ground, just as the Buddha had done when he famously touched the earth just prior to his enlightenment. In the cave at Taktsang, Trungpa Rinpoche let the uncertainty build and build. And a breakthrough occurred.

With great clarity, he saw that the obstacle to a flowering of the Buddha’s teaching and practice in the modern world was not simply better cross-cultural communication. It was materialism. Not the focus on material wealth alone, but a subtler, deeper form of comfort: “spiritual materialism.” He coined this term to describe the desire for a spiritual path that led you to become something, to attain a state you could be proud of, instead of a path that unmasked your self-deception. The conviction dawned that if people could see spiritual materialism and cut through it, they would find the genuine spiritual path, and it would be fulfilling on the spot. The path itself would be the goal. He left retreat intent on finding students willing to make this journey with him.

In the cave at Taktsang, Trungpa Rinpoche let the uncertainty build and build. And a breakthrough occurred.

As a result of this breakthrough, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche went on to become a dharma pioneer. He lived up to the name Chögyam, “Ocean of Dharma,” and left behind a voluminous and varied corpus of teachings. Right now, you can download eight volumes of his Collected Works to an iPad or Kindle, some 4,500 pages, covering all manner of Buddhist practice, history, art, education, poetry, theater, war, and politics. There are other published books waiting to form future volumes of the Collected Works and more than a hundred potential books to be created from transcripts of his teachings between his arrival in America in 1970 and his death in 1987. He is the author of a small shelf of seminal bestsellers that have shaped how the West understands dharma, such as Meditation in Action, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, The Myth of Freedom, Journey Without Goal, and Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior. His archive is a treasury of calligraphy, painting, photography, and film, as well as audio and video of many teaching events. Here we will dip our toe into this ocean.

There are many stories of Trungpa Rinpoche’s life, but focusing there can mislead. You may conclude “you had to be there.” In fact, no one can claim to have been there for more than a modest slice of the amazing amount of teaching he packed into his forty-eight years. He lived to leave a legacy, so that far into the future people could experience the dharma he taught not as an artifact of a past time and place, but always as “fresh-baked bread.”

2. The Charnel Ground

A Vajrayana, or tantric, master, Trungpa Rinpoche was at pains to dispel wrong-headed notions about the exoticism of tantra. He didn’t shy away from graphic tantric imagery but emphasized the perspective the imagery embodied. He presented it as a subtle and elaborate picture of what our mind experiences. The tantric perspective is potently conveyed in a practice text that emerged in the mind of Trungpa Rinpoche in the cave at Taktsang: the Sadhana of Mahamudra. For forty years, it has been chanted on new and full moon days in centers he founded and is available to be practiced by dharma students new and old.

As part of this practice, one recites a long description of the “charnel ground.” Since the earliest times, Buddhist practitioners practiced in burial grounds, surrounded by powerful reminders of life’s impermanence. Eschewing philosophical statements about “impermanence,” tantra suggests our life is in fact a charnel ground. More than a burial ground, as Rinpoche described it, it is an environment where “birth, life, and death take place. It is a place to die and a place to be born, equally, at the same time.”

Our perspective on life tends to be choosy, he pointed out. We project a partial reality to suit ourselves, but the perspective of tantra takes in the whole picture. We would like things to be just one way—comfortable for us and never-ending—but there are unsettling dichotomies all over the place: As soon as we are born, we are starting to die. Whenever we’re happy, there is a tinge of sadness. We long to be united, but we know we are alone.

We feel wretched, he observed. There is so much wrong with us. And at the same time, we are glorious. We are the buddhas of the future. In some sense, we are buddhas right now.

If we can find the bravery to face the totality of our circumstances— the negativity as well as the richness—a world of invigorating energy will reveal itself. The dichotomies begin to resolve themselves because we stop trying to ally ourselves with one smaller perspective or the other. For example, he taught, if we rely too heavily on our intellect to sort things out, we ignore our emotions. And if we give full throttle to our emotions, we lose our insight. What the tantric view and training can teach us to do, he said, is to “bring together emotion and insight. Insight becomes more emotional and emotion becomes more insightful.” We can exercise control and relaxation simultaneously, he said.

