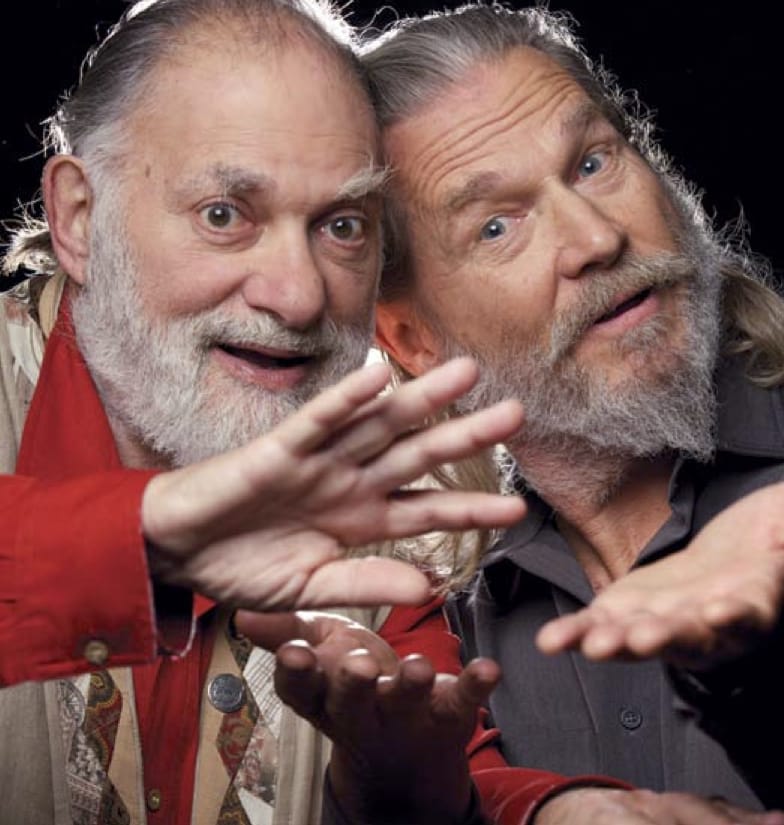

Now a slice of their freewheeling exchange has been published in book form as The Dude and the Zen Master.

To talk about this new release, I requested an interview and today is the day. The three of us are settling into a corner of the lounge at New York’s Four Seasons Hotel and Bridges is asking if photos will be taken during our conversation. If so, he wants to set a good example and put away the water bottles an assistant has provided for us. “I’m trying to get off these plastic things,” he says. Three water goblets quickly appear on our table, plus a danish and coffee with milk for Glassman and, for Bridges, tuna tartare, which is prettily served with pine nuts and chilies. As for me, I resist the urge to bring up white Russians—the drink of choice for the Dude, the character Bridges played in The Big Lebowski and for which he’s earned a cult following.

When I ask Glassman what initially drew him to Bridges, he says, “Jeff is well-known, but he’s just a regular guy. He’s not somebody who makes himself out to be more special than anybody else. He’s interested in serious subjects. He’s comical and open. A lot of people only want to talk about their thing, in their way, whether it’s the liberal cause is the only cause, or some other cause is the only cause, or you’ve got to be Buddhist or you’ve got to be Zen or Tibetan. Everybody’s got so many fixed opinions— opinions they fixate on. I found Jeff to be much more open.” For his part, bridges says he was drawn to Glassman from the get-go because he defied his expectations of a Zen master. With him there was no formality, no big deal.

Before Bernie Glassman was a Zen master, he was an engineer and mathematician working in the aerospace industry. As he sees it, it was not a big leap from that field to Zen, because Zen is all of life. In everything we do, we can bring to bear what, in The Dude and the Zen Master, he calls “the Zen of action, of living freely in the world without causing harm, of relieving our own suffering and the suffering of others.”

