Spirituality and art, even in the supposedly soulless and money-driven place that is Hollywood, are closely connected. How can a creative person not seek to understand the deeper meaning behind our existence?

When I interviewed George Lucas, he said it was being flung through a car window in a high-speed crash when he was a teenager—in the days before airbags it was only his seat belt snapping that saved his life—that made him take his wayward life in hand and seek to excel at filmmaking. The spiritual awakening it provoked also found expression in The Force, that mystical notion of balance which pervades his Star Wars universe. David Lynch, whose films seem like evanescent dreams captured and writ large upon the big screen, told me he avoided psychotherapy because he feared it would affect his creativity—but he is a tireless advocate of Transcendental Meditation.

But Benedict Cumberbatch’s story is in a way the most striking of all. In a few short years since taking on the role of a modern-day Sherlock Holmes in the phenomenally successful BBC series, the thinking person’s heartthrob has become recognized as one of Britain’s greatest actors. He has appeared in blockbusters such as Star Trek: Edge of Darkness and The Hobbit and prestige films like 12 Years a Slave and The Imitation Game. Recently he lit up the London stage in that most demanding of all roles: Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Some critics ascribe his success to the training he received at LAMDA, one of Britain’s top drama colleges. Or to the ten years before Sherlock that he spent, relatively unsung, combining theatre with TV and film roles such as Stephen Hawking (ten years before his friend Eddie Redmayne scooped the Oscar for the same role) and a sleazy millionaire rapist in Atonement. But when I met the actor, he put his success to down his time teaching English in his pre-university gap year to Tibetan Buddhist monks at a Buddhist monastery near Darjeeling, India.

“I’d always been fascinated by the idea of meditation and what it meant,” Cumberbatch told me. “In India, I went on a retreat with a lama—several days of incantation to clear and purify the mind—along with a dozen other people. It was incredible, and I kind of floated out of there after two weeks. When you’ve been that still and contemplative, your sensory awareness is heightened and more sharply focused. You’re taking in detail to the point where you have to pause a little bit. It was amazing.

“Stillness is an essential part of acting,” he continued, “so I already had a certain amount of focus in that beforehand. A still point is a very, very hard place to find, especially among the usual kind of pulped sheep pushed around by the blinking flashing world of modern technology.”

His Buddhist training, he reflects, was particularly important in coming to grips with the career-defining role of Sherlock.

“Sherlock Holmes is an interesting character,” he explains. “He’s someone who has to push a lot aside. He has ways of shutting out white noise, like scraping away badly at a violin. One of these is he’s rude to people, telling them to shut up all the time.

“I think there’s a real parallel—as an actor, you have to be able to shut out distractions. I’ve had some pretty knockout moments, like the press night of a play called The City by Martin Crimp. A phone rang in the audience for about five minutes. That took a lot of concentration!”

Cumberbatch is a joy to talk to: animated, articulate, adopting a range of voices when telling an anecdote.

“This is a conversation fueled by coffee,” he half apologizes at one point, when he’s been talking nonstop for ten minutes. “I’m trying to pack a lot in—I don’t speak like this all the time, because I have a relationship with other people that wouldn’t last!”

But there’s a deeper reason why, although he takes his craft seriously, he doesn’t take himself too seriously; why he remains famously one of the nicest and most unaffected of major stars. It was the Tibetan monks who taught him that you don’t have to be boring to be serious about your profession or your spirituality: that humor is an intrinsic and necessary part of life.

“They were amazingly warm, intelligent, humorous people,” Cumberbatch recalls with a smile. “Hard to teach English to. I built a blackboard, which no previous teachers seem to have done. With twelve monks in a room, with an age range of about eight to forty, that’s quite important. The reward–punishment thing of sweets or no sweets, or game or no game, worked quite well. But they taught me a lot more than I could possibly ever teach them.”

And what was that, exactly, I ask? “They taught me about the simplicity of human nature, but also the humanity of it, and the ridiculous sense of humor you need to live a full spiritual life.”

