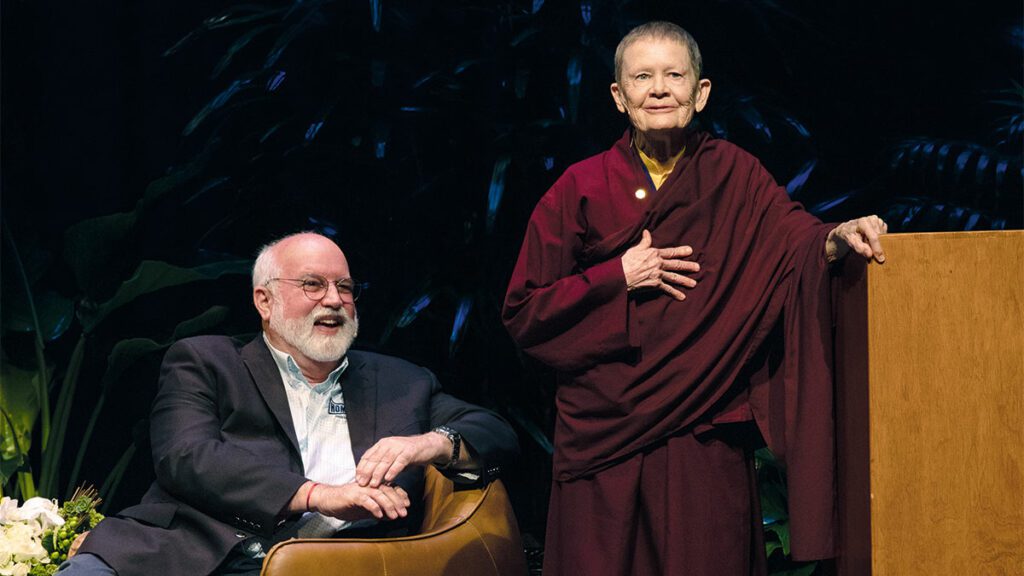

Pema Chödrön: There’s an ideal in the Buddhist teachings called the bodhisattva. Bodhisattvas are people whose purpose in life is to alleviate suffering. The main thing they want to do is soothe the sorrows of the world. I’m sure that Father Gregory does not like to be called a bodhisattva or anything like that, but as far as I’m concerned that’s what he is.

I came to know of Father Gregory’s work and Homeboy Industries from his wonderful, touching book Tattoos on the Heart. Sometimes it makes you cry because the stories are so deeply moving, and sometimes you laugh out loud because Father Gregory has a very good sense of humor. Now, I was raised Catholic, so I have trouble calling him anything but Father Gregory, but he has asked me to call him Greg, so I’m going to try.

When someone like Greg is willing to put themselves out there and dedicates their whole life to benefiting other people, that’s a modern-day bodhisattva. The compassionate bodhisattvas alleviate suffering at different levels. At the outer level, that means helping people who suffer from hunger, thirst, violence, and neglect, who have no place to live or are not able to get a job. Bodhisattvas want to alleviate these outer circumstances that cause people to suffer greatly. The main way Homeboy Industries does that is by providing jobs. A couple of its mottos are “Jobs, not jail,” and “Nothing stops a bullet like a job.”

They say the bodhisattvas are also interested in alleviating suffering at the inner level. That inner level suffering comes from feeling that you’re really not okay, that nobody could love you. That comes from feeling there’s something fundamentally wrong with you, fundamentally lacking in you. This kind of suffering is all-pervasive—so many of us feel in the core of our being that we’re not okay.

This inner suffering is addressed at Homeboy by being such a loving community. So many of the stories in Greg’s books, Tattoos on the Heart and Barking to the Choir, are about people who’ve never felt loved in their lives. Then, through this loving community, people who’ve never felt that they were worth anything know that they are worth something. They know they are worthy of love.

Finally, there’s a third level of suffering, which is sometimes considered the most profound of all. That’s the suffering that comes from having a closed mind and a hard heart. It’s the suffering that comes from feeling that some people are important and other people just don’t count, that “this group is okay and that group is not okay.”

This closed-mindedness and hard-heartedness is a very deep kind of suffering. This kind of mind is actually getting a lot of press right now because of what’s happening at our borders. I don’t know if it’s fair to say that it’s indifference to suffering, but it’s not being able to have an empathetic feeling, a feeling of kinship, with people whose lives are so desperate that they’re trying to get into the United States for a better and safer life.

