You enter a beige brick building like all the others on the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center’s sprawling campus. Here, in an unremarkable maze of offices, something remarkable is happening.

When you reach a third-floor office, there are hints of the mystical experience ahead. In the waiting room, you’re greeted by bright paintings, a crystal tabletop with blue and beige swirls, and a foot-tall amethyst gracing the gray filing cabinet. A set of swinging doors adorns the entry to the hallway, painted with the black silhouette of a face, with multicolored dots trailing off from the head like someone’s mind bursting with delight. It’s the official logo of the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research.

‘One of the reasons that Buddhism came to America and came in the form it did was because of psychedelics.’

Beyond those doors, you find the four psychedelic treatment suites, each with a photo on the door depicting a beautiful wilderness path. Inside, you enter a room that resembles a particularly cozy psychotherapist’s office, with a framed panoramic photo of mountains directly above an oversized white cotton sofa strewn with fuzzy orange throw pillows.

But there are things you don’t usually see in a psychotherapist’s office: a desk with a computer monitor, headphones, and a blood pressure monitor next to the sofa. The monitor is there just in case, to keep you safe throughout your journey, as comforting, in its way, as the soft sofa cushions and pillows. On the end table are a bowl of red grapes and a white rose in a vase. Psychedelic researchers as far back as the 1950s have created similar still lifes for their subjects, as roses tend to “come to life” when the psilocybin sets in.

You take a comfortable seat on the sofa facing the two people who will serve as your guides today. In many of these sessions, one of them is Mary Cosimano, a friendly woman with short brown hair who has a collection of mushroom-patterned socks for such occasions. (The suite is a no-shoe zone, so socks are on full display.) If you’re particularly lucky, the other guide is Roland Griffiths, a gentle, wiry, white-haired man who revolutionized the study of psychedelics in the early 2000s and is now the director of the center.

Your guides are settled on meditation cushions just a few feet from you. One of them offers you a plastic pill case so you can check to make sure it bears your name. Once you verify that it does, a blue pill is placed in a brown clay chalice and presented to you. The other guide offers a crystal glass of water to help you swallow the consciousness-altering capsule.

From there, they help you lie down, cover yourself in a light cotton blanket, put on an eye shade and headphones, and drift off to the center’s playlist full of calming, mostly classical music as you wait for the drug to kick in. Over the next several hours, you’ll experience your mind in ways that go far beyond the ordinary—often profound and insightful, occasionally difficult and frightening, but always with your guides there beside you, sometimes literally holding your hand. Griffiths describes the experience as “a crash course in waking up.”

Welcome to the new frontier in the study of the mind, a place where psychedelics and spirituality—and more than a few Buddhist concepts and practices—are reuniting with science after decades of estrangement.

In the 1950s and sixties, as LSD swept the counterculture, its tendency to produce transcendent visions inspired its share of hippies to turn to Buddhism, playing a key role as Asian spiritual teachings took root in America. Psychedelics “really are what catapulted many of us into studying the dharma,” says Trudy Goodman, the founding teacher of InsightLA.

But as the drug-culture heyday of the sixties and early seventies passed, many spiritual Boomers left psychedelics behind them in favor of meditation. For some Buddhists, any form of drug taking became verboten in light of the precept against intoxication, and it was seen as antithetical to the path to enlightenment.

But today, as psychedelics return to favor in the scientific community, offering great hope for the treatment of addiction, anxiety, and depression, some Buddhist teachers have been reconsidering them as a legitimate way to augment, and even supercharge, one’s practice. And given that some advocates see psychedelic experiences as one of the most direct ways to drive home the interconnectedness of all beings, they could help address everything from racism and nationalism to climate change.

Of course, Indigenous cultures in the Americas have been using psychedelics—“plant medicine”—for millennia. But these substances were largely ignored by mainstream Western culture until the 1950s. As they entered public consciousness, psychedelics and Buddhism intertwined from the beginning.