A specific example is not long in coming. “There was a time when these two dogs were all over each other, screwing in the backyard, and all of this laughter. ‘Sir, sir, quick, come, sir, sir, quick!’ These two dogs were stuck together like a pushmi-pullyu [the two-headed animal in Dr. Doolittle]. The monks were on the floor laughing. It was so funny. They were like, ‘Kodak moment, sir, Kodak moment!’ Brilliant!”

He chuckles to himself, reliving the moment, and his enthusiasm is infectious. In fact, there’s only one point in our conversation when the laughter stops. That’s when he is reliving a harrowing experience when he confronted the imminence of his own violent death. It’s an experience that left him more spiritually minded—and eager to seize life with both hands.

Benedict Cumberbatch was filming a BBC mini-series called To the Ends of the Earth in South Africa in 2005 when he and his friends were carjacked by six armed gunmen. His hands were bound, and he was forced into the car’s trunk and driven on bumpy tracks off the main road.

When the car stopped, he was dragged out and ordered to kneel in the dirt alongside his friends, with a duvet covering his head. He was absolutely certain that they were all about to be shot dead. All he could think of was to talk—telling the gunmen it would be foolish to shoot them, that it would just cause them difficulties to have a dead English actor to dispose of. It must have been the performance of his life (literally), because the kidnappers left them there and took off.

After that, he tells me, “I went a bit nuts. I went to the ends of the earth in Namibia and went on an adrenaline-junkie thing in Swapismund. Because when you’ve been forced to look into the idea that you die on your own, you kind of go, ‘Oh, okay, well if I’ve got my own company at the beginning and the end of this life, I might as well do a few crazy things with it under my own steam.’

“It was, I suppose, the polar-opposite reaction to becoming agoraphobic and internalized and haunted—there’s enough of that in my work! I didn’t want that small incident to put me off the beauty of Africa. I wanted to be part of the people again and not fear them.”

It’s a wonderfully enlightened response to an incident that might have emotionally crippled another person. That it only deepened his keen sense of social injustice and deep love for his fellow man was made abundantly clear during his run in Hamlet. When Caitlin Moran, a journalist and author who had previously interviewed Cumberbatch, asked him to contribute to a charity single in aid of Syrian refugees, he readily agreed. From his dressing room, he recorded a video of himself reading from the poem Home: “You have to understand that no one puts children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”

His involvement did not end there. Every night at the Barbican Theatre, after the curtain call, he broke with tradition by getting out a collection bucket and uttering a personal plea to theatergoers from the stage. Toward the end of the run, in late October, he made headlines around the world by uttering an impassioned “Fuck the politicians” during his speech. It was not the sort of language British theatre-goers are accustomed to when they sign up for a night of Shakespeare. The actress Samantha Morton, for one, supported his criticism of the response to the refugee crisis, saying she “cannot fathom how certain individuals within our government can sleep at night.”

Cumberbatch raised more than a quarter of a million dollars in donations from audiences. Would he have acted in this way without his time spent with the Tibetan monks? Without having had his own brush with death?

Cumberbatch is reluctant to talk in too great detail about his personal and spiritual beliefs, but he gladly describes himself as a Buddhist—“at least philosophically”—and says he is drawn to the “transcendent.”

It’s easy to see why, once his fame in TV and film had earned him his pick of theater parts, he elected to play Hamlet. It’s not so much that it is the Everest that every actor simultaneously dreads and longs to climb. In fact, Cumberbatch is characteristically modest about that aspect, saying self-deprecatingly when he first announced the project, “I mean it’s a very vain project in a way, isn’t it, Hamlet, because every actor wants to have their go at it, but, um, I do want to have my go at it.”

It’s more because Hamlet is such a spiritually questing play: from the appearance of the ghost of his father, to his agonizing over whether “to be or not to be,” and especially the key line, “And thus the native hue of resolution is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought.”

