Below the level of thoughts, concepts and even emotions are the subtle ways that life is felt directly in the body. David Rome explains how this “felt sense” is resolved through the practice of Focusing.

Many contemplative practices with Eastern roots, such as martial arts, yoga, flower arranging and tea ceremony, have become welcome adjuncts to Buddhist practice in the West. Now a practice called Focusing, with roots in Western philosophy and psychology, is being taken up by an increasing number of Buddhist practitioners. They are finding it a valuable means both for deepening their meditative practice and for creating a bridge from meditation to the challenges of living a contemporary Western life.

What is Focusing? It is a practice of bringing gentle, interested attention to one’s bodily felt experience. “Bodily felt” here means the nonverbal texture or affect that lies before or below our conceptual formations. It can be experienced as a vague body sense that is more than just physical—it is the way that our body is holding our particular situation just now.

This body sense or “felt sense,” as it is commonly called, is not the same thing as feeling one’s emotions. The felt sense lies “beneath” emotions like anger, jealousy or desire; it is more subtle and less susceptible to naming. Felt senses are free of the story line that accompanies an emotion: “I am angry because such and such happened.” They are more vague and physical; a person in touch with a felt sense might say something like, “There is this region just under my breastbone that is constricted like a jack-in-the-box.”

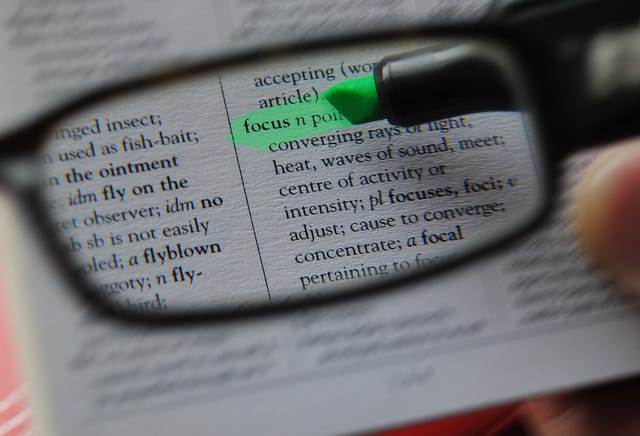

When we first notice a felt sense, it does not have a specific “aboutness” yet. It is nonconceptual. But as we use the Focusing process to be with and listen to the felt sense, it may come into clearer focus (hence the name Focusing) and it may “open” in a way that gives us fresh understanding of our situation. At that point—which cannot be rushed—we can begin to try out concepts on it, begin to inquire what it might be “about.” But the felt sense itself is always primary, not the conceptualization, and the practice of Focusing involves repeatedly letting go of conceptual activity and returning to the body sense.

Focusing has two key aspects in common with Buddhist meditation—suspension of the usual discursive momentum of mind, in order to pay close attention to what is present in one’s experience at the moment, and a spacious awareness that invites deeper meaning to emerge. Focusing is, in Buddhist terms, both a taming-the-mind and an insight practice.

How Focusing Is Done

With practice, Focusing can be done almost anywhere and anytime—in the elevator before an important meeting, during the meeting itself, while walking or driving, etc. But to learn and then deepen a Focusing practice you will want to set aside quiet time, just as with meditation.

Typically, Focusers will find a comfortable sitting posture, then take a minute or two to come into the body. They may do a quick body-scan to help relax themselves and become sensitive to bodily sensations. Then they will “drop down,” gently focusing their attention in the torso region, the whole area from throat to rump. This gets them “out of their heads” and in touch with the parts of the body—heart, lungs, spine, stomach, guts—where we respond at a visceral level. Then they pause there, waiting with a gentle, patient attention that is attuned to felt senses that may be present or may gradually form.

When a felt sense is present, they “keep it company,” as you might do with a young child who is trying to express something that they don’t yet know how to say. After a period of just attending to the bodily quality of the felt sense, the Focuser may try to find a word or short phrase or image that “fits” it. This is called a “handle.” It is not an attempt to explain the felt sense in any way, but is just a textural, visual or metaphorical description of what it feels like just now: “jumpy,” “sticky,” “like a hard ball,” “a squishy place with warm edges.” Usually it has a specific location—in the chest or the belly, on the right or left side—and the Focuser may indicate this with a hand. Sometimes a gesture rather than words will constitute the handle.

