Steve Aoki stands at the stage’s edge, balancing a sheet cake in one hand. The atmosphere is electric. With the aim of a seasoned archer and the glee of a kid chucking a water balloon, the world-renowned DJ launches the confection into a sea of fans (one holds a “CAKE ME” sign). Time seems to slow as it arcs through the air, frosting glinting under the strobes. And then—impact. An explosion of sugar and cheers as someone takes the hit, arms raised in triumph, their face smeared in sweet victory. Welcome to the party.

The spectacle, the connectivity, the sheer joy and absurdity of it all—this is what Aoki lives for. Performing over two hundred sets annually, he spends even more days on the road; in 2012, he claimed the Guinness World Record as most well-traveled musician in a single year. (His shows also once broke records for the longest crowd cheer and the most glow sticks lit for thirty seconds.) In addition to “caking,” which requires approximately ten locally sourced cakes per show, each made according to a detailed rider, he’s been known to spray his audience with champagne, stage dive, and crowd-surf—sometimes atop an inflatable raft.

“We all sometimes float away, but when we want to stay grounded and be the best person we can be, it’s always about being deliberate.”

But behind the wild antics and larger-than-life performances, there’s a bedrock of discipline and intention. While Aoki has a keen interest in biohacking and self-optimization, it’s his commitment to mindfulness and gratitude that grounds him—a staunch belief in their power to transform a life. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, he hosted a virtual “Mindfulness Marathon” through the Aoki Foundation, his charity dedicated to supporting brain science and health. By spotlighting experts like Headspace’s Andy Puddicombe, Aoki sought to offer calm, clarity, and connection at a time of widespread uncertainty.

“The mindfulness practices, the thoughtfulness practices of Buddhism, are something I try to practice consistently,” says Aoki. “We all sometimes float away, but when we want to stay grounded and be the best person we can be, it’s always about being deliberate—about not living in a passive state of consciousness.”

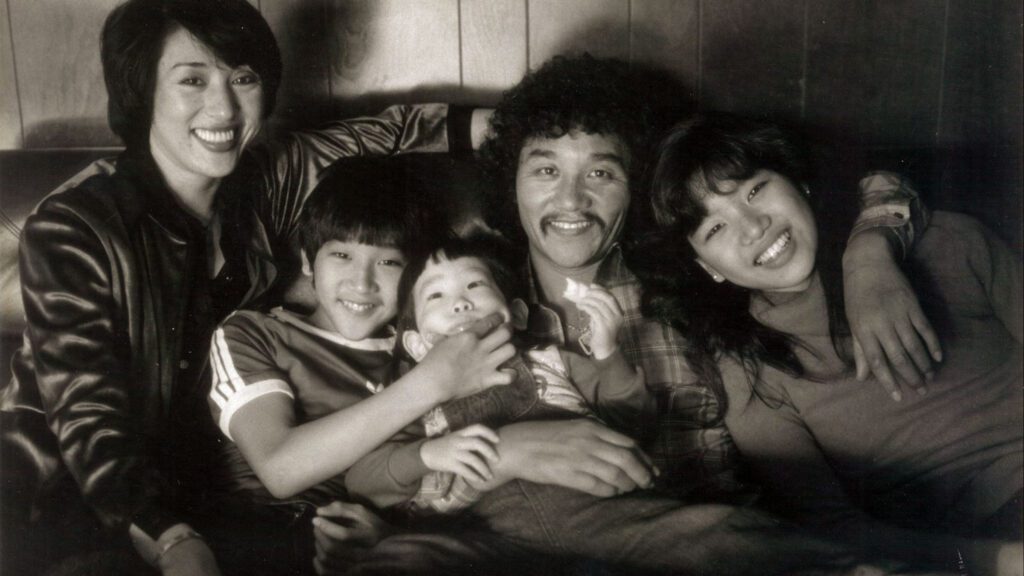

Steve Aoki, the child of Japanese immigrants, doesn’t consider himself a religious person. “But,” he says, “because I grew up with a very devout Christian mother that I absolutely adore and would do anything for, that is my default.” Though his spiritual practices may differ from hers, the values she instilled in him—kindness, respect, and service—remain at the core of his beliefs.

A devoted mother, Chizuru Aoki raised Steve and his siblings in Newport Beach, California, with compassion and selflessness. After discovering that her husband had fathered a child with another woman (whom he eventually married), she divorced him in 1981, when Steve was four years old.

