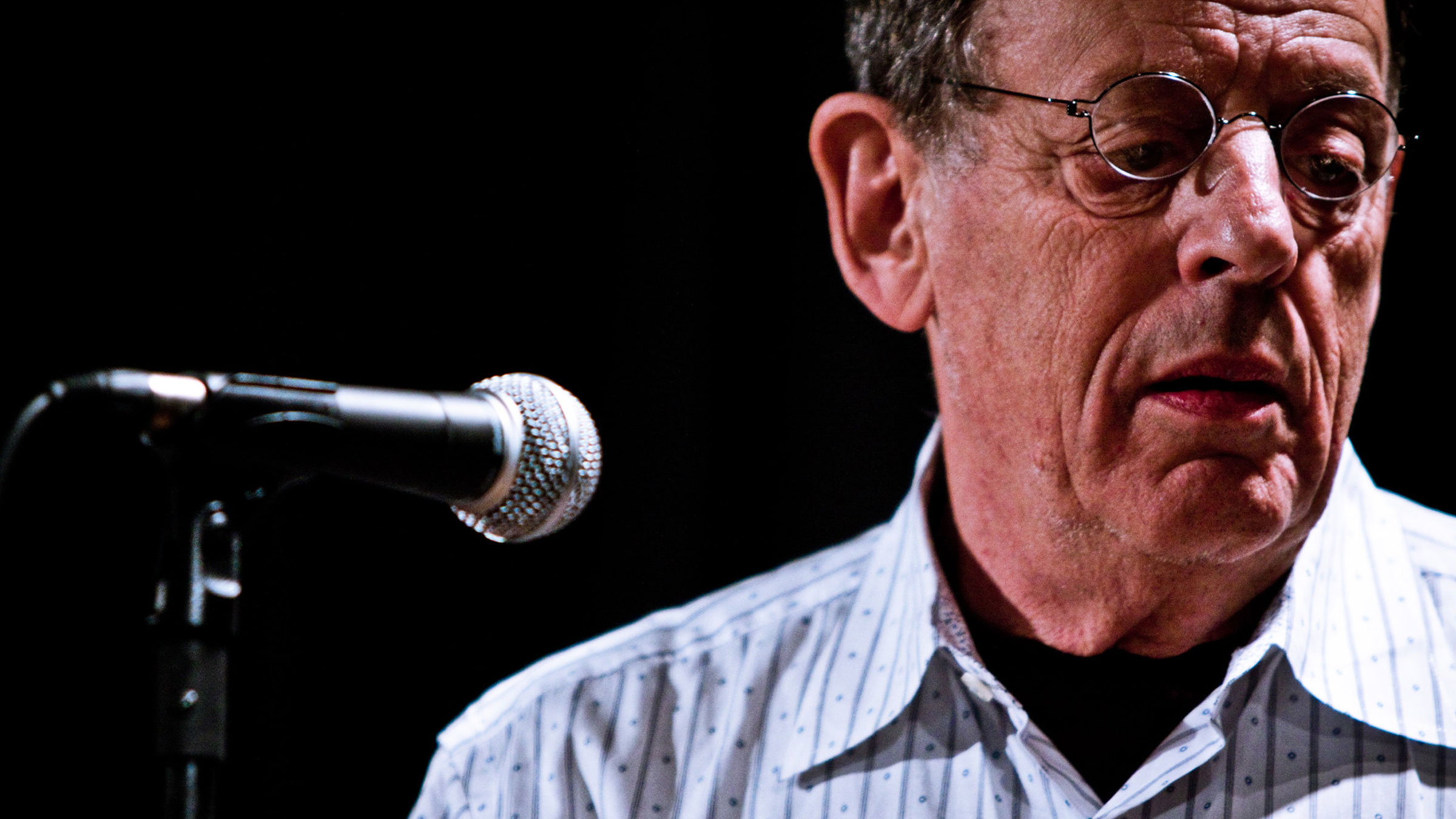

I arranged the microphone and tape recorder on the wooden table in Philip’s kitchen in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and then I sat back to enjoy an hour alone with one of our era’s premier musical artists, and a generous portion of his pasta and sauce. But I did little else: I provided him a good reason to talk out loud, and the tape recorder captured his words. It was intimate and yet it was also public.

Later, editing the transcript of that hour’s torrent of words, I was struck by how Philip really conducted his own interview—stopping himself in midstream, asking himself questions to redirect the flow, and so on, managing to fill up that hour with little help from me. The actual interview took shape through his own questions to himself, so why not leave them that way, as if he had written a piece for two pianos, and could play both at the same time for us? —Stephen Brooks

What is this interview going to be about?

Not so much about writing music, but about playing music—the activity of performance, and the “three times”: past, present and future.

I’ve always considered writing and playing connected. When I have an idea about a piece, the cycle of activity is to have an idea…

hopefully have an idea.

