While he has earned many accolades, ask the Dalai Lama who he is and he’ll offer a modest answer: “I am a simple Buddhist monk, no more, no less.”

His Holiness’ humility is a testament to his uniqueness as a world leader. Despite his global influence and remarkable list of accomplishments, he views himself as just another member of what he calls our “one human family”—a family he cherishes deeply.

The Dalai Lama guides humanity on a path toward peace, his stewardship extending to the protection of our planet. For people across the globe, of every religious tradition, he serves as a radiant beacon of love and fervent advocate for human rights. His Holiness is a light in the darkness of our world, using his voice to teach that anger, violence, and hatred can only breed more of the same. “My religion is very simple,” he has said. “My religion is kindness.”

“The Dalai Lama knows the pain of his people, of humanity, and of the world. But his smile remains.”

As the spiritual head of Tibet, the Dalai Lama embodies the roles of statesman, theologian, and herald of compassion. He’s the foremost leader of the Gelug, or “Yellow Hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism, which is the most prominent of the four main Tibetan Buddhist schools. Moreover, he’s a unifying spiritual figure for all Tibetans, representing Buddhist values and traditions that go beyond sectarian boundaries. Previously, he was also the political head of Tibet.

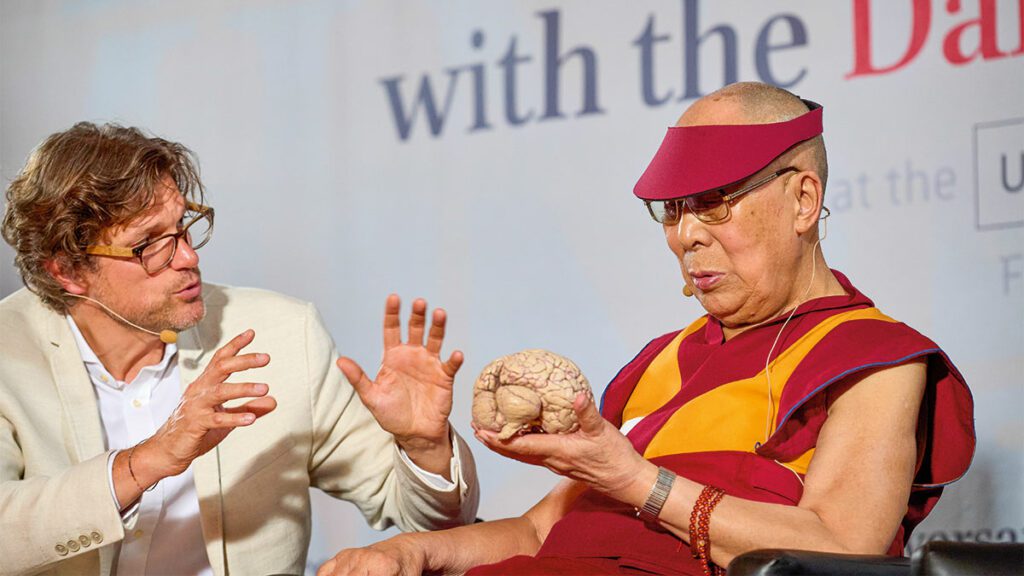

The Dalai Lama also has long had a special interest in science, particularly the science of the mind. He helped found the Mind & Life Institute in 1987, a foundation dedicated to integrating science with contemplative practice and wisdom traditions to better understand the mind. For decades now, he’s maintained numerous personal connections and dialogues with a global community of modern scientists and has encouraged the scientific exploration of Buddhist meditation.

The Dalai Lama we know today is the fourteenth in the succession of Dalai Lamas, a lineage of reincarnated beings considered to be a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. It’s his inherent compassion that has buoyed him through great adversity, landing him on the world stage and inspiring millions to live happier, kinder, more meaningful lives.

My earliest memories of the Dalai Lama date back to childhood, seeing glimpses of a man in red and yellow robes on television while my parents watched the morning news. I recall him shaking hands with various dignitaries, crowds of admirers, and the occasional celebrity.

Alongside his robes and signature eyeglasses, His Holiness always wore a smile that emanated what I now recognize as loving-kindness. Though I knew nothing of his role in the world or the teachings I would one day take to heart, the essence of his character was evident in his very being. It wasn’t until I later read the story of his life and teachings that I began to grasp the depth of his compassion and the resilience behind his smile.

The Dalai Lama was born Lhamo Thondup on July 6, 1935, to a Tibetan farming family in Taktser, a peasant village in northeastern Tibet. He was one of sixteen children born into the family, nine of whom died in infancy. His family farmed buckwheat, barley, and potatoes. As a toddler, he enjoyed collecting eggs with his mother in the family’s chicken coop, sometimes climbing atop a nest and clucking, pretending to be a chicken himself.