Such a vision would find appeal among young spiritual seekers in the West, who had become disillusioned with what society and traditional forms of religious practice offered. To be told you’re both completely wretched and glorious rang true. It meant you weren’t crazy for feeling bad and good at the same time. He proclaimed to his students that it was not only okay but wonderful to be in a place of simultaneous birth and death, celebration and mourning, and that in fact buddhahood was not some faraway place. It existed in the middle of the charnel ground, where the places we usually run from could be fertile ground for discovery, where, as it says in the Sadhana of Mahamudra:

Whatever you see partakes of the nature of that wisdom which transcends past, present, and future. From here came the buddhas of the past; here live the buddhas of the present; this is the primeval ground from which the buddhas of the future will come.

3. Just Sit…Then Sit More

Within two years of his revelatory retreat in Bhutan, Trungpa Rinpoche found himself in America. A farmhouse, barn, and surrounding acreage in northern Vermont that was soon dotted with retreat cabins became the first home for his teaching and community. He had taken off his robes, married, and settled in among a growing body of students inspired by his honest assessment of the way things were: both the wretchedness and the glory. One seminar after another took place in a tent set up on the front lawn. It was a festival atmosphere befitting the hippie era.

It’s nothing other than what the Buddha himself taught, but Trungpa Rinpoche presented the Buddha’s message in a new vernacular he was discovering.

In addition to the dangers of spiritual materialism, one theme predominated: the centrality of “the sitting practice of meditation.” He was uncompromising. The only way to realize the tantric possibilities described in the Sadhana of Mahamudra — wherein “pain and pleasure alike become ornaments which it is pleasant to wear”—is to sit and to sit and to sit more. When I attended my first seminar as an eager teenage seeker, after a few days we decamped to the town hall/gymnasium for an entire day of sitting meditation. I couldn’t believe it. Soooo boring and claustrophobic. And yet somewhere in there, a little space, a little glory peeked in. The path began.

This foundation undergirds Trungpa Rinpoche’s teachings. If you sit with yourself, with no project other than to follow a simple technique of paying attention, you will gradually familiarize yourself with the texture of mind. Over time, the technique falls away and you’re left with mindfulness of the details of life and awareness of the surrounding space. It’s nothing other than what the Buddha himself taught, but Trungpa Rinpoche presented the Buddha’s message in a new vernacular he was discovering.

As he crisscrossed the country, setting himself up in Boulder, Colorado, and teaching in city upon city, he changed the terms on which dharma had been approached. In an earlier period, Buddhism had been taught as philosophy or religion. He expressed it in terms of its insights about the human mind, borrowing terms from Western psychology and developing fresh ways of translating the Buddhist lexicon. He spoke of ego and egolessness (which the Oxford English Dictionary credits him with coining), neurosis and sanity, conflicting emotions, conditioning, habitual patterns, projection, the phenomenal world, and so on. His teachings intricately described processes of mind more than doctrines. The message was that by becoming familiar with mind in an intimate way, seeing it in the relaxed space of sitting meditation, we meet ourselves fully for the first time.

Rigorous Buddhist practice, as he described it, is scientific and exploratory. We learn what is true— that clinging to an ego is the cause of all our problems— through our own efforts, not because we’ve been told what is true. Because it’s our own discovery, it has more power. He trusted that any human being, regardless of cultural background, can engage in sitting practice fully and attain what the Buddha attained. He was the best-known and most prolific of a body of teachers—such as Ajahn Chah, Mahasi Sayadaw, Suzuki Roshi, Maezumi Roshi, Lama Yeshe, Kalu Rinpoche—who began teaching Westerners in the belief they were equipped to take on the rigors of practice, not just sit on the sidelines with an intellectual appreciation of what the real practitioners were doing. Buddhism in the West was off and sitting.