Glassman did his Zen training with the legendary Zen master Maezumi Roshi, who played an instrumental role in establishing genuine Zen in the West. They met in 1963, when Maezumi was a young monk assisting an old roshi at a Zen temple in little Tokyo, Los Angeles. Glassman asked the old roshi why they punctuated their sitting practice with walking meditation. But the roshi’s English was poor, so he indicated that Maezumi should respond. “When we walk, we just walk,” was all Maezumi said. That, according to Glassman, was the beginning: he wanted to “hang with this guy.”

A few years later Glassman was Maezumi Roshi’s right-hand man and—as Glassman puts it—he was traveling with Maezumi wherever he went and getting to meet “all the old-timers,” the pioneering Buddhist teachers who came West. Glassman chose to stay with Maezumi Roshi because—in his opinion—Maezumi had a very clear understanding of the dharma. “Now,” says Glassman, “I look back and think, who the hell was I at that age to be able to judge who had a clear understanding? It’s more accurate to say that I liked the way he talked about the dharma.”

“Maezumi Roshi was in a way a very soft person and in a way a very dogmatic person,” Glassman continues. “In our private studies, he’d always tell me that he was Japanese and could not make an American Zen. But he could help me grasp the essence of Zen and I should swallow it all up and then spit out what didn’t work for me. In fact, when I was ready to go start my own center, he said, ‘I’ll stay away for a year because I don’t want to influence you.’” Maezumi’s desire for Glassman to create his own way stood in curious contrast to his rigid emphasis on linear hierarchy. The teacher-student relationship is clearly defined in traditional Japanese culture, says Glassman. “You can’t be a friend to somebody who’s studying with you.” So his relationship with Maezumi was imbued with this formality. “At the same time,” asserts Glassman, “we were so close that the boundary moved,” even though the words didn’t. Glassman still remembers when Maezumi told him that he was planning to make him a roshi, and Glassman said he didn’t want to use that title. “What do you mean?” asked Maezumi. “What do you want to use?” Bernie, just Bernie, was the answer. But that was a no-go for Maezumi, so Glassman relented: “Roshi” would be fine. “I couldn’t have hair when I was with Maezumi roshi and I couldn’t be Bernie,” says Glassman. “Then he died in ’95, and by ’96 I was Bernie again, and I had a beard and hair.” For Glassman, this marked a shift away from the traditional, linear hierarchy of student and teacher. maybe he’s a little further along on the path than his students, but he believes that—hanging with them—they’re all learning together.

Jeff Bridges played his first film role when he was six months old, an uncredited part in the 1951 release The Company She Keeps. By nature he was a happy baby, but his part required him to cry. “Just give him a little pinch,” his mother suggested. “So that,” Bridges laughs, “was the beginning of my acting career.”

Bridges describes himself as “Buddhistly bent.” As often as he can, he does sitting meditation for twenty minutes in the mornings and he reads the dharma, especially the teachings of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Pema Chödrön. He says he’s particularly into lojong, a Mahayana system of mind training, and is curious about the Kagyu lineage of Vajrayana Buddhism, sometimes called “the mishap lineage” and renowned for some outrageous characters who rejected the saintly stereotypes. Paraphrasing Pema Chödrön, Bridges says that “when you pay homage to these cats, whom people could think of as very flawed,” you’re paying homage to that side of yourself as well, accepting the full package of who you are. Like all of us, they started out as confused, mixed-up people, and yet—by never giving up on themselves—they ultimately discovered their own genuine quality, their buddhanature.

According to Bridges, when he meditates he often makes small adjustments to get back into the space of simply being, and as an actor he does the same thing. He plays a scene one way, then another, and each time he makes an adjustment he clicks into a new space—the space of the present moment.