…then I write the piece and then perform it. So playing in public completes the cycle of creativity. I do about sixty or seventy concerts a year so there’s a constant activity of playing. The thing that interests me is what happens when I am playing, I mean, in front of hundreds of people or sometimes thousands of people. The whole encounter with the audience is an interesting one.

It points out, I think, what music-making is all about. If you write music and are deprived of that encounter, there’s a tendency, perhaps, to lose sight of the relationship with other people. The question came up among composers in the sixties and seventies about what the role of the composer was. What is the function of the composer in the world that we live in?

“Performance is not an activity that happens in isolation. It really happens in relationship to people. This of course is a very good dharmic point, the idea of dedicating your work.”

I remember in the sixties there were a lot of people who had very political views. They were Europeans, mainly, but there were some Americans as well. They felt that their music had to involve society in a political way. They espoused various left-type ideologies and tried to make their music work in a political way. Very often these people were writing fairly abstract art music, and it was hard to make it fit into a populist view. That was quite a problem: you had this contradiction that these people talked about writing music for the people, but their music was music that no one wanted to listen to.

As I began playing more, I began to see that instead of this abstract idea of the relationship of the composer to the people, an encounter with the audience is happening all the time when you’re actually playing the music. Then I began to become aware of my own, let’s say, psychological or emotional mental processes while I was playing the music, and I began to ask myself various questions. The first question was about the relationship with an audience.

That’s an interesting one.

I found that when I went on the stage and the piano was there and I sat down, there was, of course, a certain excitement about it. But I always felt that I was in the right place—that I was in the right place and that they were in the right place (laughs), if you know what I mean.

That doesn’t mean that I don’t sometimes get nervous. But I know people who even take drugs sometimes, tranquilizers, to quiet the stress. You’d be surprised. To me that is totally counterproductive because it blunts the experience. To me the intensity of the experience is what you want to take in, in a certain way.

This situation—one person in front of several thousand—is peculiar. I mean, most of the time we don’t live that way. We pass people in the street or we have encounters like this one. But to be a performer—there’s something interesting about it. It has a very specific role: it has a social history, it has an artistic history, it has a cultural history.

I began to perform at a very early age, when I was only ten. I was originally a flutist, playing in orchestras, and I was on television programs and stuff like that. So I can say that at this point I’ve been playing in front of people for fifty years. I think that accounts for the fact that it seems a very natural place for me to be, when I say I’m in the right place and they’re in the right place. I think it really has to do with my own personal history.

The second thing that I began to ask myself was, how do you remember what you’re playing? Well, it’s all memorized, so to speak. When I say I do sixty or seventy concerts a year, what I usually do is I learn a program and I play it all year. I’m not an improviser, so I don’t go out on stage and make something up. I’m basically playing set pieces that I know.

Even so, how do you know what to play? How does the mind do that?

I began to study my own performances to try to figure that out. I’m playing six or seven or eight minutes, and each note flows into the other note the way I composed it. I guess a simple answer would be, well, I memorize it, but that rather begs the question.

The question is, how does the memory come to you? How do you evoke memory? How does the finger know which note to go to?

First of all, there is a kind of mechanical memory. If you’ve forgotten how something goes, you might go back a few phrases and take a running start and get through it. You’ve probably done that with things you’ve memorized. But the mechanical memory is probably not dependable enough to do an evening-length concert. I don’t think it would even be possible.

So I began to get down to the moment—to try to dissect the actual moment before I play the next note. Let’s say I’m playing a melody and there are five notes in all, and I’ve played three notes and I’m about to play the fourth note.

The question is: where does that fourth note come from?

This is really a good question. It’s a funny question.

It seemed to me that I was hearing it. I could hear the note and then I was playing it. I’d hear the next note and I’d play it. In this case memory had to do with hearing. I had to hear something that was going to happen. This is the first of the “three times.” This is the future time. Right?

At the same time it’s an exquisite moment because I’m completely in the present. In fact, one of the functions of the audience for me is that it intensifies the feeling of being in the present. It’s very hard to get beyond simplistic descriptions of it. The moment itself tends to be poetic. It seems to be beyond…you have this intense feeling of being present in front of the audience at that moment.

What I do is that I can remember the music I just played, I can hear the notes I’m about to play, and I’m caught in this moment in between. It’s almost like that paradox of a Greek philosopher: how do you reach a place if you go halfway at a time? How do you ever reach the final destination? It becomes logically impossible.

Of course, the difficulty with the problem is the way it’s described. Actually we don’t have any problem at all reaching the other side. The problem, usually, is that the way we describe it makes it a problem. Moving, we simply carry the present with us from moment to moment. That’s really what happens.