4. The Soft Spot

One of the dichotomies in Trungpa Rinpoche’s life was his dogs. He had a large dog, a mastiff named Ganesh, and a small dog, a Lhasa Apso named Yumtso, or Yummie. Ganesh intimidated and Yummie ingratiated. Hard and soft. When Yummie toddled along behind Rinpoche on his way into the shrine room to teach, you couldn’t help but laugh and when she jumped onto his lap while he was teaching, it touched your heart—not in some big spiritual way but in the ordinary way we’re all familiar with. Trungpa Rinpoche called that the “soft spot.” We all have it. It can be as simple as a love of ice cream, some way in which we’re human, passionate, vulnerable.

Our soft spot represents embryonic buddhanature. Each of us in our essential nature is a complete, perfect buddha. It may require some uncovering, but as a result of this basic nature, we have a big open heart, or bodhichitta, which he often translated as “awakened heart.”

Trungpa Rinpoche used the soft spot as a jumping off point for teaching Mahayana Buddhism, the path of the bodhisattva. In the mid-seventies, he began to devote considerable attention to these teachings. The foundational path of mindfulness and awareness, in the system he followed, is known as the narrow path, focused on liberating oneself from suffering. The Mahayana is the wide path, focused on liberating others. The Vajrayana is the path of totality that lets one dance with all the energies of the phenomenal world. While they have distinct methodologies, the paths intertwine, and in Rinpoche’s tradition all three are implied at once.

As Trungpa Rinpoche put it, we want to witness our own enlightenment, or more pointedly, ego would like to be present at its own funeral.

At a certain point on the path, we reach the limitation of working solely on ourselves. We’re holding out hope of a final resting place with our name on it. As Trungpa Rinpoche put it, we want to witness our own enlightenment, or more pointedly, ego would like to be present at its own funeral. At this point, it’s necessary to go bigger, to put others before ourselves. We’re now stepping onto the path of compassion, the wide path of the Mahayana, but this brings its own dangers. If compassion becomes a display concocted by ego for its own aggrandizement, we will be back in the trap of spiritual materialism.

Following the classical Buddhist teachings, Trungpa Rinpoche taught that the only way for real compassion to emerge of its own accord is in concert with wisdom. Wisdom in this case means realizing shunyata. This term has long fascinated and confounded philosophically minded students of Buddhism. Western scholars initially described it as the void, as nothingness. The newer term “emptiness” was an improvement, but it could still leave you puzzled. Once again, Rinpoche taught about it experientially:

Shunyata literally means “openness” or “emptiness.” Shunyata is basically understanding nonexistence. When you begin realizing nonexistence, you can afford to be more compassionate, more giving. We realize we are actually nonexistent ourselves. Then we can give. We have lots to gain and nothing to lose at that point.

To present these teachings most thoroughly, Trungpa Rinpoche gave extensive commentary on a classic Mahayana text built around a series of sayings, which he referred to as slogans. (These commentaries are published as the book Training the Mind.) A slogan such as “Be grateful to everyone,” when memorized, can emerge in your mind at an opportune moment—not as some rule you’re struggling to follow but as a sudden catalyst for your soft spot. You find the possibility of putting others before yourself—without having to strategize it.

A key practice to cultivate bodhichitta is tonglen, literally “sending and taking.” You send out warmth and openness to others and you take in their pain and difficulty. This practice, similar to the Theravadan metta practice, became the focus of the books of Pema Chödrön, who learned it from Trungpa Rinpoche. This great switch, where the first thought is of others, is the essence of genuine compassion and a key to real liberation.

5. Art in Everyday Life

Early in his time in America, Trungpa Rinpoche was hailing a cab in New York City. The Beat poet Allen Ginsberg was trying to hail the same cab. They were introduced, and Trungpa Rinpoche, his wife Diana, Ginsberg, and his ailing father shared the cab. After dropping off Ginsberg’s father, they continued to Ginsberg’s apartment, where they stayed up long into the night talking and writing poetry. In the introduction to Volume Seven of the Collected Works (devoted to poetry, art, and theater), editor Carolyn Gimian notes that this chance meeting started a long and fruitful friendship: “On the Buddhist front, Rinpoche was the teacher, Ginsberg the student; on the poetry front, Rinpoche acknowledged how much he had learned from Ginsberg, and Ginsberg also credited Trungpa Rinpoche with considerable influence on his poetry.”