The way Homeboy addresses this kind of mind is very interesting. One of the ways is to have people who were formerly enemies, like members of rival gangs who would have happily shot each other, work together side by side. When people get to know each other, that cuts through the closed-mindedness and hard-heartedness.

It’s not easy to create situations in which something softens up in a hard heart or opens up in a closed mind, but if a lot of people knew how to do that, can you imagine what kind of world this would be like? What a great place it would be! That would be peace on Earth, you know.

I’m very impressed with the bodhisattva activity of Homeboy Industries. It’s a whole community of people who are committed to alleviating suffering and the causes of suffering. I think that’s all I want to say, except, “Three cheers for Homeboy Industries!”

Father Greg Boyle: I think what Pema is expressing is our dream. What would it look like if we cultivated a community of kinship such that God, in fact, might recognize it? How can we imagine a circle of compassion with no one standing outside it?

It’s about going out to the margins, because that’s how the margins get erased. It’s about standing with the poor and the powerless and the voiceless. You stand with the easily despised and the readily left out. You stand with the demonized so the demonizing will stop, because demonizing is always untruth. You stand with the disposable so the day will come when we stop throwing people away. And you imagine something different; you dream of something different. That’s what Pema’s teachings have shown me for many years, even before I met her.

A lot of Buddhist texts start with these sweet words: “Oh nobly born, remember who you really are.” I think that’s what happens at Homeboy. You remember who you really are.

This morning, I got a text message from Dennis, one of our workers. He said, “They may have to cut off half of my tongue.” Someone had shot at him. They missed but it caused a car accident and he bit into his tongue. He said, “My tongue isn’t healing, they’re going to have to cut it off.”

“Here’s the truth: You are exactly what God had in mind when God made you, oh nobly born.” -Father Gregory Boyle

I texted him back and said, “Dennis, my magnificent son. Oh nobly born, remember who you really are. You are this light and fountain of unconditional love. You are courage, you are dignified and noble. You are thoroughly and unshakably good. You are not your tongue.”

We receive the tender glance of God, and then we’re compelled to be the tender glance in the world. We breathe in the spirit that delights in our being and then we exhale it. (Exhales) All of us are called to be enlightened witnesses. Through our kindness and tenderness and focused intent of love, we help people return to themselves.

At Homeboy, we’re kind of allergic to the notion of holding the bar up and asking homies to measure up. I don’t think our God ever does that, so why would we? Instead, we hold the mirror up and tell people the truth, knowing that your truth is my truth and my truth is a gang member’s truth. It’s all the same truth.

Here’s the truth. You are exactly what God had in mind when God made you, oh nobly born.

When people become that truth, when they inhabit that truth, no bullet can pierce it. No four prison walls can keep it out and death can’t touch it. This is a huge thing—to know and remember who you really are, anchored in love, tethered to a sustaining God, and not even the least bit shaky in your own unshakable goodness.

The Acts of the Apostles says, “And awe came upon everyone.” That suggests the measure of health may well reside in our ability to stand in awe at what the poor have to carry, rather than in judgement at how they carry it. I stole that from Pema, by the way. (Laughter) I’ve been using it all these years. That’s kind of a confession.

Homies try to make friends with their wounds, because if they don’t, like all of us, they get tempted to despise the wounded. The hope is that we can, in exquisite mutuality, look at each other and with breathless delight say, “You’re here.” Then the only response is to say, “You’re here.” And right there is kinship.

After one of our homies was killed in a random shooting, the question I was asked most by his friends was a good one: “What’s the point of doing good if that can happen to you?”

I thought it was a good question, worthy of an answer. I stood in front of the packed church at his funeral and I said, “Here’s the point. Before he left us, he knew the truth of who he was. That he was exactly what God had in mind. ‘Oh nobly born’ was he. He remembered, in a community of tenderness, who he really was. No bullet can pierce that: death can’t touch it. For it’s a lie that talk of God doesn’t comfort you. You’re here.”

Question from moderator Jose Arellano: Because we’re talking about spirituality, what is your take on God? (Laughter) I’m just saying.

Pema Chödrön: The God language actually makes me uncomfortable. That’s interesting, since I talk so much about being comfortable with uncomfortableness. (Laughter) I’m sitting here sort of thinking, “Oh God, I wish he’d stop talking about God quite so much.” (Laughter) Then I’m thinking, “Well, work with it, Pema.” (Laughter)

I resonate so much with your message, Greg. I just don’t call it “God.” I call it “uncovering what is basic and good in humanity.” My problem with the word “God” is that it sounds like it’s something other than us. Do you think of it as something other?