As a kid, Bridges practiced his acting skills with his father, Lloyd, the well-known star of Sea Hunt, a high-adventure television series that was syndicated for decades. In The Dude and the Zen Master, Bridges recounted, “if we were doing a scene together, he’d say, ‘don’t just wait for my mouth to stop talking before you answer. Listen to what I’m saying and let that inform how you talk back. If I say things one way, you’re going to react one way, and if I say them a different way, you’re going to react a different way.’ Or he’d give me this direction: ‘make it seem like it’s happening for the first time.’ ” In Zen that’s called beginner’s mind.

Recently, Bridges worked on the supernatural cop film R.I.P.D., and just before beginning a scene his costar Kevin Bacon would state gravely: “Remember, everything depends on this!” because the filming was so clearly not a life-and-death situation, this would make everyone laugh and peel away the tension. But, according to Bridges, there was a grain of truth in what Bacon said. in a sense, everything does depend on just this moment.

Bridges’ late mother, Dorothy Bridges (née Simpson), played a great role in informing his spirituality. While he was growing up, she had him and his siblings read The Daily Word over breakfast. These teachings come from the contemplative Christian tradition, but when she was around ninety years old, she turned to Buddhism, and Bridges remembers taking her to a Buddhist talk. After the teacher had finished speaking he invited questions, and Dorothy raised her hand. “Words, words, words!” she shouted when she was called upon. “Yes, exactly,” the teacher responded.

But Dorothy had a lifelong passion for words, both reading them and writing them. Once, when asked if there was anyone she’d ever been in love with before her husband, she sighed, “Only my English teachers.”

Lloyd and Dorothy’s first child, Beau, was born two days after pearl Harbor and had to be delivered by candlelight because of a power blackout. In 1948, Garrett followed, but when he was less than two months old, he died of sudden infant death syndrome. According to Dorothy, it’s commonly believed that children are our immortality, but they’re really closer to our mortality; we love our children more than we love ourselves and yet we can find ourselves powerless to protect them. Nonetheless, she and her husband went on to have two more children: Jeff, born in 1949, and Lucinda, born six years later.

Young Jeff sometimes appeared in Sea Hunt, and one day he was on the set when a director yelled at an underling. Bridges says, “My dad went up to the director and very calmly said to him, ‘I’m going to be in my dressing room in my trailer. When you’re ready to apologize to this guy in front of all of the rest of us, that’s where you’ll find me.’ So the guy had to apologize.”

The young Bridges was mortified, yet ultimately grew up to admire his father’s sense of justice and love of acting. “He really enjoyed the communal aspect of everybody working together to pull off a kind of magic trick,” Bridges says. “He would create a joyful atmosphere that was contagious. That relaxed people, and out of relaxation comes the cool stuff. A lot of folks in showbiz don’t want their kids to go into it because it’s got a dark side. But my dad encouraged all of us. He would say to me, ‘Jeff, do you want to come to work with dad? Come on, you’ll get out of school! You can make some money, buy some toys!’”

Bridges, however, resisted becoming an actor; it felt to him like nepotism. He wanted to be appreciated for his own talents, not because his famous father was opening doors for him. Yet there was nothing to worry about. With the release of Peter Bogdanovich’s seminal 1971 film, The Last Picture Show, everyone knew that Jeff Bridges was a talent in his own right. He earned his first Oscar nomination for his role and ever since he’s had a steady career, playing in one or more movies most years and earning five more Oscar nominations. He was up for Best Supporting Actor for both 1974’s Thunderbolt and Lightfoot and 2000’s The Contender, while 1984’s Starman, 2009’s Crazy Heart, and 2010’s True Grit got him nominated for best actor. many people consider his win for Crazy Heart to be a long-overdue acknowledgement of his remarkable career.

I was on the subway in New York, preparing for my Bridges and Glassman interview by reading The Big Lebowski and Philosophy, which is part of the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop-Culture series. Suddenly, the guy sitting beside me noticed my book. “Oh, my God, I love that movie,” he exclaimed. “I’ve watched it, like, thirty times!” He then went on to tell me that back in college, he and his friends had what they’d called “The Lebowski Challenge.” Participants would watch the movie and every time a character drank a white Russian, they had to down one, and every a time a character smoked a joint, they also had to light up. “Nobody ever made it through,” my fellow traveler admitted. Before the final credits rolled, all participants had either passed out or puked. Or both.