Hamlet knows he should act to avenge his father; but in thinking overmuch on the rights and wrongs, and the when and how, he fails over and over to do it. That is the crux of and tension in the play. Cumberbatch played the part with an unusual amount of physical humor—acting like a toy soldier in the mad scenes—which made this a more action-oriented and less thought-crippled Hamlet than any of the dozen-odd productions I have previously seen.

Having spent more than an hour in Cumberbatch’s company, and marveled at the speed and articulacy at which the thoughts tumble out of him, it’s clear there is a reason he is so frequently cast as super-smart men—Stephen Hawking, Alan Turing, Sherlock Holmes. Intelligence is a quality that is very hard to fake, if an actor does not possess it already.

But watching his performance as Hamlet, you realize that Cumberbatch, in common with Shakespeare’s sweet prince—and with Sherlock—must feel that the speed of his whirling brain is as much a curse as a blessing.

“I love the outdoors, throwing myself out of planes, that sort of thing,” he says at one point during our interview. That’s one way to, as it were, get out of your mind. Buddhism, and the quieting of thoughts, and the stillness that comes through meditation, is perhaps the more constructive route.

“Sometimes as an actor you’re looking for the infinite,” he says. “If you can hold that, if you can remember that in the chaos, it will anchor you and give you grace and ease.”

Cumberbatch was an unknown young English teacher when he made his connection to Buddhism at a Tibetan monastery in Darjeeling. He returned to the Himalayas as one of the world’s biggest movie stars.

It was his role as Doctor Strange in the upcoming film that brought him to Nepal, which was standing in for the mythical Tibet where the comic-book hero learned his “mystical arts.” Cumberbatch told the Wall Street Journal that he was very excited about the “spiritual dimension” of the film, which he said was “a huge dimension of my life, obviously. I meditate a lot.”

He filmed scenes in some of the famed sites of the Kathmandu Valley, such as the Swayambhunath stupa and the sacred Hindu temples and cremation grounds of Pashupatinath. It was only natural to take some time off from filming and reconnect with the monastic tradition that had inspired his interest in Buddhism.

In the Tibetan enclave of Boudhanath, the cobblestone streets around the famed stupa are home to some of the most important monasteries of the Tibetan diaspora. The largest, Shechen Monastery, was founded by the late Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the most influential Tibetan teachers of the twentieth century.

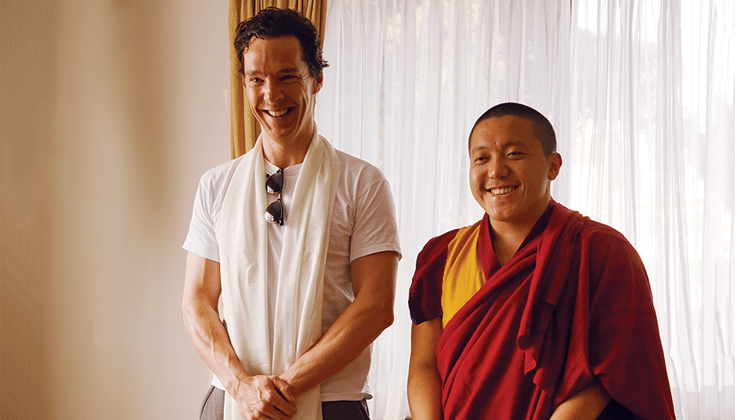

There, Cumberbatch, joined by costar Chiwetel Ejiofor and close friend Adam Ackland, had a private audience with the young Buddhist teacher recognized as Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s reincarnation. They had what was described as a lengthy and fascinating conversation about Buddhist philosophy and practice. Afterward, a beaming Cumberbatch was photographed with Dilgo Khyentse Yangsi Rinpoche, wearing the traditional white scarf called a kata that signifies an honored guest in Tibetan society. His broad smile said that his connection to Buddhism remains alive and joyful.