The Taming of the Demons: Violence and Liberation in Tibetan Buddhism

By Jacob P. Dalton

Yale University Press, 2011, $40; 336 pages

Reviewed by Rory Lindsay

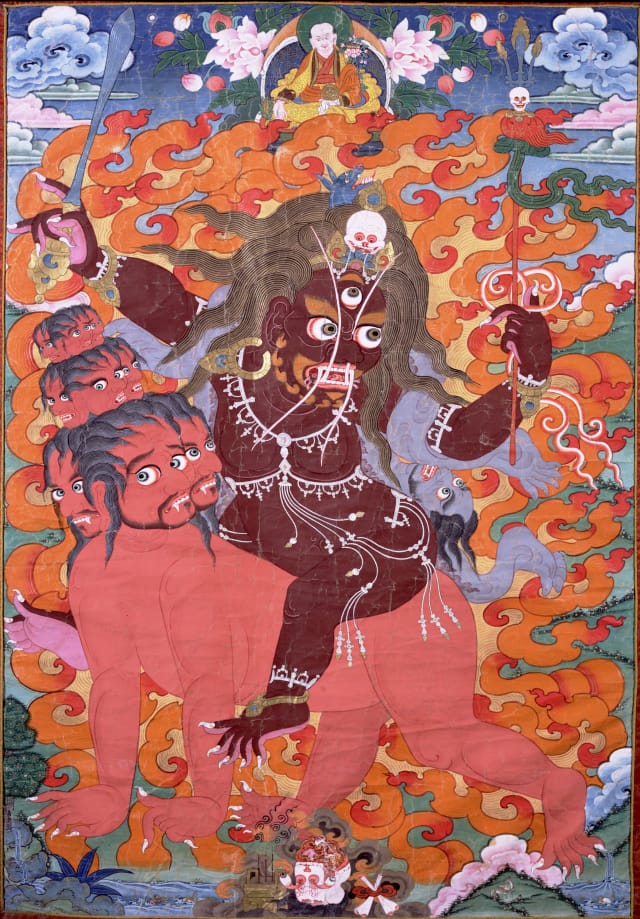

There once stood a buddha coated in spiders, scorpions, and snakes. He had nine vile heads, enormous wings, eighteen hands clasping fearsome instruments, and spat fire as he trampled the beings underneath him. The perfection of compassion, he forced a trident into the torso of a ruthless demon named Rudra—a formerly devout Buddhist who became an enemy of the dharma after misunderstanding key doctrines—and consumed him, thereby ending his awful career. In the buddha’s stomach Rudra was purified, and after emerging from the buddha’s anus, he pledged allegiance to him and begged for liberation. The buddha offered teachings before finally destroying him, liberating him into emptiness and reconstituting him as a protector of the dharma.

Told and retold in various tantric Buddhist sources, this narrative has long served to justify the tantras’ insistence on compassionate violence as a path to liberation. Violent ritual, Buddhists have reasoned, became necessary when Rudra emerged as a powerful demonic force. The longest extant version of the story is found in the Compendium of Intentions Sutra, a central work of the Anuyoga class of tantras belonging to the Nyingma, or “Ancient,” school of Tibetan Buddhism. In his new book, The Taming of the Demons, Nyingma specialist Jacob Dalton takes this text as his starting point, building around it a fascinating history of violence in Tibetan Buddhism.

Associated with the Rudra myth are numerous ritual manuals. Mimicking Rudra’s liberation at the hands of a buddha, these works identify the steps for conducting the ritual murder of those who threaten the dharma. While nearly all of these manuals recommend an effigy of paper, cloth, or dough, Dalton finds instructions in a tenth-century Tibetan manuscript from the famous “library cave” at Dunhuang that suggest the involvement of a live victim. First, the text lacks a summoning rite, by which one draws the victim’s consciousness to the effigy. It also describes lobbing the victim’s severed head onto a mandala, and then divining his or her next rebirth based on the head’s position, explaining that if it splits open, the rebirth will be favorable. Such a rite, Dalton argues, demands a three-dimensional effigy that is capable of splitting apart. Another text from Dunhuang even identifies both the victim’s head and blood as offerings.

Yet, as Dalton carefully notes, none of this guarantees that living victims were targeted in the performance of these rituals. The use of three-dimensional dough effigies is common in Tibetan Buddhism, and some of these effigies even contain hidden pouches of blood.Similarly, these texts may have guided only imagined ritual practices, in which the meditator performs the offerings in his or her mind. Add to this a lack of archaeological evidence and the matter becomes highly ambiguous, resisting attempts at conclusive historical assessment.

