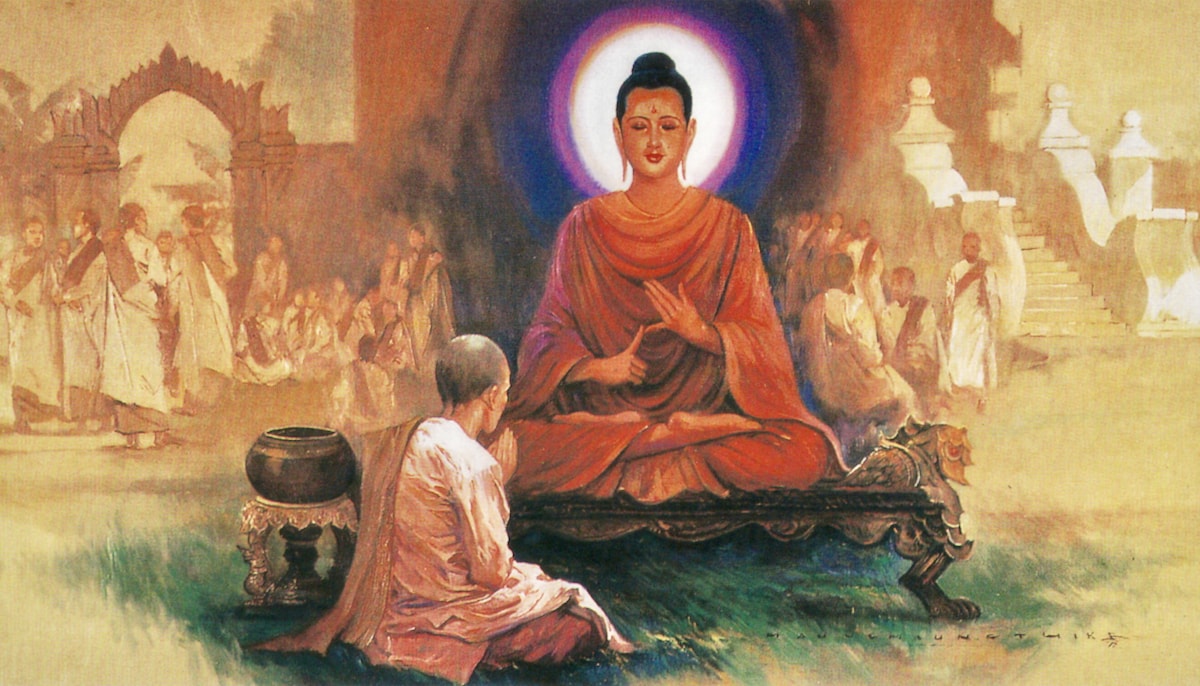

Although the Buddha had female students during the early years of his teaching, there was not a monastic order for women. In India at that time, women were not allowed to participate in the dominant religious framework, where religious leaders were all men. However, five years after his enlightenment, one of the Buddha’s female followers led a group of women in requesting a place for women in the community of home-leaving spiritual seekers.

One female student, Mahapajapati Gotami, was also the Buddha’s aunt and the caregiver who had raised him after his mother died. With a motivation to develop spiritually to her fullest capacity, she repeatedly entreated the Buddha to establish an order of nuns, eventually marching, along with five hundred other women, to make this request. This was the first women’s rights march in recorded history.

Spiritual liberation and social action can go hand in hand.

The Buddha agreed that women were fully capable of fulfilling the path of awakening, and the order of nuns was formed. Thus, the Buddha, together with Mahapajapati Gotami and five hundred other women, set a precedent for the social equality and inclusivity of women. Within its social context, this was a bold and radical action. Many of those women are remembered today as exemplars of spiritual attainment. These women not only sought spiritual liberation but also forged an alternative life path for themselves that went beyond the social scripts society had allotted them.

Spiritual liberation and social action can go hand in hand. In fact, I would venture to suggest that they always do. We cannot wake up fully without also working toward the awakening of others. To erect an artificial divide between spiritual and social change requires a denial of interdependence. Even if we renounce the world and leave society to be a homeless wanderer in the woods, society is changed by our absence from it. Spiritual and social change are connected, even when we don’t deliberately seek to make it so. Our liberation is bound up with that of others—this is the heart of the bodhisattva path.

This article is excerpted from a longer post, “The Power of Buddhism.”