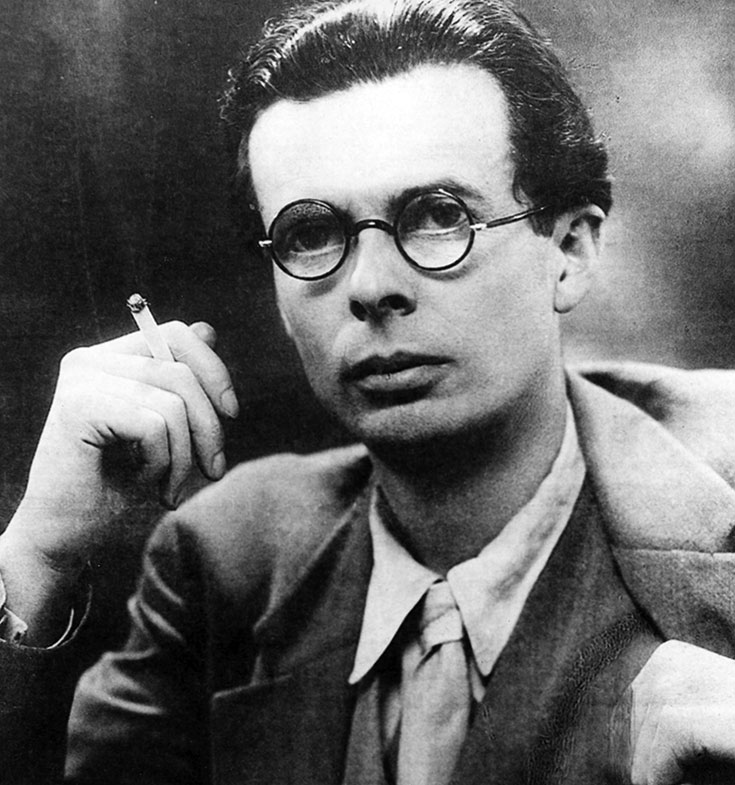

In 1953, writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley was recruited by psychiatrist Dr. Humphry Osmond to participate in his experiments with mescaline in Los Angeles. Huxley had studied Vedanta, practiced meditation, and researched several mystical traditions for his book The Perennial Philosophy. He brought all that to bear on his experience with mescaline, calling to mind a Zen koan quoted by D. T. Suzuki: “What is the Dharma-Body of the Buddha?” Huxley wrote that the answer—“the hedge at the bottom of the garden”—suddenly felt true in a way he hadn’t previously grasped when he had seen it as “only a vaguely pregnant piece of nonsense.” He continued: “Of course, the Dharma-Body of the Buddha was the hedge at the bottom of the garden. At the same time, and no less obviously, it was these flowers, it was anything that I—or rather the blessed Not-I, released for a moment from my throttling embrace—cared to look at.”

Huxley’s work introduced much of the wider world to the psychedelic experience and did so in a way inherently permeated with Buddhism. The Beat Poets, too, helped to popularize both psychedelics and Buddhism in America. And plenty of future American Buddhist teachers had their first major enlightenment experiences via psychedelics, which often led directly to their spiritual seeking and eventual embrace of meditation practice.

Trudy Goodman, for instance, says that during this era she saw something while stoned on LSD that made her almost mad. “It was like, wait a minute, this is my birthright as a human being to know this and see this,” she says. “Why do I have to take a drug to see this?” That question led her to a very practical inquiry: How could she access this wisdom without taking drugs? After all, she was a single mother, and she simply couldn’t be constantly arranging for childcare so she could trip. She needed to be present for her daughter. This led Goodman to Buddhism.

For a time, psychedelics were embraced to a startling degree by the mainstream as a miracle cure for many of the world’s ills. Time and Life magazines began cheering them on as early as 1954, and actor Cary Grant talked about how LSD changed his life in Good Housekeeping magazine, about as mainstream as it gets. The tide began to turn in the 1960s after psychologist Timothy Leary, perhaps LSD’s best-known cheerleader, was fired from Harvard University in 1963 when colleagues raised concerns about his methods, which included a lack of scientific rigor (not using control groups or random sampling), pressuring students to take the drugs, giving them to undergraduates (which was against university policy), and taking the drugs himself while administering studies. Leary’s second-in-command, professor Richard Alpert, was also dismissed. Alpert took off for India, where he studied with Hindu guru Neem Karoli Baba, who gave him the spiritual name Ram Dass. When he returned to America, he became a leader in the New Age movement with his seminal 1971 book Be Here Now.

