I didn’t really know Tyler, but a lot of my friends did. And they were pretty sad when he killed himself last year.

That led people to ask me—not for the first time—what the Buddhist view on suicide is. I gave the same answer I give when I’m asked about the Buddhist view on abortion: I don’t really know. That says a lot about Buddhism. Imagine a person who had studied and practiced Catholicism for nearly thirty years not knowing what the Church’s position on suicide or abortion was. It just wouldn’t happen, because these are very hot issues for Catholics. That I don’t have a ready answer to the question tells you that these are not hot issues for Buddhists in the Zen tradition.

The very prominent suicides by self-immolation that have been carried out by certain Buddhists in Vietnam, Tibet, and elsewhere have led some people to the conclusion that Buddhism sees suicide as a noble act. This isn’t true. Suicide is generally frowned upon by Buddhists as something to be avoided because it tends to lead to a less auspicious rebirth. It’s not believed that one is condemned to Hell forever for killing oneself, the way the Catholic tradition has it, but one is setting up conditions that will make one’s next birth more difficult than the life one chooses to end prematurely. This is because committing suicide causes so much pain and suffering to those who know and love the person who does it.

I take all that stuff about rebirth with a big grain of salt, myself. Even if we really do get reborn after we die, how can anyone say what sort of next life a person is likely to have, knowing only the fact that the person killed himself? There’s a lot more to any individual’s life than just how it ends. For those who believe in rebirth, the entirety of the person’s life determines how he or she will be reborn, not just the last thing the person does.

When dealing with someone’s suicide, vague speculations about rebirth don’t really help. It’s a way to avoid the real question: What do we do when faced with the fact that someone we cared about has killed himself? No one ever knows the right thing to do or say when something like this happens. It’s more important just to be supportive. Discussing what sort of next life the person is likely to have isn’t supportive, I’d say.

If you’d have asked me before that spring day in 1992, I would have told you it was absolutely impossible for me to do any of the things I’ve done since that day.

I came precariously close to killing myself one sunny day in the spring of 1992. My life was shit. I was living in a decrepit punk rock house in Akron, Ohio. My girlfriend had dumped me. I had no money, no skills, no prospects. I’d released five records on an indie label that had gotten some good press but gone nowhere in terms of sales. My dreams of making a living as a songwriter and musician were obviously never going to come true. I felt like all I had to look forward to was eking out a meager existence in the muddy Midwest.

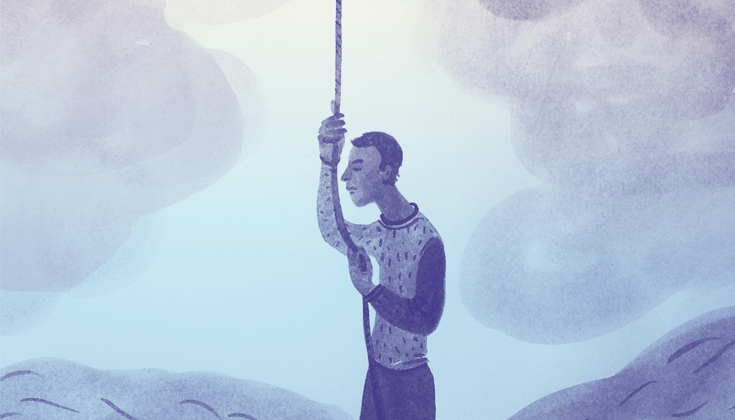

I put a bunch of rope in the trunk of my car and drove out to the Gorge Metro Park, just down the street from where I lived. My plan was to carry that rope out as far away from people as I could, find a sturdy tree, and do the deed.

But when I stepped out of my car I saw some kids playing in the field right near the parking lot. I realized I could never find a spot far enough off the path where there wasn’t some chance a little kid out for a hike, or a young couple looking for a make-out spot, or an old man with a picnic basket and a picture of his late wife, might find me. Then I thought about my mom and how bummed out she’d be if I killed myself. And I thought about Iggy, a friend who’d killed himself about ten years earlier, and how I was still not over that. I put the rope back in the trunk and went home.

That day changed me forever. I decided to live. But I also decided I was no longer bound to anything that came before that day. I decided that conceptually I had killed myself. Now I could do anything—absolutely anything at all.

All the greatest things that have happened to me in my life have happened since that day. Things have been so incredible since then that I sometimes wonder if I’m the main character in some weird existentialist movie and that there’ll be a twist ending in which the audience will realize that I really did kill myself that day.

If you’re contemplating suicide, my advice is, go ahead and kill yourself. But don’t do it with a rope or a gun or a knife or a handful of pills. Don’t do it by destroying your body. Do it by cutting off your former life and going in a completely new direction. I know that’s not easy. I know it might even seem impossible. If you’d have asked me before that spring day in 1992, I would have told you it was absolutely impossible for me to do any of the things I’ve done since that day. It took a lot of very hard effort before things started to change even a little bit. But when they did, they really did.

Maybe that’s not where you’re at, though. Maybe you’re just stuck there trying to figure out how to respond to the news that someone you cared about decided to end her own life. Maybe you just want an explanation. Maybe you just want things to be like they were before. Maybe you wish you’d done something different, said something different, been somewhere where you could have prevented it.

You’re not alone. Everyone who has ever known someone who killed themselves had the same questions and second-guessed themselves the same way. But know that those are just thoughts. They don’t necessarily mean much. The human brain likes to organize things. It tries its best to make sense of whatever it encounters. But some things just don’t make sense. We don’t like that. But it’s the truth.

It’s hard to let go of these kinds of thoughts. But it’s the only way to deal with them. They don’t lead anywhere. They don’t help. Letting go is easier said than done. If you find that you can’t let go even though you want to, then just let go of letting go. Accept the fact that you can’t let go as it is and do something else anyway. Whatever you do is probably fine. See a movie, take a walk, watch the ducks, go to work. Decide to live, and you can do anything—absolutely anything at all.

Please note that clinical depression is a medical condition. The article is not intended to provide treatment options for those who may suffer from clinical depression or other forms of mental illness.

If you are in need of help, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) to access free, 24/7 confidential service for people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress, or those around them. The Lifeline provides support, information, and local resources. You can also text the Crisis Text Line at 741-741 for free 24/7 support with a trained crisis counselor right away.