When I was a little girl, I often wondered if my father could hear my voice. My grandmother, his mother, told me that he was in heaven. She said he was always watching over me, and I believed her. When my grandmother taught me the Lord’s Prayer, I thought it was about him. “My Father, who art in Heaven.” When I prayed, I thought I was talking to my father.

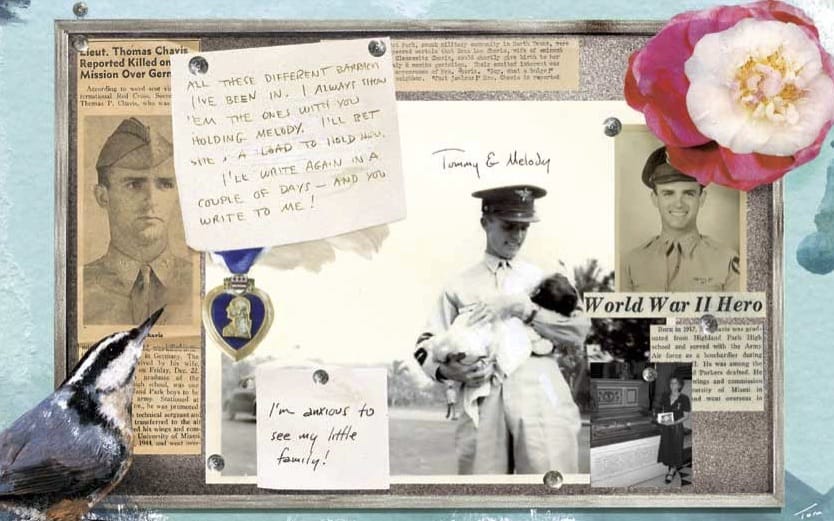

My father was a navigator and bombardier in the U.S. Army Air Corps in the Second World War. He died on October 12, 1944, when his B-24 was shot down on a bombing run over Germany.

I learned this when I was older. When I was a child, all I was told was that my father was “missing in action.” So I always had trouble believing he was dead. In thousands of lonely reveries, I imagined his return. These dreams would always end with him taking me into his arms.

My disbelief has gone through many stages over the course of my life. As I grew older, I realized that he was probably dead, but I still hoped he could be among the missing but alive. As far as I knew, there was no body, no grave, no tombstone, no place to visit. Without some concrete proof of his death, I could let myself think that perhaps he had amnesia, perhaps he was only lost, perhaps one day he would come and find me. Until I was in my twenties, I continued my childhood prayer to him: “Please come back. Please come back.”

I was in my forties when I finally learned what had happened. I visited my father’s sister, who brought out a metal box in which my grandmother had stored old papers. They said my father’s remains had been recovered and were first buried at a prisoner- of-war camp in Germany. Later, I read, the remains were returned to his home state, to Rock Island National Cemetery in Illinois. I was nearly fifty when I found his tombstone there among those of other airmen.

In 1952, when I was nine, Elizabeth, the newly crowned Queen of England, sent a book to all American children who had lost parents fighting for Britain in the war. My book reached me at the desert housing project near the Arizona army base where my soldier stepfather was stationed. I didn’t like the book, with its black-and-white photos of war planes. Many of them had crashed.

In the book was a letter addressed to me and signed by the Queen. She told me that President Eisenhower had dedicated a chapel in St Paul’s Cathedral in London to the sacrifice of Americans who had fought with Britain against the Nazis. In that chapel, my father’s name was inscribed in a special book.

I was sixty-nine when I went to see his name in St Paul’s. This late-life pilgrimage was unfinished business. I was about to retire from my stressful job of more than thirty years helping defend people facing the death penalty. My work was to investigate the lives and family stories of my clients. I’d had little time to look into my own history. Now I would.

Packing for the trip, I decided to take a dress made in the 1940s that I had found years before in a secondhand store. It was made of dark-blue rayon and fell below the knee in the graceful lines dresses had back then. That generation went to war with such flair. Their clothes and hairstyles were so attractive, their dances so sexy, their music so heartfelt and sentimental. So much was lost when those young people, filled with such energy, died. I took the dress along in honor of them.