Leary suffered more of the aftermath, becoming the symbol of the order-threatening counterculture. With catchphrases like “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” he became an easy target for a rising conservative backlash. President Richard Nixon’s administration made an example of Leary in its anti-drug crusade, setting the largest bail ever announced for an American citizen and launching a worldwide manhunt when Leary escaped from a minimum-security California prison, where he was serving time for marijuana possession. By 1966, Life magazine had changed its tune, fretting about “the exploding threat of the mind drug that got out of control” in a cover story about LSD.

Meanwhile, many of those hippies who had life-changing psychedelic experiences began to channel that spiritual awakening into serious study of Buddhism. There, they found concepts like interdependence and no-self that made sense of their psychedelic visions.

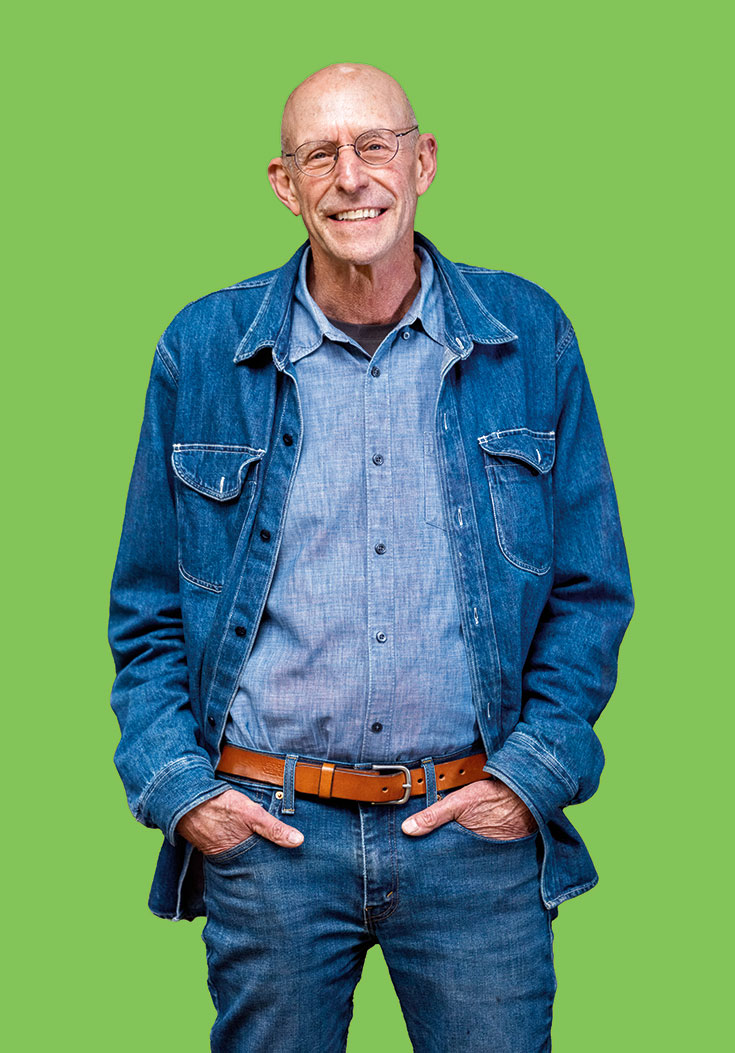

“One of the reasons that Buddhism came to America and came in the form it did was because of psychedelics,” says best-selling author Michael Pollan, who has helped usher psychedelics back into the mainstream with his 2018 book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence and the recent companion series on Netflix. Many of America’s first convert-Buddhist teachers became interested in Buddhism because of psychedelics.