While his mother provided a steady foundation, his father, Rocky Aoki, was a whirlwind. Their contrasts were striking—where Chizuru Aoki found fulfillment in home and family, Rocky Aoki was frequently away, thriving in motion, constantly chasing the next challenge. And so, he was many things: the founder of the iconic restaurant chain Benihana, an Olympic wrestler, a professional powerboat and car racer, a world-title-holding backgammon player, and even a record-breaking adventurer. (In 1981, he set a thirty-four-year record for the longest hot air balloon flight, traveling across the Pacific Ocean before crash-landing in Northern California.) He also happened to be a Buddhist, though Aoki doesn’t know the specifics of his father’s tradition or practice. “He did wear this Buddhist necklace here and there, so he wanted to show it,” Aoki recalls.

His entrepreneurial father became a poster child for extravagance, embodying an embrace of American culture. A flashy dresser, he permed his hair into a trademark Jheri curl so that white Americans would distinguish him from other Asians. Yet, his Buddhist connection seemed quietly present, largely hidden from the public eye. “I would say his religious side, his Buddhist side, was more in line with Japanese cultural humility,” says Aoki of his father. “So, he wasn’t putting it out there. It was very personal.”

The term “nepo baby” gets thrown around a lot lately, but despite his father’s success, Aoki wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth—or a teppan-yaki turner in his hand. Benihana was far from a birthright for Aoki; he spent summers peeling onions and working on the kitchen assembly line, while his father was adamant about never handing him anything. All Aoki really inherited was his father’s genes, name, and work ethic.

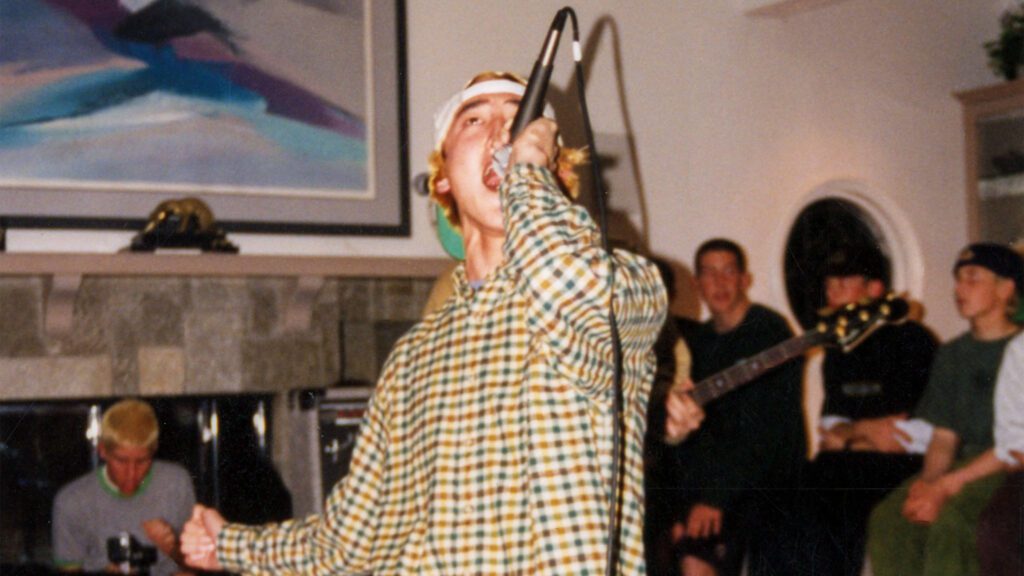

While attending UC Santa Barbara as a women’s studies major, Aoki was involved with student activism and immersed himself in the DIY (do-it-yourself) music community, both playing in bands and hosting them. He turned his living room into a makeshift venue called “The Pickle Patch,” which became revered as the heart of the local punk scene.

This raw, high-energy world eventually led the then nineteen-year-old to launch Dim Mak Records in 1996. Named after a fabled martial arts move—in homage to Aoki’s childhood hero, Bruce Lee—the indie label would go on to champion hitmakers like Bloc Party, The Kills, and The Chainsmokers. But in Dim Mak’s infancy, Aoki spent years scraping by, juggling minimum-wage jobs at a call center and delivering food on his bike, pouring more money into the label than he was making.

Finally, in 2003, came the weekly Hollywood party that turned the label into a full-blown movement: Dim Mak Tuesdays. With then rising acts like Lady Gaga, M.I.A., and Justice onstage, the legendary party became the beating heart of indie sleaze. Aoki never set out to be a DJ—he just filled the gaps between sets, and faced a steep learning curve—but fate had other plans for the intrepid producer. Since his meteoric rise, he’s become the author of a memoir and a graphic novel/manga and an enthusiastic biohacker. Plus, he’s expanded Dim Mak to include a fashion brand.