For Trungpa Rinpoche, humor meant not jokiness, but seeing the dichotomies and the totality at once, which allowed one to play—with one’s communication, with one’s perceptions, with one’s gestures. It evinced real freedom.

Rinpoche had received training in Tibetan poetics, where the metrical forms were well established and the topics restricted to the spiritual. Ginsberg was a worldly poet, composing in a freeform style. Yet he shared Rinpoche’s deep appreciation of classical forms, believing that learning strict meter allows one to have good rules to break. Poetry became an arena in which Rinpoche could play, and display a sense of humor. For him, humor meant not jokiness, but seeing the dichotomies and the totality at once, which allowed one to play—with one’s communication, with one’s perceptions, with one’s gestures. It evinced real freedom.

TIMELY RAIN

In the jungles of flaming ego,

May there be cool iceberg of bodhichitta.On the racetrack of bureaucracy,

May there be the walk of an elephant.May the sumptuous castle of arrogance

Be destroyed by vajra confidence.In the garden of gentle sanity,

May you be bombarded by coconuts of wakefulness.

Trungpa Rinpoche saw art and the arts not as diversions to give one relief from the serious side of life, nor as something for an elite who could afford the time and money. He spoke of “art in everyday life,” that life could be lived artfully. Our speech, our movements, our gestures, our craftsmanship, can be carried out with grace, not self-consciously as a performance, but intrinsically as part of our being—and as an outgrowth of meditation. In fact, he felt that art and artistry emerged from the space of meditation:

Beethoven, El Greco, or my most favorite person in music, Mozart — I think they all sat. They actually sat in the sense that their minds became blank before they did what they were doing. Otherwise, they couldn’t possibly do it.

From early on, he played in many realms: film, theater, song, photography, painting, calligraphy, flower arranging. In 1974, he founded the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) as a place where an artistic sensibility could be an integral part of higher education. Education at Naropa, he said, would marry intellect and intuition. As Gimian points out, in the Japanese notion of do, or way—as in chado, the way of tea, or kado, the way of flowers— he saw a model for how secular activities of all kinds could become paths to awakening.

Drawing on formal training in flower arranging, he used it as a means to convey certain principles, such as heaven, earth, and human — with heaven representing open space, earth the ground, and human that which joins the dichotomy. In theater, he created exercises that helped actors engage the space around them, coming to know relaxation by knowing tension. In visual arts, he explored the process of perception, the interplay between the investigating mind that looks and the big mind that sees. These teachings formed the basis for a program called dharma art, which used simple exercises like arranging objects to help students go beyond the limits of perception based on ego’s small reference points. He and a team of students created art installations containing outsized arrangements of natural and constructed objects that could bring on a blanking of the mind. (These can be seen in the film Discovering Elegance.) In the path of dharma art, the worldly and the spiritual completely intermingled, and became in his words “an atomic bomb you carry in your mind.”

6 . Victory Over War

By the mid-seventies, what had begun as a loose association of hippies following a guru evolved into a multifaceted community. People had grown up and taken on families and greater responsibilities. Trungpa Rinpoche had begun to emphasize care in how you dressed and conducted your household. There were simple protocols. For talks, for example, he expected students to sit up and pay attention rather than sprawl about. Senior teachers from Trungpa Rinpoche’s Tibetan lineages were hosted on crosscountry tours. The head of the Kagyu school, His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa, made the first of his three U.S. visits in 1974. It was a monumental affair. Trungpa Rinpoche transformed before his students’ eyes. They saw his great devotion to the Karmapa and to his lineage. He met the Karmapa’s great beaming smile with an equal smile and a bow of respect. We his students wanted whatever they were having.