From my point of view, any film that could have inspired this drinking/drugging game is an unlikely candidate to be a Buddhist cinematic classic. Nonetheless, in certain circles The Big Lebowski is celebrated for its dharmic wisdom. Maybe this shouldn’t strike me as strange. While puritans like me abound, Buddhist history is peppered with practitioners on the wild side. In the Tibetan tradition, there is the mishap lineage that Jeff Bridges is so fascinated by, and in the Zen world there are such iconoclastic figures as the monk Ikkyu, who not only drank heavily but also apparently visited brothels wearing his robes because he believed sexual intercourse was a religious rite.

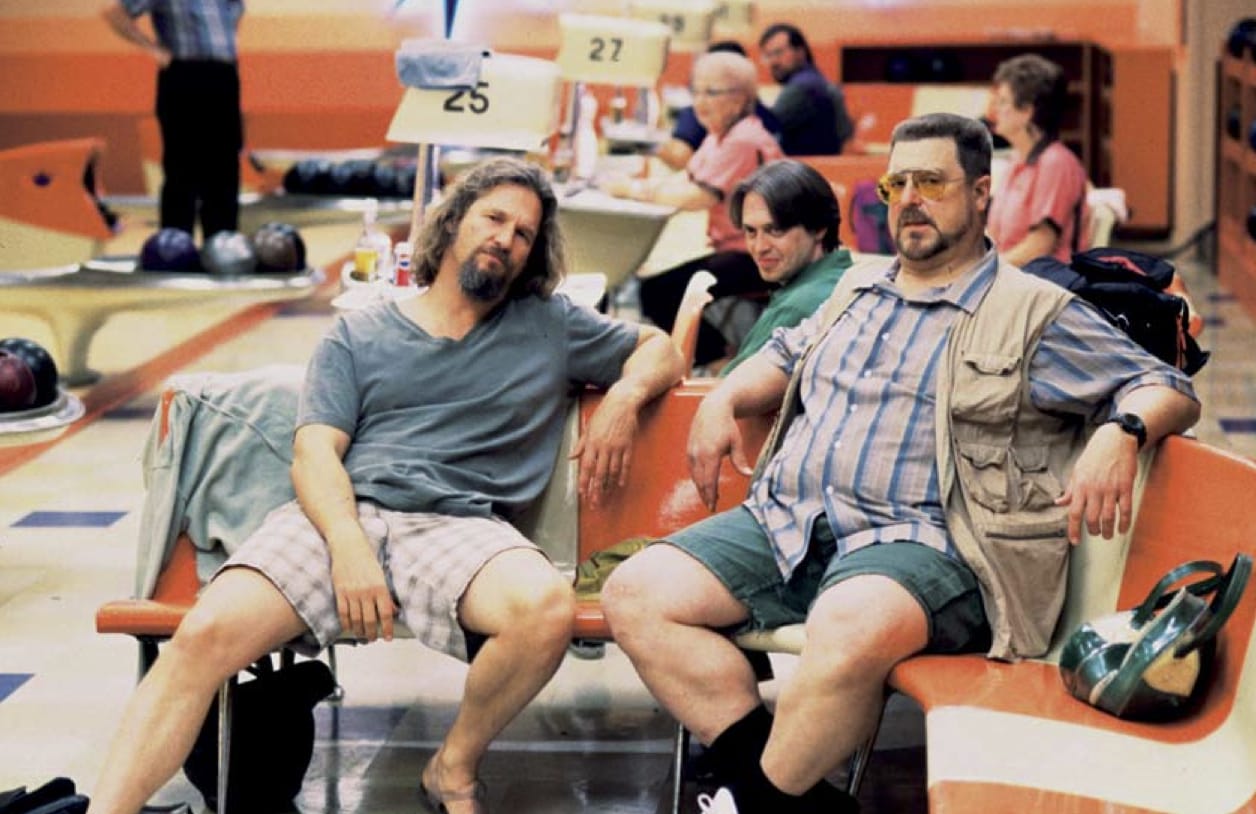

Bridges was skeptical when Glassman first told him that many people consider the dude to be a Zen master. During the making of the film, no one claimed any such thing—neither the actors nor the film’s creators, the renowned Coen brothers, Joel and Ethan.

Glassman laughed. “Just look at their name—the Koan brothers.” He went on to assert that The Big Lebowski is filled with modern-day koans: “The Dude abides—very Zen, man. Or The Dude is not in—classic Zen.”

According to Merriam-Webster, to abide means to wait, to endure without yielding, to bear patiently, to accept without objection. “That is no easy feat, especially in a culture that is success-driven, instant-gratification-oriented, and impatient, like ours,” Bridges says in The Dude and the Zen Master. “True abiding is a spiritual gift that requires great mastery. The moral of the story, for me, is: be kind.”

Yet the dude isn’t some idealized bodhisattva. As Glassman points out, he’s “a lot like us. Stuff upsets him, like when some- one pees on his rug. He has thoughts, frustrations, and every- thing that we all have, but he doesn’t work from them. He works from where he is.”

That is, the dude is authentic. When he gets bent out of shape, he doesn’t feign tranquility but quickly readjusts to his new circumstances, showing that he isn’t attached to a self-image or identity. “Since he abides nowhere,” continues Glassman, “he is free to abide everywhere.”

In stark contrast is Walter, the dude’s bowling buddy played by John Goodman. Walter suffers intensely because he can’t accept that in life there are strikes and gutters, ups and downs. In Walter’s own words, “This won’t stand, man.” He’s attached to his opinions and, because his opinions are so odd, so extreme, and so blatantly untrue, he helps us see the holes in all opinions, even our own. Even when we think our opinions are sacred.