So that future moment, that note we are about to play, is the next moment. And the moment that we just played is always the past moment. This is like a nucleus that we carry with us, which includes the past, the present and the future. We are always carrying it with us. At least in the experience of playing music that’s what happens, I think.

It’s interesting because it’s still possible to forget, you know. That’s another question: how is it that we don’t remember?

Memory is only an aid to the creativity of playing. Memory isn’t actually playing. When I say I can hear the next note, I’m hearing it in my memory. So memory actually is just an aid. It allows us to project into the next note based on what we’ve heard in the past, and, as I said, being locked in the present in a way. Actually I think that’s bad wording, because when you say “locked in the present,” it seems to say there’s a problem to solve. Actually there isn’t any problem because it’s a completely fluid moment. It’s constantly moving: the future note is always one note away from you and the past note is always one note behind you (laughs). It’s cute, isn’t it?

That brings up another question: how can you play the same concert seventy times?

Well, you don’t play the same concert seventy times. The only way you can have an interesting performance is to be interested in what you’re doing. Clearly, if you’re just mechanically playing something, it’s going to sound that way and no one is going to be very interested.

A friend of mine said that the craft of performance is playing each piece each time as if its new.

Each time you play it, it becomes new. This is one way I’ve been thinking about memory and the present, past and future times all fitting together. I called it an exquisite moment. It’s an exquisite moment because the audience and the situation of performing allows us, requires us, to think of that moment. Very often we go through life without thinking about that moment. We talk about mindfulness but we’re not very mindful, most of us. Mindfulness is something that we can do as a special activity maybe, but being mindful all the time is very difficult to do.

What about the audience?

The activity of listening is a little different. The body, speech and mind are together when you’re performing. The body is literally the body that plays. The speech is the text, the music that we do. The mind is what allows us to connect the speech and body in this case. So the three become very integrated.

When we listen we don’t have that gift. Listening in itself may not be complete, because, as you know, people go to sleep during performances. They think about laundry lists or whatever. Keeping the mind focused is not something we’re required to do. We often don’t. Being a good listener is probably more difficult than being a good performer. Being a good performer is easier because if you aren’t a good performer you find out right away; it’s self-corrective in a way. If you’re not a good performer you don’t get to do it very much. No one asks you to do it. Nor would you want to do it. The exquisite moment could become a very painful moment.

That brings up a good question. Who is the audience? Who is it that we’re playing for?

The answer of course is that you’re the audience. This is the curious thing: that the first person who hears the music will be you, the author of the music. There was a composer named Carl Ruggles who lived in New England and died some years ago. He was a kind of a maverick composer, didn’t belong to any particular school, kind of like Charles Ives. He said that when he wrote a chord he would play the chord ten thousand times. And if he still liked it after ten thousand times, he thought it was good. Then he would write it down. I mean, it’s a rather hard way to do it (laughs).

But that’s an interesting thing that he’s talking about.

What he’s talking about is his testing the music and using himself as the listener. I am the composer; I also am the listener. Is it happening for me? If it isn’t happening for me there’s obviously no point in writing it down.

When I finished “Satyagraha,” I could sit down and probably play most of the opera on the piano. I could play it for my colleagues, the writer, the designer, the director. We knew what the piece was. But then something else happened. The first night there was an audience present, the whole thing changed. You think you know the piece. You think you know what you’ve done, but you’re sitting in the hall and you look out and suddenly there are 1500 people there and you no longer know it. And you’re asking yourself the question, the very same question: are people going to like it? What are they going to hear? Are they not going to like it?

Well, clearly, you wouldn’t be there if you didn’t like it.

You’ve had plenty of opportunity to make whatever corrections you wanted to make, to get the piece the way you wanted. Still the question comes up: is anyone else going to like it? The first audience is yourself and, the second audience will happen the first night. And between those two there’s an uncatchable moment that is about to pass. Once it has been heard by somebody else you will no longer ever be able to hear it the same. I don’t know if anyone has remarked on that, but I can tell you my experience is that you will never hear the piece the same way again.

We’re coming back to the idea of the audience and the function of the composer.

Performance is not an activity that happens in isolation. It really happens in relationship to people. This of course is a very good dharmic point, the idea of dedicating your work. One of my teachers told me that the best dedication was music.

Dedicating merit?

Yes, exactly. It’s almost the best thing an artist can do. Artists are lucky because they have work that they can dedicate. Well, we all do, everyone does, but the artist has something very tangible that underlines the relationship to the public, to the audience. It’s not something that we’re doing for our own enlightenment, so to speak. I mean, we’re not doing it, as my father would say, for our own amazement. He liked to change the word amusement to amazement. Instead, we’re doing it with the awareness of the impact that all these others, the public, have on the work, and vice versa. It’s the idea that we don’t do work without the others. The others are there. In a real sense we do it for them, and, if it’s done for any other reason it’s probably not a very good reason.