Those teachers, however, found that Buddhism had very clear ideas about how to be a good practitioner, and taking drugs wasn’t one of them. The fifth precept warned students to “refrain from intoxicants,” which caused some teachers to denounce psychedelic use altogether and certainly ended any talk of drug-assisted spiritual practice. Many teachers wouldn’t talk about their early psychedelic enlightenment experiences as part of their Buddhist journey and still don’t.

But it was actually meditation that inspired Roland Griffiths to jump-start the revival of serious psychedelic research. His research then focused on drug abuse, but after he took up meditation he felt called to center his work on something much larger. “Our previous work on addiction was important, but, for me the importance pales in comparison to what all of a sudden came into view: What is the experience of sentience and life awareness, and what are the implications for scientifically understanding those experiences?”

As part of his personal investigation, he began to read about the research on psychedelics, which was done in the fifties and sixties, and realized this was what he wanted to dedicate himself to professionally. He remained skeptical of the grand claims those researchers made about the drugs’ potential. But his early studies clearly showed that psilocybin—a hallucinogenic substance found in some mushrooms—produced “mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance,” one of his published papers says.

Not only did Griffiths’ own life’s work take a turn as a result, he also reinvigorated the field as a whole. Today, rigorous psychedelic research is being done at major institutions such as the University of California, Berkeley, New York University, and at his center at Johns Hopkins.

While taking psilocybin and other psychedelics is not the same as Buddhist practice, the two share significant areas of overlap.

“The key point where they line up is the shift of perspective into nonduality or into the illusory nature of the separate self,” explains Rev. Kokyo Henkel, a longtime Zen teacher who has taught at Santa Cruz Zen Center and Green Gulch Farm and worked with psychedelics throughout his life. “A meditation practice revealing this kind of shift happens in a very controlled environment, a very calm, very stable mind. Whereas when that insight happens in the psychedelic realm, it’s usually not that calm and stable. It’s a little bit chaotic. But within that difference, I think you can find the same direct insight.”

The main effect of psilocybin is that it casts the practitioner into an experience of the present moment. It deactivates the brain’s default mode network, the neurons that produce a person’s sense of self and ruminate on the self when one isn’t engaged with the outside world. “Psilocybin allows one to dispassionately observe and let go of pain, fear, and discomfort, as does meditation,” Griffiths explains. “During psilocybin sessions, we encourage participants to be deeply curious about their experiences and to bring in that intense sense of interest and curiosity and openness to whatever it is that arises in consciousness. This sounds like Mindfulness 101 to me.”

‘A psychedelic lets you take a little helicopter up above the tree line and see the path where you have to go, but you have to come back down. Okay, you saw the way, how do you get there? And that’s what practice is.’

These discoveries have, in turn, inspired a revival of interest in incorporating the drugs into Buddhist practice—and some debate over whether the two are compatible. “To me, it really hinges on the intention with which these substances are being used,” Goodman says. “If the intention is to grow in love and understanding, to have insight into the nature of reality, I do think there can be a lot of benefit from wise use. I say ‘wise use’ because I don’t mean just tripping out. Are you intending to induce heedlessness and intoxication? Do you just want to get high? Or is it more like a boost to cut through being mired in conventional reality? That’s different to me.”

Goodman does not say this lightly. Her brother, she says, was “one of the casualties of LSD.” The drug triggered a manic episode, and he spent years in mental hospitals as a result. Griffiths shares her sense of caution: “The psychedelic renaissance has now taken off, and in some ways, I’m really hesitant about the enthusiasm,” he says. “Psychedelics can be dangerous. People can develop psychotic conditions. They certainly can engage in dangerous behavior to themselves and others. If anything, we’re in a bubble of overenthusiasm.”