“A lot of people say that my boss, this guy Shakyamuni Buddha, talked about the four noble truths,” Glassman ribs. “But what he really taught was ‘the four noble opinions.’” We can’t say that Buddhism is about not being attached to any truth, and then say there are four noble big ones. “There’s a little contradiction there,” says Glassman.

He then claims that, in constantly telling Donny to “Shut the fuck up,” Walter is employing a standard Zen technique for relaxing opinions. It’s in the same spirit as the Zen teacher Ummon striking his student Tozan for saying innocuous things, as recorded in the classic koan Tozan’s Sixty blows. Zen masters of this rough ilk, says Glassman, are “trying to get you to realize that what you’re saying ain’t the truth. It ain’t the whole thing.” in fact, “There ain’t no whole thing. You’ve got to just be open.”

Or as the dude says, “That’s just like your opinion, man.”

So now for my opinion about The Big Lebowski and its dharmic thread. As I see it, the dude indeed abides in a way that smells faintly of spirituality. Though I detect attachment to a certain sweet, milky cocktail, he’s essentially unattached to material goods. If his dumpy apartment doesn’t tip you off to this, you can see it in the understated way he describes losing a million dollars: “Lost a little money today.”

By and large the Dude is also compassionate, thinking as he does about the safety of Bunny. But he’s clearly fast and loose with the precepts. Beyond the aforementioned cocktails, he’s not above a lie or two—if it means getting his soiled rug replaced. Moreover, he doesn’t really practice the Zen ideal of effortless effort. Unemployed and smoking up in his bathtub while listening to whale music, the dude is simply effortless. Right from the beginning, the Stranger who bookends the film tells it to us straight: the Dude “is a lazy man…quite possibly the laziest in Los Angeles county, which would place him high in the runnin’ for the laziest worldwide.” Don’t think, though, that I don’t have a soft spot for the dude and his easygoing ways. It’s just that, instead of lumping him into the Buddhist tradition, I think he merits his own, all-American religion. And, indeed, he has inspired one. It’s called dudeism and, if Dudeism.com is to be taken seriously, it boasts over 150,000 ordained priests worldwide. The home page offers this invitation: “Come join the slowest-growing religion in the world…an ancient philosophy that preaches non-preachiness, practices as little as possible, and above all, uh…lost my train of thought there.”