The key is that the felt sense itself is always primary. Any verbal handle that comes is checked against the felt sense to see if it fits. The Focuser will move back and forth between the handle and the felt sense, a process called “resonating,” adjusting or replacing the handle until the fit is optimal. You know you’ve got a right fit when the felt sense itself gives a little shift, a kind of easing or opening, a sense of being truly recognized—like being lost in a crowd of strangers and suddenly hearing a friendly voice calling you by name.

This process of resonating encourages the felt sense to emerge more clearly, to come into focus. Then there can be a further step called “asking,” in which we invite the felt sense to tell us more. The hallmark of a felt sense, according to Eugene Gendlin, the originator of Focusing, is that it “talks back.” Some questions it won’t like and won’t respond to, others it will. Focusing questions can be endlessly varied, but classic ones are: “What is the worst of this whole problem?” “What is this situation wanting now?” “What is in the way of everything being fine?”

The magic of Focusing comes when you pose the question and then don’t answer it—not from the head. You wait, just as you would if you were talking to another person and that person was taking their time, groping about inside before responding. You wait, with patient, caring, interested attention, and notice if a response comes in the body. It may not—getting nothing in response is actually a sign that you are really Focusing rather than thinking discursively. Sometimes the felt sense won’t respond to one question, but when it is reframed a little differently, suddenly it does respond. There is a playful, exploring, creative quality to this asking, not knowing in advance what you may get. The not-knowing allows for novelty to arise.

The key to success in this practice is something called “the Focusing attitude.” It is a capacity for gentle and brave self-caring, and it can be cultivated. Also known in Focusing circles as “caring-feeling-presence” or “self-empathy,” it is akin to the Buddhist virtue called maitri—loving kindness or friendliness directed toward oneself. It is a potent, poignant and at times quite magical way of making friends with oneself.

An Example

Right now, as I write this, if I pause and take a few minutes to Focus, I get something like this: …Sensing inside, I notice a tightness in the center of my chest. I give it some friendly acknowledgment, just letting it be there as fully as it can. Then I ask inside: so what is this tightness about? I wait… Oh! Now I see. I am anxious about how this article will be received and I’m feeling a pressure to convince my readers that Focusing is a good thing… Yes, now I see how I’ve been pushing myself to counter all the objections people may have as they read this—that it’s not spiritual, it perpetuates ego attachment, it’s touchy-feely, it’s therapy, it’s self-help, it… Actually, I don’t even need to name the specific objections; I can just have it as this felt sense which I label all that about how people might react. I take a few seconds just to be with that, to let it crystallize—as a felt sense, not as a concept—sensing empathically the pressured place in my body that is holding all that about how people might react.

Now I can ask: what does this need to feel better? Again I wait and listen inside…Yes, now I see. This writing isn’t about proving anything to anyone, and it isn’t about proving myself. It’s about describing this practice which has been so helpful for me, and offering it to others. The readers will know—from their own felt sense—whether it is something for them to explore further. Many won’t. Some will. And that is just as it should be… Now as I check inside again, the tight place in the chest has softened, it has released into some fresh, warm energy to get on with the writing.

Focusing Partnerships

Although it’s a wonderful solo practice that can be done virtually anywhere and anytime, Focusing is most effectively practiced as a regular exchange with another person. My Focusing partner Carolyn and I started our partnership four years ago when we were neighbors. Three years ago Carolyn moved from New York to North Carolina and we continue to Focus together an hour each week—by telephone. In fact, most Focusing partnerships are done over the telephone. It’s a little different from Focusing together in person, but it works surprisingly well—there is a quality of being able to go deeply into oneself while feeling really held by the intimate, caring human presence on the other end of the line.

During Focusing sessions, partners take evenly divided turns as the Focuser and the Listener. During your Focusing turn, you go inside and when you are ready speak aloud what you are noticing. It is like an inner contemplation that is voiced, rather than an ordinary conversation. There is no need to make logical sense or be concerned with whether the other person understands what you mean; unfinished sentences and sudden shifts of direction are common. The Listener, meanwhile, gives friendly, open attention, simply trying to keep company with your process, wherever it leads.

Focusers (like meditators) often attend weekend or weeklong programs with presentations by senior trainers and lots of time spent working in pairs. Some Focusers have more than one regular partner, perhaps addressing different aspects of their lives—personal, work-related, creative, etc.

