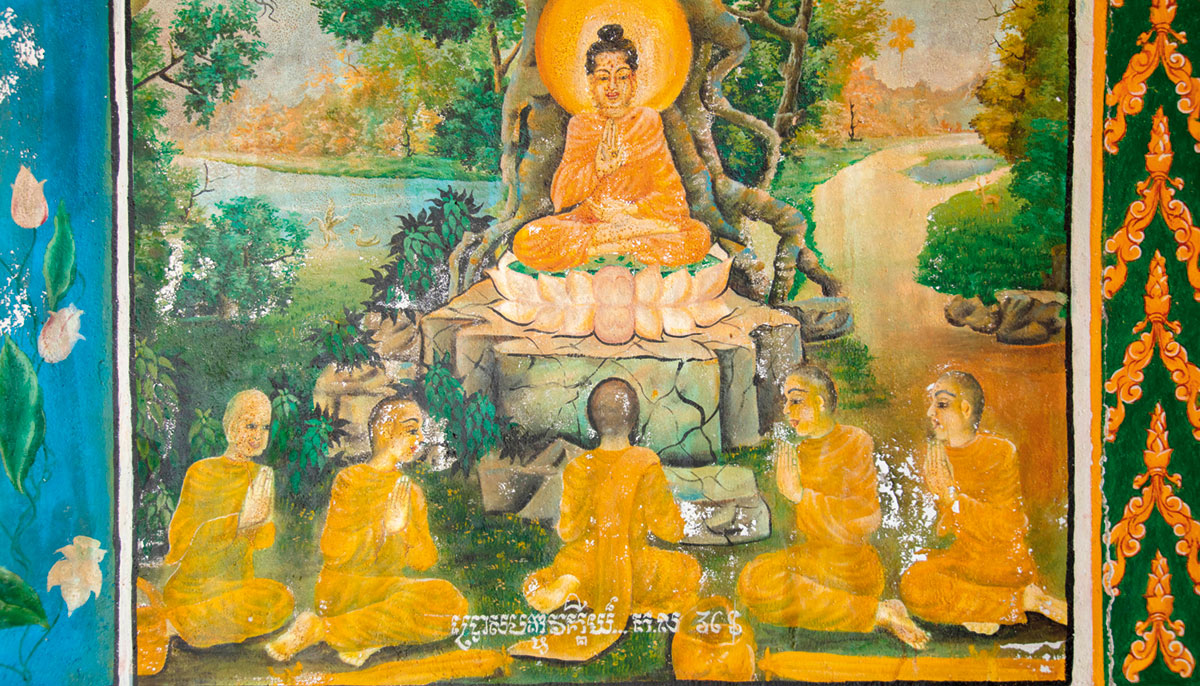

In these uncharted days of Covid-19, it seems appropriate to consider the metaphor of the Buddha as physician.

As a physician of the human condition, the Buddha provided us with a diagnosis of our suffering (the first noble truth) and an etiology, or cause, of our suffering (the second noble truth). Then he gave us a prognosis for our dis-ease (nirvana, the third noble truth) and finally a prescription for the necessary treatment (the fourth noble truth, the path).

The four noble truths are a plan of action, not simply a collection of ideas to be pondered. In the Buddha’s “First Discourse,” there is a specific action enjoined upon us to go with each of the truths.

Regarding the first noble truth of suffering, we are told to understand it, fully: “This suffering, as a noble truth, should be fully understood,” said the Buddha. And, likewise, with the other three:

“This origin of suffering, as a noble truth, should be abandoned.”

“This cessation of suffering, as a noble truth, should be realized directly.”

“This path leading to the cessation of suffering, as a noble truth, should be followed (cultivated).”

Of course, to be fully cured we must actually take the medicine, for as Shantideva noted in his eighth-century classic Way of the Bodhisattva, “What invalid in need of medicine ignored his doctor’s words and regained his health?”

We all wish to be happy and to avoid suffering. Our problem is that we continually seek happiness in the wrong ways and, as a consequence, we only experience more suffering. How can we break the cycle? First, we need to understand more fully and completely our suffering.

According to Buddhism, there are actually three distinct kinds of suffering. First, there is suffering plain and simple (dukkha-dukkha). In this particular kind of suffering, Buddhism includes both physical and mental suffering—everything from a mosquito’s hum to an arrow in the eye, everything from the subtle trauma of experiencing a pandemic to the grief of losing a loved one.