The Hebrew word for peace is shalom, and to Roshi Bernie Glassman it’s the key to his work with the Zen Peacemakers. It’s a word many people are familiar with, but what’s less commonly known is that the root of shalom is shalem, meaning whole. Therefore, to make peace is to make whole, and in Zen—according to Glassman—the practice is to realize the wholeness and interconnectedness of life.

Glassman had a profound experience of wholeness in the early seventies, shortly after finishing his mathematics Ph.D. He was driving to work one morning when he had a vision of hungry ghosts everywhere. Called pretas in Buddhist cosmology, these are beings who experience (and represent) endless and unfulfillable desire. At first he saw these hankering, unsatisfied beings as existing outside himself. But suddenly he had the keen sense that there was no separation: he was those beings, they were him. Glassman knew then that his life’s calling was to feed the hungry, literally and figuratively. He would not stay forever holed up in a zendo but would take the realizations won on the cushion out into the world.

In 1982, Glassman and his students opened the Greyston Bakery in Yonkers, New York, a city then plagued by unemployment, violence, and drugs. His vision was that a business could have a double bottom line; it could both generate profits and serve the community. On the ground this meant hiring people who would conventionally be considered unemployable. But—contrary to what some might expect—this was no recipe for disaster. In fact, Greyston was soon baking cakes and tarts for some of the most exclusive eateries in New York and making brownies for Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. Today, the bakery is a solid $6 million business with over 75 employees.

And it’s just one piece of a larger socially responsible business model. What has become known as the Greyston Foundation also includes the Greyston Family Inn, the Maitri Center, and Issan House. The Greyston Family inn offers hundreds of low-cost permanent apartments for homeless families and a child-care center, after-school programs, and tenant-support services. Maitri is a medical center that serves people with AIDS-related illnesses, and Issan House provides housing for many of Maitri’s patients.

in 1994, on Glassman’s fifty-fifth birthday, he decided to establish the Zen Peacemakers Order. Originally, it was intended strictly for Zen practitioners, but it eventually blossomed into an international, interfaith network. As articulated by Glassman, the community is founded on three tenets for integrating spiritual practice and social action: (1) not-knowing, thereby giving up fixed ideas about ourselves and the universe, (2) bearing witness to the joy and suffering of the world, and (3) loving action for ourselves and others.

Glassman sees these three tenets as the essence of Zen, phrased in a fresh, modern idiom. “In Zen training,” says Glassman, “koan study gets you to experience the state of not knowing.” Then bearing witness is just sitting, or shikantaza, and loving action is none other than compassion.

In terms of peace and justice work, Glassman explains the three tenets by saying that positive change doesn’t come out of an activist having fixed ideas. What really helps is being completely open and listening deeply. “I try to become the situation,” he says, “and then I let the actions come out of that.”

Bearing witness is at the heart of the groundbreaking retreats for which Glassman has become best known: street retreats and retreats held at the concentration camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Street retreats combine meditation with living as a homeless person for several days, with no money, no shelter, no job, no usual identity. Retreatants take their meals in soup kitchens and learn to survive without even the guarantee of a bathroom. Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, a Buddhist teacher who was given dharma transmission by Glassman, has said that the power of a street retreat lies in how it pushes things “right in your face…so there is no way to exclude anything. Living on the street is scary. But the minute you include the fear in your practice, it’s much less scary because then the fear is there. You can touch it, you can feel it, and it’s not this black cloud that’s following you around.”