To warrant devotion and service, a teacher must genuinely embody the teachings. Ultimately, student and teacher effect an eye-level meeting of the minds. Relatively, the student supplicates and serves the teacher. As Trungpa Rinpoche demonstrated how to do this for His Holiness, we learned to do it more for Trungpa Rinpoche. This is how he had learned from his teachers in the longstanding tradition that began in India with the earliest Vajrayana masters. Serving the teacher means helping in the propagation of the dharma and can encompass everything from translation to giving meditation instruction to helping run a household to acting as an appointments secretary. In inviting students to take on serving and attending roles, he made it possible for them to learn the dharma in day-to-day situations, where the rubber meets the road. We discovered that serving the teacher can be a powerful element in the spiritual path, part of the process of wearing down ego and opening the student to teachings that challenge cherished habits and views.

One form of this practice as service was called the Dorje Kasung, which roughly translated means those who protect the teachings and help make them accessible. The kasung could help the teacher create a good container in which the teachings can be heard and experienced. A meditation hall that is clean and quiet and well lit and ventilated provides an excellent container for mindfulness practice and to hear teachings. Likewise, if someone sits at the gate in an upright posture looking out as a reminder to students to enter attentively—and make a transition from the speed of daily life—they’ll be inspired to hear the teachings, take them to heart, and wake up.

Those of us who joined the Dorje Kasung dressed in simple uniforms and our role was well known to students. One might sit for long hours doing almost nothing outside a meditation hall, acting as a kind of gatekeeper, just as in the temples of old. We provided information and direction to those who entered the center for the first time. We were also there in the event of emergency, such as a power outage or fire or theft. Students began to feel the kasung helped ensure a safe, calm atmosphere for practice and study, a good container.

Rinpoche had taught meditation and meditation-in-action, and now he taught meditation-in-interaction. He gave seminars especially for the Dorje Kasung, which inculcated in us certain principles, such as gentleness, putting others first, and fearless action in the midst of chaotic situations. The teachings were often expressed in metaphors that one could unravel and unpack in those long hours looking at a rug and a dog in the entryway to the teacher’s residence:

If there are lots of clouds in front of the sun, your duty is to create wind so that clouds can be removed and the clear sun can shine.

The training often focused on how our minds respond to threat. The discipline, which proved valuable in many facets of life, honed your ability to remain alert and spacious at the same time. It encouraged you to learn how to “be like a mountain” amid provocative and even threatening situations—with gentleness and precision, not creating a big scene. You were exhorted to become a “warrior without anger.”

This was monasticism with an edge — it would push deep buttons.

Trungpa Rinpoche decided to take this training to a higher level. He instituted an annual encampment, which followed militarylike protocols. People spent ten days living in tents, dressed in uniforms, and drilled — a form of moving meditation in the way he approached it. In its ritualized schedule, self-sufficiency, direct experience of the elements, regular practice of meditative activities, and sameness of dress, it was a Western form of monasticism, he said.

It was monasticism with an edge — it would push deep buttons. We engaged in a mock skirmish, a version of capture the flag. There was uproarious humor, but we boys and girls were also shocked and humbled to find the aggression and anger that could emerge in our minds while playing a mere child’s game.

From this practice program came the motto for the whole Dorje Kasung: Victory over War. In essence, he was teaching us how war could be cut off at its origin. Conflicts test the mettle of our awareness. If our discipline doesn’t prepare us to face them, we will revert to deep-seated negative patterns and create great destruction. This is how war is born. It’s killing people all the time. It’s killing them now. This form of meditation-in-interaction that encouraged people in the midst of challenging situations to manifest with gentleness and humor—rather than anger and fear—carried implications for seemingly insurmountable challenges we face in the world at large.

7. Enlightened Society

In 1976, eight years had passed since the pivotal moment in Bhutan when he saw a way to bring dharma to the West. In that short period, he had taught hundreds of seminars, initiated many hundreds of students into advanced Vajrayana practices, founded an array of institutions and meditation centers, and infiltrated the dharma into unfamiliar territory like avant-garde theater and Beat poetry. Now, another pregnant pause emerged.