In many ways, Aoki embodies both his parents’ influences: his father’s relentless drive and his mother’s quiet resilience. Despite a life of constant motion, he carries a sense of groundedness and gratitude. “My public persona is loud. And it’s very messy—I got cake everywhere,” laughs Aoki. “And then I come home: it’s pretty quiet. I don’t have music playing unless I have my studio on or if I’m working out. I meditate on a regular basis. I do a lot of mindful practices when I’m at home. And my personal life—I don’t like displaying it all the time on social media. That side is not really the side that I really care to show everyone. The cakes, that can go out; that could be the viral moment. But my personal life—my family, my wife—I try to safeguard those things.”

In a world of endless distractions—social media, autoplay, constant scrolling—it’s too easy to become, as Steve Aoki puts it, “the passenger in the car.” And that’s why mindfulness is so key for him.

It would be easy to assume that Aoki’s approach to mindfulness stems from his cultural heritage—either his Japanese roots or his Californian upbringing. But in actuality, Aoki attributes his initial understanding of mindful living to the music influences of his youth: punk rock and hardcore. “Most people wouldn’t see that as a way to onboard into this kind of thinking, but through that world, when I was a kid, I learned about vegetarianism,” remembers Aoki. “I started questioning, ‘Hey, do we really need to eat these animals that have emotions and real lives in order to sustain ourselves?’”

The punk and hardcore music scenes that he speaks of, particularly in the eighties and nineties, weren’t just about loud music—they were an entire ethos. Fueled by a DIY mentality and a proverbial middle finger to the mainstream, this rebellious spirit spilled into ethical living too. Straightedge punks swore off booze and drugs in favor of self-discipline, while veganism fit right in with the community’s stance against capitalism, exploitation, and oppression. Both were more than just lifestyle choices—they were battle cries for integrity, social justice, and a more compassionate world.

“The calmest place in all the chaos is right in the middle. If you’re on the outside, you’re going to be spinning like the tornado. But if you’re right in the middle, it’s all around you.”

“I was thinking about that when I was fourteen, and it never would have entered my mind unless it had been brought to me through the hardcore scene,” says Aoki. Growing up Asian in mostly white Newport Beach, he often faced racism, yet he found refuge in the outsider-friendly hardcore community. “That opened the doorway to thinking differently, instead of just going through life the easiest way possible,” he says.

After college, Aoki eventually broke edge and began drinking recreationally. As his career took off and the party culture around him escalated, his consumption increased. But when his close friend DJ AM died in 2009 from an overdose, Aoki was forced to reevaluate his relationship with alcohol. Determined to cut down his intake drastically, he adopted a more mindful approach to his lifestyle and art, arguably reflecting the spirit of his original music roots.

Aoki sees other links between punk ideology and mindfulness. “With hardcore and punk, it’s a lot of chaos. So, it’s about throwing yourself into the tornado and being the model fit for that kind of thing,” he says. “Then you realize the calmest place in all the chaos is right in the middle. If you’re on the outside, you’re going to be spinning like the tornado. But if you’re right in the middle, it’s all around you. And if you can control that, that’s a superpower. If you can get to that place mentally, in all that life throws at you, you can handle a lot.”

When a health scare arose in May 2015, the in-demand DJ was forced to cancel multiple European tour dates to undergo emergency surgery to remove a large nodule on his vocal cords. As part of his recovery, he would need to remain silent for a month as his throat healed.