Second, there is the suffering of change (viparinama-dukkha), as when happy times quickly change to unhappy ones. For example, we are having a great time at the party, but then the clock strikes midnight, and the party’s over! Or we’re heading out for a trip in the car. It’s loaded up, everything is locked and secured, and then we realize that we’ve locked the keys inside! In these moments, when happiness turns quickly into suffering, there is the suffering of change.

Finally, there is the suffering that is simply inherent in samsara as long as we are stuck in it (samkhara-dukkha). In our ignorance, we want things to remain fixed, but it is in the nature of things in samsara to change. So when changes inevitably occur, we experience suffering. Also, we are continuously, though sometimes only subtly, wishing that things be otherwise than they are. When we can see these patterns, and thus understand our suffering, we can begin to lessen their hold on us.

The second noble truth identifies the causes of our suffering. The Buddha pronounces that its etiology is desire and craving. Our most basic and deep-seated craving is, as mentioned above, that things be different than what they are. If we were truly happy and content, would we wish that things were otherwise?

The action enjoined upon us here is straightforward, though stark. We are told, “Abandon desire and craving! Destroy it!” Not easy. We can all see that this one takes practice! Desire is the fuel that keeps the wheel of samsara turning. We must take the fuel away to stop the engine of the wheel.

But desire is only the most palpable cause; the ultimate cause of suffering is our ignorance, which stems from our clinging to the mistaken conceit of the “I.” We put ourselves above all others. We count ourselves more valuable, more perfect in every way, more important. This conceit—that “I” am better than all others—is our downfall. We cannot escape samsara if we place ourselves above all others. Of course, transforming this deeply entrenched belief is no easy task either. But if we truly wish to be well, this is the cure.

But just when it all seems too hard to do in practice, the Buddha offers a hopeful prognosis. Nirvana, the peace of enlightenment, is there, and it is possible to attain it. The third noble truth tells us that we can attain good health! Our illness can be cured! Our suffering has an end!

All we need to do is follow the noble path, namely, to cultivate and grow our practice. This noble path is sometimes said to consist of 84,000 different methods. Now, nirvana is not a place! Rather, it is simply a view! Remember what the Indian Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna said: “Between samsara and nirvana, there is not the slightest thread of difference.” The only difference is in one’s perception of it. Viewed with attachment, our world of experience is samsara; viewed without such attachment, it

is nirvana.

Even so, and although nirvana is not a place, we can say that the noble path is the way we get there. Over the centuries, as Buddhism has developed and migrated to different countries and cultures, the practices and meditative methods employed to usher in our individual awakenings have been transformed and expanded. Whether we speak of Vipassana, Tantra, Zen, Chan, Won, or Zen Buddhism, all are “paths” showing the way to enlightenment. All are medicines prescribed by the Great Physician, the Buddha. All seek to relieve our suffering. But again, without taking the medicine ourselves we cannot be healed. As Shantideva noted, “What invalid was ever helped, by merely reading in the doctor’s treatises?”

Though varied and multiple, all of these methods in the end come down to being aids to help us to chip away at—until we can completely “abandon” (as the second noble truth tells us to)—our false notion of an independent, inherently existing self, or “I.” Clinging to this false sense of “self” is our basic ignorance, and this ignorance accounts for all of our suffering. Only the wisdom that sees through this ignorance—our erroneous sense of “self”—can ultimately free us.

A simple way of reflecting on the four noble truths is offered by Lama Thubten Yeshe in his book Buddhism in a Nutshell: Essentials for Practice and Study. After calming the breath and setting one’s motivation for practice, one should contemplate as follows:

“Take some time to reflect on each of the four noble truths, one at a time, and see how they relate to your own life. Try to come up with examples where you recognized a suffering situation, determined its cause, concluded it did not have to be that way, and remedied the situation. Finally, make a determination to apply this knowledge to suffering whenever you encounter it.”

At the end of this reflection, we should, of course, dedicate the merit, thinking, “By virtue of this effort, may I quickly generate all the realizations of the path to enlightenment and become a buddha for the benefit of all.”

Opening our minds and our hearts to others without fear, we can experience the happiness and liberation Shantideva wrote about so long ago:

All the joy the world contains

Has come through wishing happiness for others.

While all the misery the world contains

Has come from wanting pleasure for oneself alone.