The Art of Listening

The Focusing training in how to listen is the deepest, most sensitive and most effective that I have encountered. Tracing its lineage to the pioneering American psychologist Carl Rogers, with whom Eugene Gendlin studied at the University of Chicago, and Rogers’ therapeutic use of “Unconditional Positive Regard,” it is nonjudgmental, noninterpretive and highly empathic. More than that, it trains us to really be present for others without losing track of ourselves in the process. While listening we may of course have reactions—feelings, judgments, memories, “helpful” ideas—but our job is always to bring our attention back to the Focuser. We try to notice when the Focuser is in touch with their felt sense—usually the point where the flow of narrative stops and there is silence or incomplete sentences, ums and uhs, an uncertain, groping quality.

Here the Listener has the opportunity to do something radical. Instead of trying to complete the other’s unfinished sentences, offering ideas for solving their problem, or describing a similar experience of their own, the Listener can reflect back key words or phrases that the Focuser has used. The effect is like an echo or a mirror—when the Focuser hears their own words reflected back to them, they have the opportunity to check them against the actual nonverbal felt sense. If there’s a good fit right away, then they experience a sense of recognition and are energized to move on. Often, when they hear the words back, they notice that they don’t quite fit; they don’t do justice to the felt sense. Now, instead of being compelled by habitual patterns of interaction just to keep going, they can use this gap to speak freshly from their experience. Sometimes what comes will be only a very slight adjustment; other times, something quite unexpected and even illogical will come.

Over time the listening skills cultivated in a Focusing partnership will start to appear spontaneously in everyday interactions, leading to a natural kind of deep listening. Stuck patterns of interaction are released and refreshing new energy and insight emerge in one’s conversations.

Focusing and Meditation

Focusing can be a wonderful companion practice to Buddhist meditation. Robert Aitken Roshi, the dean of American Zen masters, recommends Focusing to his students as a way of preparing for meditation. In a recent communication to Eugene Gendlin, Aitken Roshi says, “I’m glad that you find many Buddhists interested in Focusing. I continue to recommend the practice from time to time in personal interviews, and students report worthwhile results. I treat it as a preliminary practice for the noetic work involved in zazen, where a quiet mind is important.”

Focusing often begins with a step called “Clearing a Space,” which can be used equally well as a precursor to meditation. It consists of taking time to notice anything that is being held in a bodily way—a worry or a need or some unresolved situation. By giving each such issue a moment of acknowledgment—without “going into it”—the issue can relax a bit, enough so as not to be in the way of what you choose to stay with, which might be a particular situation or challenge if you are Focusing or, in meditation, the technique itself. Clearing a Space is like noticing a needy child—just a brief moment of complete, caring attention is often enough for it to take comfort and relax its claim on your attention. Issues are not suppressed—they may reappear in one’s Focusing session or one’s meditation session—but their urgency has been relieved enough that we can settle down.

A second way in which Focusing complements meditation is by offering a contemplative bridge between formal practice and living in the world. Most of us are not renunciates; we have not abandoned home and family and friends and worldly involvements. And while meditation trains us to have more space around the demands of our lives, it doesn’t always give us direct insight into how to work with them. Of course such insight may arise spontaneously, but meditation in and of itself does not aim to solve problems—its primary goal is to solve the haver of the problems.

Focusing shows us how, in a separate gesture from meditation, to deliberately invite a situation, problem, decision or creative challenge into the center of contemplative awareness and give it patient, caring, interested attention. Then the situation may begin to unfold, opening up in ways that bring fresh understanding and a shift in how we hold it. Often this will lead to pragmatic insights—“action steps”—which we can use to resolve aspects of our life that feel stuck, bringing welcome forward movement.

Focusing is very much about how we engage our lives, our relationships, surroundings, work challenges, hopes and fears, etc. It is also a powerful antidote against “spiritual bypassing,” which John Welwood, in his excellent book Toward a Psychology of Awakening, describes as “using spiritual ideas and practices to sidestep personal, emotional ‘unfinished business,’ to shore up a shaky sense of self, or to belittle basic needs, feelings and developmental tasks, all in the name of enlightenment.”

Thirdly, and perhaps of greatest interest, Focusing can have a crucial impact on the quality of our meditative experience itself. Although different schools of Buddhism present a wide variety of techniques and approaches to meditation, most of them are rooted in the Buddha’s original teaching on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness in the Anapanasmrti Sutra, which prescribes “bare attention,” or simple noticing of what arises in one’s consciousness from moment to moment. But in practice a problem can arise here.