Father Greg Boyle: No.

Pema Chödrön: But to me, the word “God” always indicates that there’s something other. It’s like “father figure,” or something like that, which is where my discomfort comes from. I don’t mean to be harsh, but there’s no point pretending otherwise. (Laughs) I do think that language gets in the way a lot.

Father Greg Boyle: Well, because there are a few people who believe in God (Laughter), I always want to call them to a fuller sense of God. I think we’ve settle for a puny God, a partial God, which has nothing to do with the God we actually have.

After Dylan Roof killed all those people in the Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston—and I’ve heard you speak about this, Pema—family members stood in front of him and said, “We forgive you.” Now, part of my way of talking about God is to say that that is the God we actually have.

Pema Chödrön: The people who said, “We forgive you.”

Father Greg Boyle: Yes, that “we forgive you,” with a great reservoir of love. Then when Roof was sentenced to be executed, people called it God’s justice. That’s the God we’ve settled for—the partial God. But that’s not the God we actually have. St. Ignatius of Loyola talks about the God that’s always greater. For those of us who use the language of God, it’s important to always remember that.

Believing in people’s innate goodness, what I would call the unshakable goodness in every person, is so important right now, especially when you’re dealing with gang members. When we get to the place in our society where people demonize members of the MS-13 gang as “animals,” I would say that’s the opposite of who God is. That’s the opposite of the truth. People say, “Some people are just evil,” they divide people into “good guys” and “bad guys,” but I don’t buy that in any sense.

Pema Chödrön: No, I don’t buy it either. That demonizing language comes out of some kind of deep hurt. If it’s our basic nature to have an open mind and a warm heart, then a closed mind and hard heart is the greatest suffering of all, because it covers over our basic nature. That’s why the bodhisattva wants to remove the suffering that comes from demonizing others.

I imagine there are lots of people whose minds were polarized and closed who have changed their views because of what happens at Homeboy. I think that’s amazing, because you can help people meet their basic needs much more easily than you can change hearts.

Moderator Jose Arellano: What is the most important thing to each of you?

Pema Chödrön: For both of us, it’s alleviating suffering, wouldn’t you say?

Father Greg Boyle: Yeah.

Pema Chödrön: I’ve always had a place in me that thinks, “Oh, I wish I had actually been able to alleviate suffering the way you do, Greg.” (Indicating Father Boyle) You know, in the trenches, where I could really get my hands dirty. Instead, I travel around in kind of a little bubble. It’s gratifying when people tell me my books have helped them—I don’t want to put down what I do—but I so admire the level of bodhisattva activity you do.

Father Greg Boyle: Well, what feeds that work is what I call extravagant tenderness. “Tenderness” is so rich a word. We always say at Homeboy that if love is the answer, community is the context and tenderness is the methodology.

“At Homeboy, people who never felt that they were worth anything know they are worthy of love.” -Pema Chödrön

At Homeboy, our experience is that suffering gets alleviated in community with extravagant tenderness. Tenderness becomes the connective tissue, as opposed to, “I love you.” Somehow, tenderness is where you meet people. It becomes exquisitely mutual, where I’m not saving you, I’m not even serving you, I’m allowing, or trying, to be reached by you. Then it becomes mutual and life-giving. I find tenderness is sort of a thing for me right now.

Pema Chödrön: It’s a much better word than “love.” “Love” is so loaded it almost doesn’t touch you, whereas “tenderness” actually does.

Moderator Jose Arellano: Where does that deep desire to relieve suffering come from for each of you? What is the root of it?

Father Greg Boyle: It’s about joy. I feel like the most selfish person I know, because if your job is to alleviate suffering, that’s where the joy is. That’s why I’m at Homeboy Industries, not because it’s a tough job and “somebody’s got to do it.” It’s about joy, about delight, and about showing up. People are hilarious and people are heartbreaking and people are so vulnerable and so trusting that it’s joyful. William Carlos Williams used to say about poetry, “If it ain’t a pleasure, it ain’t a poem.” That’s sort of what Homeboy is about. That’s the secret. People think relieving suffering has to be a grim duty, but it isn’t. It’s joy.

Pema Chödrön: I really resonate with that answer. It brings me so much joy.