The Sadhana of Mahamudra was a kind of revealed text known as terma. Traditionally, terma can emerge as a whole in the mind of a great practitioner. They’re not regarded as the teacher’s personal work, and special marks are put on the text to indicate that. In being revealed, they transcend the personality and ownership of the teacher who receives them. They have an inherently egoless quality, you might say. They are also timely.

In the fall of 1976, Trungpa Rinpoche began to discover more terma. These spoke to a form of teaching that was not strictly Buddhist. They became the basis for Shambhala training, which Rinpoche intended as a secular means of mind training. He called it a path of warriorship. Warrior in this case referred not to someone who fought to gain territory, but rather someone who was brave, who was willing to work with their fear. On the path of the warrior, you work with your fear not by pushing it down, but by “leaning into it.” At that point, he taught, you discover fearlessness, which is not the absence of fear, but the ability to ride its energy.

The breakthrough he had during this period occurred on several levels. For one thing, Rinpoche stepped back from his intense schedule to take a year’s retreat. When he emerged, he began to exhort his students to “cheer up!” He felt their practice of Buddhism had become stuck in many respects in earnest plodding and a habit of looking inward, both personally and as a community. Though many strongly resisted at first, the warrior teachings of Shambhala offered larger possibilities of opening up, in the form of a great societal vision:

Shambhala vision applies to people of any faith, not just people who believe in Buddhism. Anyone can benefit without its undermining their faith or their relationship with their minister, their priest, their bishop, their pope, whatever religious leaders they may follow. The Shambhala vision does not distinguish a Buddhist from a Catholic, a Protestant, a Jew, a Muslim, a Hindu. That’s why we called it the Shambhala Kingdom. A kingdom should have lots of different spiritual disciplines in it.

What he called kingdom here, he also referred to as enlightened society, where each person could realize they possessed basic goodness. Through group sitting practice married with contemplation of the warrior principles of fearlessness and gentleness, Shambhala training was designed to instill an appreciation of basic goodness in all its dimensions. If such seeds are planted one by one, our society could become an enlightened one.

As with the Sadhana of Mahamudra and dharma art, the power of the Shambhala teachings lay not in an imposing ideology but in a direct perception of the world, described in this context as “discovering magic,” experiencing a quality known in Tibetan as drala:

Drala could almost be called an entity. It is not quite on the level of a god or gods, but it is an individual strength that does exist. Therefore, we not only speak of drala principle, but we speak of meeting the “dralas.” The dralas are anything that connects you with the elemental quality of reality, anything that reminds you of the depth of perception.

8. Such Thunderstorm

The late seventies and the eighties saw tremendous deepening and maturation of the teachings and institutions Trungpa Rinpoche laid down. He presented the most refined levels of what he had been taught and had discovered. At times, these teachings could be hard to fathom, but he provided commentary so future generations could follow the footprints and see for themselves what they might reveal. By the end of his life, he had personally conducted thirteen Vajradhatu Seminaries, three-month training programs in the yana of individual liberation, Mahayana, and Vajrayana teachings. Rigorous periods of all-day practice and study alternated in a way that had no precedent in the traditional training regimens Trungpa Rinpoche learned under. He told some it was his greatest achievement.

In 1987, he died. And we had to let go. His death was commemorated with great pageantry in a high meadow on the Vermont land where his journey in America had begun. Thousands paid tribute. Prominent Tibetan teachers, Zen masters, and other Buddhist teachers he had influenced, artists, poets, and politicians joined students who had walked the many paths he introduced. It was sad, and yet joyful. He left all of himself for all to see. Many more people in the future will derive benefit from his teaching than those who knew him in his lifetime. In his will, he left these parting words:

Born a monk, died a king.

Such thunderstorm does not stop.

We will be haunting you along with the dralas.

Jolly good luck!