Much of what occurs in our awareness is like the tip of an iceberg, showing only a fraction of the whole. If our practice of bare attention is too strict, or too casual, we may end up jumping from iceberg tip to iceberg tip, so to speak, without ever recognizing that there is a much larger “something” underlying the thought or emotion or physiological tweak that we consciously notice.

In the initial stages of taming the mind, this sort of mere noticing is desirable, since we are learning not to “go into” sensations or perceptions discursively. But there is also a quality of ignorance—like momentarily glancing at all the people we run into, but never feeling the full presence of any of them. Here Focusing shows us a middle path, a way of sensing the “whole” of what is arising without going along with the propensity to get discursive. It is like taking a full moment to really take in the person whom you are encountering—this person, right here, just now—yet not entering into conversation with them.

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche talked about mindfulness meditation as a process of “touch and go.” “Touch” means really acknowledging, really appreciating, the texture of a particular mental content, not just bouncing off of it. It is the difference between a gentle squeeze and a superficial tap. This touching, acknowledging, appreciating, is the seed for developing insight—a way of being present to phenomena that invites fresh meanings to emerge. Because Westerners tend to be more split off from the experiential body than people in more traditional cultures, the practice of Focusing can facilitate our ability to touch genuinely what arises in the mind-heart in a nondiscursive way. As Pema Chödrön recently advised a questioner with doubts about her meditation practice, “There is a secret ingredient—direct, nonverbal experience.”

Focusing and Western Philosophy

A few words concerning the basic view from which Focusing proceeds may be useful. Philosophically, it traces its lineage to Phenomenology, a movement in twentieth-century Western philosophy that emphasizes the primacy of direct, first-person experience over abstract metaphysical claims. For instance, rather than Descartes’s assertion, “I think, therefore I am,” Phenomenology wants to know, “What is the actual experience of thinking, divested of any ideas we have about it? What do we notice if we simply attend to the phenomenon itself?” The parallel with Buddhist meditation is apparent.

The practice of Focusing was developed in the 1960’s and 1970’s by Eugene Gendlin, Ph.D., a University of Chicago professor, now emeritus, who is a practicing philosopher and psychologist. Gendlin has carried the Western intellectual tradition forward—beyond both Modernism and Post-Modernism—in his radically nondualistic, process-oriented “Philosophy of the Implicit.”

Gendlin begins from a premise he calls “interaction first,” meaning roughly that life process precedes all entities or objects. An animal, including a human animal, is an ongoing interaction with its environment. We do not appear from nowhere and only then start to interact with the environment; rather we always were, and still are, a process that forms together with its environment. This is true from an evolutionary perspective as well as for any individual life. Gendlin says that a person is not a thing or even an organism but a carrying forward.

This carrying forward, or “life forwarding,” expresses itself in functional cycles such as eating-digesting-defecating-eating again. But a cycle can become blocked. We may be ready to eat but no food is available. Then the “blocked process” gives rise to a bodily sensation that we label hunger and implies an object that we call “food.” But hunger and food, like all concepts, are abstractions from immediate experience. They cannot do justice to the fine texture of the actual lived instances they try to describe. Beneath the generalization called “hunger” lies an intricate bodily knowing of just this exact situation that I am now in, and only from this specific, living intricacy can I know what moves to make to satisfy my hunger in my present circumstances. Do I go to the kitchen cupboard? To a restaurant? Try some new food I’ve never had before? Or perhaps it’s not food at all; maybe my hunger is better met by getting in touch with a friend or going for a long walk in the woods.

As human beings, our total life experience up to this moment always implies further growth, a further unfolding. Until it actually occurs, the form of this further growth can’t be known; it is only implicit (hence Philosophy of the Implicit). When it comes, it will be an infinitely precise response to actual circumstances and it will be novel, because nothing exactly like this will have ever occurred before. So, for example, when I meet a person for the first time, my experience will be akin to many encounters I have had before, yet it will be completely fresh: I have never experienced another person just this way before.

Focusing makes no pretense of being a “complete path.” On the contrary, it offers itself as one tool among many for growth and transformation. Although it can certainly be a person’s primary contemplative practice, Focusing loves to join with other practices and methodologies and to enter into fields as disparate as education, healthcare, business, the arts, psychology—and of course spirituality. It seems to me that for all the discourse these days about uniting spirituality and action in the world—often at conferences specially convened around this topic—we are still in the very early stages of knowing how we might actually accomplish such a union in the context of contemporary life. The practice of Focusing can illuminate and energize our efforts to mix meditative discipline with skillful action in the world.