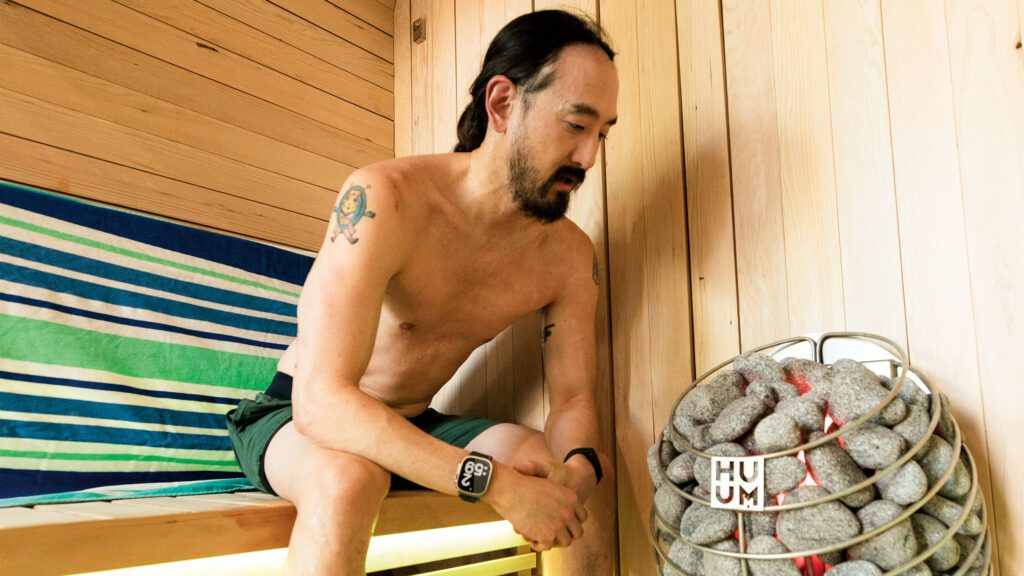

Aoki had dabbled in meditation before, but doubted he was “doing it right.” He’d have distracting impulses—feeling bored, wanting to check his phone—and constant questions running through his mind: “Is this working or is it wasting time?” But when he knew his intense schedule had suddenly been cleared, he saw it as an opportunity. He hired a meditation teacher, a woman who specialized in transcendental meditation, and for a couple of hours a day, they’d sit in silence.

“I remember the first day,” Aoki recalls. “It was awkward, because she’s sitting there, and I’m just not sure if this is really coaching.” It wasn’t the kind of training he was used to, but he stuck with it, going through the motions—or, rather, lack thereof—unsure if anything was happening.

Then, on the fifth day, something shifted. The word she had given him as a mantra started to take hold. His mind entered a trance-like state, and for the first time, he understood what meditation could do: “TM got me to not stress on anything coming to the mind. It got me to the place of just focusing on the word. And then I started interpreting what that focus could be. It doesn’t have to be a word. It could be me in a visual setting, staying in that setting.” Meditation, he realized, wasn’t about shutting thoughts out but about sitting with them, letting them come and go.

But getting there wasn’t easy. “Anytime you try something new, especially when you’re older…your brain is stubborn,” Aoki admits. “It says, ‘Don’t do it, you don’t need to do this.’” The mind resists discomfort, craving familiarity, but he learned to push through. “You have to fight your ego and be like, ‘Shut the fuck up.’”

Eventually, meditation became a ritual, a necessity. He meditated morning and night, no matter where he was: “I would be on tour, sitting on the cliffs of Ibiza right when I woke up, meditating. At sunset, I would go and sit and meditate. On a plane, I would find every place to do it.” Over time, Aoki developed his own way of engaging with transcendental meditation, layering visual elements with the mantra.

The practice deepened Aoki’s connection to his own body, and he developed a love for body scan meditations. “Once you get better at that,” he asserts, “you can really start sensing if there are issues in different parts of your body by honing in on how connected the mind is to the rest of the body.” Meditation, once a seemingly elusive concept, had become his anchor—a way to remain centered, no matter how frenzied the world around him became. “That was one of my visuals: me sitting in a tornado, everything chaotic around me, and I’m completely impenetrable,” he says.

One might think that maintaining focus would be a challenge during the sheer madness of his shows, but for Aoki, it’s the opposite. “The best shows are the ones that you’re absolutely present in, and you’re forced to be present,” he explains. “Everyone’s staring at you when you’re up there on stage. I mean, if you’re aloof, daydreaming, there’s something wrong. You have to be completely on. It doesn’t matter how you felt before—if you got into a fight or argument, or if something bad happened. It doesn’t matter once you show up on that stage. Everyone’s in this state of excitement, in this beautiful, vulnerable state of emotion. It’s freeing.”

Beyond the adrenaline, there’s a deeper connection happening. “Sometimes I see people absolutely bawling, singing their hearts out, or just crying, because they’re in this experience. Your heart melts. You’re connected to that person, you know? It’s like a platonic love affair; we’re connecting through music,” says Aoki. “There’s nothing more beautiful than that, especially between strangers. I feel so close to them, the ones who are connected to that experience, that song, that moment.”

For Aoki, these raw moments are where everything aligns. “The deeper these emotional moments are, the more present you are, the more connected you are,” he says. “And that’s why music is such a strange thing. It’s so powerful.” That power is in the way it breaks down barriers, making people feel seen, understood, and part of something larger than themselves, he concludes.

Aoki’s journey has been anything but linear, shaped by twists, turns, and constant reinvention. The tornado grows, his universe expands—music, fashion, biohacking, research, philanthropy. But through it all, he’s learned that pushing forward isn’t just about acceleration; it’s about balance. “You can’t just put yourself in the red all the time,” he says. “Your body needs to find that center, that grounding, that mindfulness to give to yourself.” Even at his most explosive—tossing a cake, igniting a crowd—it’s not about excess, but connection. In his hands, the cake is more than a gimmick; it’s a focused offering, a moment of shared delight. Aoki remixes a parable of privileged detachment into one of community: Let them eat cake, together. It’s a reminder to be here, now, and to embrace the delicious, sometimes messy joy of the moment.