But Goodman and Griffiths both believe that the right circumstances make all the difference, as they do for the practice of meditation. Just as meditation is best undertaken with a good teacher, knowledgeable guides are the key to productive psychedelic experiences. They can help practitioners not only feel safe during the experience and avert any disasters, but also integrate the trip’s lessons afterward. “The value of these experiences is the extent to which one can learn from the experience and integrate positive aspects into their day-to-day lives,” Griffiths says. “This is the project of waking up, right?”

Students of Buddhism are particularly able to make good use of the insights psychedelics can offer. When experienced meditators participate in studies, Griffiths finds that they are better prepared for the experience in terms of remaining present and observing their minds. They also often experience shifts in their own practice as a result of the psychedelic experience.

Griffiths has discovered that many find themselves opened up to new approaches—shifting from following the breath, for instance, to an open awareness practice. In a 2018 paper, he and his research team found that “psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors.” In other words, meditators have the best chance of converting the insights gleaned during a trip into lasting changes.

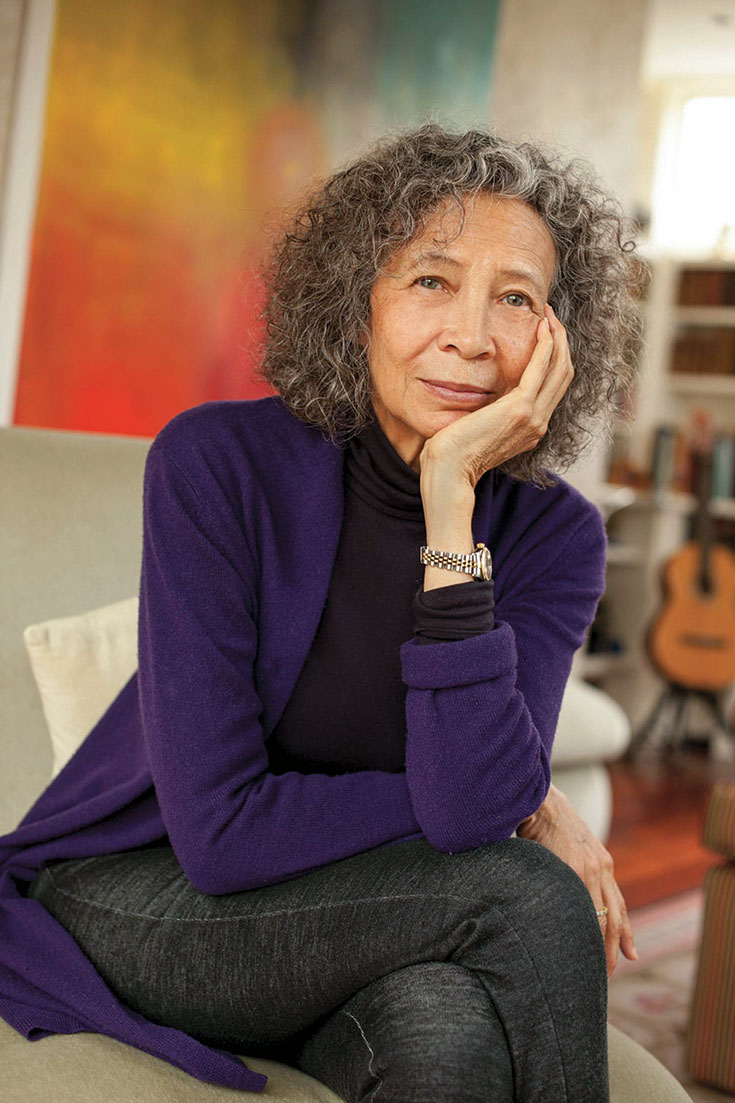

Buddhist teacher Gina Sharpe found herself drawn to psychedelics because she was seeking a profound shift in her practice. Sharpe is a cofounder of New York Insight Meditation Center and was its guiding teacher, but she found her faith in the institutions of Buddhism shaken after running into what she calls a “painful wall of misogyny, abuse of power, and racism” while doing diversity work in the Buddhist community. She recalled her experience with psychedelics in the sixties and thought it might be the only method powerful enough to allow her to process the shock and hurt she was feeling.