I had made arrangements with the cathedral ahead of time, because the book of war dead is kept locked away and brought out only for family members. When I arrived at St Paul’s, the enormous dark-red book, bound in faded velvet, had been placed on a table for me to read. Its title was Roll of Honour. A man wearing white gloves opened it, and there, in old-fashioned hand script, on a page of names that all began with “Ch,” I saw my father’s name: Lt. Thomas Patrick Chavis. I wanted to touch it but kept my hand pressed to my waist. I believed, for the first time so deeply, that my father was dead.

My father was one the 28,000 who took off from England in airplanes that never came back. I raised my eyes to read the inscriptions carved in marble around the curved chapel:

They knew not the hour, the day

Nor the manner of their passing.

When far from home

They were called to join that heroic band of airmen

Who had gone before.

May they rest in peace…

The Americans, whose names appear here,

Were part of the price that free men Have been forced to pay to defend

Human liberty and rights.

All who shall hereafter live in freedom

Will be here reminded that to these men and their comrades

We owe a debt to be paid

With grateful remembrance of their sacrifice.

My father’s sacrifice was to lose his life. Mine was to lose a father.

Contemplating these words, I realized that I had not felt gratitude for my father. Instead, I had felt loss, for all that I did not receive from him. I knew that Buddhism has a centuries-old practice of gratitude—grateful remembrance—to ancestors, but I had not applied it in my own life. Now I thought of all that my father had given to me. He was athletic; so am I. He was a writer; so am I. Following in his footsteps, I had dedicated my life’s most productive years to “human liberty and rights.” His gifts to me are many.

I had obtained the official report on the crash of my father’s plane, and with it the names of the ten crewmen who had died with him that day. I knelt there in the chapel at St Paul’s, and suddenly I decided to speak aloud to each of them. Holding the list, I softly spoke the name of each man, his rank and position on the crew, and then the words, “Our boy, our hero, rest in peace.”

I said “boy” because in that war, the soldiers were always called “our boys over there.” Now I am old enough to be the grandmother of these men, and I could talk to them as if they really were my boys.

I said “hero” because I was always told that my father was a hero. I had never accepted that the only father I would ever have was a dead hero. I had wanted simply to have my father. But now, kneeling below the words inscribed for these men, I felt my dead father’s heroism. I felt the continuity of my life. I was at once a little girl and an elder woman. And I was always the same per- son—my father’s daughter.

I have never been in an airplane without thinking of my father. Countless times I have pressed my forehead to an airplane window, watched the surface of the Earth passing below, and thought of his fall through the air. What did he feel? What did he think of?

Now, kneeling in St Paul’s, I opened myself to his consciousness, and I was suddenly certain that my father thought of me, his baby daughter, as he fell to earth. For he had left a lot of evidence behind of his attachment, writing often in letters to his mother of how much he loved me and of his hopes for me.

I spoke to him in the chapel as though he could hear me. What I wanted to tell him was that I, his little daughter, was all right.

Although I often spoke to my father when I was young, this was the first I had spoken to him since I was twenty-seven years old. I was a lonely single mother of two young children then, sharing a cheap, dark, two-bedroom apartment with another young mother and her baby. We were both poor, without protection in the world, and terribly sad. I was folding laundry and imagining my father watching over me. Suddenly I thought, as if awakened from a dream, “No one is here. I am alone.”

With a newfound kind of grown-up toughness, I decided then and there that my father-seeking reveries were unhealthy. I needed to live in the reality of my life, hard though it was. After that, whenever I caught myself pretending he was there, I stopped myself, and gradually, the habit broke.

But that day in St Paul’s, wearing my blue dress with my father’s Purple Heart pinned to it, I felt that whether he could hear me or not, it was good to talk to my father sometimes. That I never needed to stop believing that he in some way protects me. What a wonderful relief it was to re-imagine my father as a benign presence looking over my shoulder. There, I feel, he will remain peacefully for the rest of my life.