During the bearing-witness retreats at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the lion’s share of each day is spent sitting by the infamous train tracks, alternating silence with chanting the names of the victims. Glassman was originally inspired to hold these retreats when he went to Auschwitz for an interfaith conference.

“I walked into Birkenau,” he told me, and “I could feel the millions of souls crying out to be remembered. I said I have got to bear witness to what’s going on here. I spent a year and a half creating a format, which involved bringing together people from all walks of life—children and grandchildren of SS members, survivors, children of survivors, people from many countries, many religions.” This November will mark the eighteenth annual retreat memorializing the Holocaust. Then Glassman will lead a Rwandan retreat in April 2014, bearing witness to the twentieth anniversary of the genocide there.

Their mutual commitment to social action is a big connection between Bernie Glassman and Jeff Bridges. Stamping out hunger is Bridges’ main focus, and he has been dedicated to it for almost as long as he’s been in film. A cofounder of the End Hunger network, he is also the national spokesman for Share Our Strength’s No Kid Hungry campaign; in the capacity of this role, he was invited to speak to both Republican and Democratic governors at last year’s political conventions.

You might think that such a speech would be no big deal for an actor, but Bridges tied himself up in knots over it. It was four pages long, and he painstakingly memorized every word of it as though it were a monologue. Yet he was keenly aware that a speech is not a movie. There would not be take after take until he got it right—this was a one-shot deal, and the stakes were high. It was imperative that he impress upon both Republican and Democratic governors that childhood hunger is an issue that should transcend the political divide.

As it turned out, nothing was what Bridges expected. The first surprise was that his speech to the Republican governors was scheduled for the peculiar hour of 10:30 p.m. The second surprise was that he would have to compete with booze and bowling pins; that is, his speech was to be delivered first in a bar and then repeated a little later in a bowling alley. To make matters worse, the 10:30 speech got postponed to eleven, then midnight, and finally it got rolled into the one at the bowling alley.

“Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell, who is chairman of the Republican Governors Association and already part of the No Kid Hungry campaign, arrives, gives me a wonderful introduction, and splits,” Bridges recounts in The Dude and the Zen Master. “It turns out that there are no other governors there at all. I end up giving the talk I’d agonized over for two months to an audience of seventy-five college girls at the bowling-alley bar. And I don’t change a thing, either. I memorized my lines so well that I just give the entire four-page speech written for state governors—I hope you’ll join Governor McDonnell and others to develop state solutions to childhood hunger—to a bunch of college girls.”

Not that Bridges is putting these young girls down. He’s quick to add that—you never know—one fine day it just might be one of those girls who really makes a difference.

At the Four Seasons lounge, Bernie Glassman clarifies that the koans in The Big Lebowski are “not from Jeff,” but rather from the Coen Brothers’ script. “Jeff just happens to be the guy who is the dude in the movie, and he’s also the Dude in his life.” I think Glassman means that, although Bridges isn’t exactly the dude you see in the film, he isn’t exactly not that dude either. The ways in which he is un-dude are easy to pinpoint. Bridges, for instance, is no perennial bachelor. He’s been married to the same woman for thirty-five years and they have three grown daughters. Nonetheless Bridges has a duderino flavor—he’s chilled out and, for lack of a better word, really nice. Frequently when someone asks him for an autograph, he goes five steps further and offers them a drawing instead. Also like the Dude, Bridges’ speech is garnished with f-bombs and mans, but maybe he and Glassman are just hamming it up for the press. Bridges’ tuna tartare is gone and Glassman’s danish is slightly picked over when the publicist approaches the table. It seems that Bridges’ makeup artist and the rest of the bromantic couple’s entourage are already anticipating the next media event, this one on TV. “Five more minutes,” says the publicist.

Bridges screws up his face. “Cool, cool, yeah,” he says, “but we were just getting going here!”