Discussions of human sacrifice are not confined to the ritual manuals, however. Dalton turns to the writings of King Yeshe Ö (947–1024), who issued a public edict commanding the tantrikas of Tibet to desist from “liberating” people alive. Yeshe Ö laments that while the great kings of Tibet’s imperial period—Songtsen Gampo (circa 605–649/650) and Trisong Detsen (circa 742–800) among them—had successfully halted blood sacrifices, these rites had resurfaced during the century and a half of political tumult and lawlessness preceding him.

Yeshe Ö’s edict is striking in its mention of human victims. Yet Dalton is careful here too, situating the proclamation in its legal and political context. At the time of Yeshe Ö’s reign, local chieftains styled themselves as the inheritors of both clan power and tantric lineages, associating with practitioners of various tantric traditions. Seeking political dominance, Yeshe Ö aimed to unite these chieftains and tantrikas under a single Buddhist law, declaring Buddhism the state religion, devising a sophisticated legal system, and calling for a return to institutional monasticism and more conventional Buddhist ethics. He chastised tantrikas who ate meat, drank alcohol, had sex, frequented cemeteries, and offered flesh to the buddhas, along with the chieftains who had allowed such behavior to occur. To him, these individuals had misunderstood the Buddhist teachings, taking them literally while deeper, symbolic meanings were available. Certainly, Yeshe Ö did not seek to suppress the tantras entirely, but rather to domesticate their practice, dubbing “liberation” rites involving effigies Buddhist, and “sacrifices” involving live victims demonic. While Dalton does not believe Yeshe Ö’s edict reflects pure self-serving political expediency—it is possible that Yeshe Ö is responding to real murderous undertakings—his criticism of tantric violence worked to justify the rational rule of law, highlighting the consequences of the chieftains’ approaches to governance.

A more recent Tibetan work by the Nyingma author Rigdzin Garwang (1858–1930) echoes the violent implications of Yeshe Ö’s edict. At around the time that L. Austine Waddell (1854–1938) was writing The Buddhism of Tibet or Lamaism, the first detailed study of Tibetan Buddhism to appear in English, Garwang was composing a text titled The Dangers of Blood Sacrifice. Unaware of each other, these two men shared similar attitudes toward violence and societal reform in Tibet. Waddell, on the one hand, criticized Tibetans for defiling true Buddhism with their sorcerous, violent ways, and prayed that his fellow British colonialists would one day liberate them from their lamaist overlords. Garwang, on the other hand, addressed his fellow citizens of Nyarong, a remote region on the border between Tibet and China, who had only recently adopted the traditions of institutional Buddhism. He admonished those performing perverse blood sacrifices, and demanded observance of Buddhism’s more conventional ethical ideals. While declaring that Indian Hindus, Tibetan Bönpos, and certain Buddhists clearly had it wrong, he did not recommend forgoing such rituals altogether. Rather, he suggested that an authentic Buddhist practitioner could perform a liberation rite without anger, delivering the victim’s consciousness into a pure buddhafield before restoring the sentient being who had been killed. As Dalton observes, this remarkable procedure departs from Yeshe Ö’s edict, blurring the distinction between “sacrifice” and “liberation.” Yet it also, in his estimation, points to a context very similar to Yeshe Ö’s, namely, a Tibet in which blood sacrifices were actually performed.

Aside from questions of blood sacrifice’s historical reality in Tibet, Yeshe Ö and Garwang’s texts also raise questions about what counts as Buddhist. As Dalton notes, it is tempting to describe the Dunhuang liberation rite as an example of Buddhist human sacrifice, but many Buddhists would regard the coupling of the terms “Buddhist” and “human sacrifice” as oxymoronic. The majority of ritual manuals demand the use of an effigy, and numerous Buddhist texts, including the Buddhacarita, an early Indian biography of the Buddha, describe the Buddha’s rejection of violent Vedic sacrifice. Tibetan histories such as the Sayings of Ba, moreover, describe Buddhists condemning Tibetans’ pre-Buddhist practice of ritualized killings. Such condemnations, Dalton explains, continued until Garwang’s day, with numerous lamas denouncing the use of ritual violence. Whether in each case they were responding to flesh-and-blood tantrikas to whom institutional Buddhism seemed overly sanitized or, rather, the mere possibility that certain practitioners might take the tantras literally is difficult to determine. Either way, though, their writings can be seen as efforts to define the boundaries of Buddhist practice in the face of cryptic and authoritative tantric literature, the difficulty of which cannot be overestimated.

These are only some of the issues that The Taming of the Demons so skillfully illuminates. Much more could—and indeed should—be said about this outstanding book. Dalton treats a variety of other violent matters, from early Buddhist scriptural allowances for murder, to the employment of Buddhist rituals of warfare by both “the Mongol Repeller” Sokdokpa (1552–1624) and the Great Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682). Equally compelling is his discussion of violent mythology’s role in the construction of temples and the mapping of Tibet’s geography. Each chapter, in short, offers important insights into violence’s place in Tibetan Buddhism, resulting in a rewarding read for those willing to confront Tibet’s darker facets.