So in October 2021, she decided to attend a MycoMeditations retreat in Jamaica, the country where she spent the first eleven years of her life before immigrating to New York. She liked the idea of being someplace familiar, and that the center grew its own psychedelic mushrooms. She would be among a group of about ten participants with three or four facilitators in a beautiful location right on the ocean, with three sessions scheduled over a week.

On the retreat, she had a powerful encounter in the very first session: As she walked down a pathway, she saw another retreatant, who was mid-trip with an eyeshade on and accompanied by a few facilitators. “Who is that?” the woman asked.

One of the guides said, “Oh, don’t worry, it’s Gina.” The woman asked her, “Gina, why are you here?”

Sharpe says, “It hit me, right in my third eye. That is the question that I have been asked by the Buddhist community after my twenty-five or thirty years of service in it. Why am I here?” She began to weep. She understood that what she really needed was not to understand the people who had hurt her, but to see the ways she had idealized the dharma, to renegotiate her own relationship with it.

Though she doesn’t regard psychedelics as part of her Buddhist practice, Sharpe sees no conflict between Buddhist practice and psychedelic use. The drugs, she says, are not intoxicants. Buddhist practice, she says, “is designed to be able to penetrate all of those hidden parts of the mind, right? So why wouldn’t I be willing to take a compound that might facilitate that process?”

Sharpe’s experience was enhanced significantly by the presence of trained guides, just as Goodman and Griffiths both emphasized. The focus on skilled facilitators during this new psychedelic boom seems to be a reaction to the catastrophic implosion of the sixties’ movement with its many psychedelic casualties, and training programs for guides are launching to make sure there are more than enough available as possible legalization approaches. (Oregon has already made psilocybin legal and is working on guidelines for implementing the law beginning next year; Colorado is considering a similar ballot measure this fall.)

Earlier this year, Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, began offering a ten-month, two hundred–hour certification in psychedelic-assisted therapies, combining online instruction and intermittent residential retreats. Given that Naropa was founded by Buddhists and is dedicated to contemplative principles, this underlines the strong connection between Buddhism and psychedelic practice. But Naropa officials are also focused on maintaining the Indigenous traditions that discovered and honored the power of psychedelic medicine and perfected its ceremonial use long before the hippies of the 1960s. The program will also focus on maintaining appropriate boundaries between guides and psychedelic seekers, given the intimacy and vulnerability of the experience.

Naropa President Chuck Lief sees such training as critical to the future of the movement. “I’m not sure I come down on the side of tight accreditation of guides,” he says. “But on the other hand, we know there are a bunch of meditation instructors out there who aren’t very good, and they’re messing around with people’s minds. Here, we’re messing around with people’s minds exponentially more, potentially, because of the medicines.” Given those risks, he says, well-trained guides and facilitators are even more important.

Harrison Rappaport, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, has been working to develop a similar training program at the school’s Center for the Science of Psychedelics. He sees guides as the key to making psychedelics work for large numbers of people. He’s a Vajrayana meditation teacher himself and views the dharma as the best way to use what one has learned from psychedelics.

“Somebody said to me once: Say you’re stuck in a densely forested wood, and you have to get to the other side of it, and you can’t see the way,” he says. “A psychedelic lets you take a little helicopter up above the tree line and see the path where you have to go, but you have to come back down. Okay, you saw the way, how do you get there? And that’s what practice is.”

While Rolland Griffiths sees himself as a scientist first, he also believes that his work is part of a larger arc in human history, something he calls “the Awakening Project” that includes Buddhism and other spiritual and mystical practices. “It really has to do with this fundamental recognition that we’re all in this together,” he says. “What we want people to do is to awaken to that, because we know that when people do awaken to that, they’re going to be more compassionate, more altruistic. The hope is that such changes will neutralize some of our primitive motives that lead to destructive behavior and hurting one another.”

Or, as Michael Pollan says, we’re ready for mainstream acceptance of psychedelics “because we’re desperate. People are like, ‘Bring it on, we need some new tools.’”