Following the death of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, in 1933, the Tibetan government sent out a search party to identify his reincarnation. Led by a series of auspicious signs and visions, the team eventually arrived at Lhamo Thondup’s house. The search team posed as pilgrims, with their leader, Kewtsang Rinpoche, disguised as a servant. He spoke with the boy, who inexplicably recognized him as a lama from Sera, the Rinpoche’s monastery.

Encouraged by the boy’s recognition, the search party left and returned weeks later with a group of dignitaries who performed a series of formal tests they hoped would identify the boy as the reincarnated Dalai Lama. They presented young Lhamo Thondup with a collection of objects, some of which had belonged to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and others which had not. The boy easily recognized the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s possessions, identifying them as his own. Having passed their tests, the search party trusted the boy to be the next Dalai Lama. He was just two years old.

Lhamo Thundop was taken to live at Kumbum Monastery, where he remained for eighteen months due to a ransom requested by the local ruler and warlord, Ma Bufang, who demanded it be paid before the boy could leave for Lhasa. Shortly after his fourth birthday in 1939, Lhamo Thondup finally embarked on a three-month journey to the capital city of Tibet with his family. When Lhamo Thondup was officially enthroned as the reincarnated Dalai Lama in 1940, he was given his spiritual name, Tenzin Gyasto.

At age six, the Dalai Lama began his formal Buddhist education in Tibet, living at the Potala Palace and studying with a series of tutors. There, he spent years learning a variety of subjects, including Buddhist philosophy, Tibetan culture, and Sanskrit, and memorizing Buddhist scripture.

In the 1950s, Eastern Tibet was invaded by Chinese Communist forces. The Dalai Lama, just fifteen years old, assumed his position as the political head of the nation, making him the leader of six million people facing the threat of war. In 1951, he sent a delegation to meet with Chinese Communist leaders in Beijing, and the “Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet” was signed—under duress—surrendering Tibet to Chinese rule. His Holiness traveled to Beijing three years later for peace talks in an effort to create a nonviolent solution with China—to no avail.

In 1959, at age twenty-three, the Dalai Lama took his final exam at Lhasa Johkhang Temple and passed with honors. He was awarded the geshe degree, the highest level of Buddhist education, equivalent to a doctorate of Buddhist philosophy. Meanwhile, it was becoming increasingly clear that the Dalai Lama was in danger of being abducted by the Chinese military, so he and his entourage fled Tibet. He took exile in Dharamshala, India, with tens of thousands of Tibetan refugees following him in the years to come.

In Dharamshala, he established a Tibetan education system and recreated two hundred monasteries and nunneries to preserve the Tibetan way of life in India. The Dalai Lama soon established a Tibetan parliament-in-exile, appealing to the United Nations for the rights of Tibetans, which resulted in three resolutions between 1959 and 1965 that called on China to respect the human rights of Tibetans, all of which were essentially ignored. He opened the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamshala in 1970, which remains one of the most important institutions for Tibetology in the world.

His Holiness took his first foreign trip since his exile in 1967, visiting Japan and Thailand. He has since continued to travel the globe, meeting with other world leaders and dignitaries, always with the goal of promoting peace and drawing awareness to Tibet’s cause, though he has been unable to return home to Tibet, which remains under Chinese rule.

In a 1987 speech at the Congressional Human Rights Caucus in Washington, D.C., His Holiness outlined a five-point plan for Tibet to become a democratic “zone of peace,” which came to be known as the “Strasbourg proposal” after he expanded upon it by proposing the creation of a self-governing Tibet the following year in Strasbourg, France. Though this aspiration has yet to manifest, His Holiness has continued to advocate for the liberation of Tibet.

At fifty-four, he was awarded the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize for his opposition to violence and his determination for the preservation of Tibetan culture through peaceful solutions. “I pray for all of us, oppressor and friend,” the Dalai Lama said in his acceptance speech, “that together we succeed in building a better world through human understanding and love, and that in doing so we may reduce the pain and suffering of all sentient beings.”

I’ve never met the Dalai Lama, and I likely never will, but when I think of who he is to me, I can’t help but to think of him as a friend—someone I know has my best interest in mind. His Holiness trusts in the basic goodness of each of us in this human family. He sees every individual with eyes of compassion, each worthy of love, happiness, and a peaceful life.

Although the Dalai Lama retired from his role as the political head of Tibet in 2011, he remains the spiritual leader of the global Tibetan community. Today, he continues to live in exile in Dharamshala, where he regularly gives teachings and holds important conversations. He has authored over seventy books covering a wide array of subjects reflective of his interests, including science, compassion, nonviolence, and happiness.

The moniker of “Dalai Lama” can be translated to “Ocean of Wisdom.” His Holiness knows the pain of his people, of humanity, and of the world. But his smile remains. He stands tall as a symbol of altruism, love, and compassion—a bodhisattva perfectly poised to lead us beyond the ocean of suffering with his great wisdom.