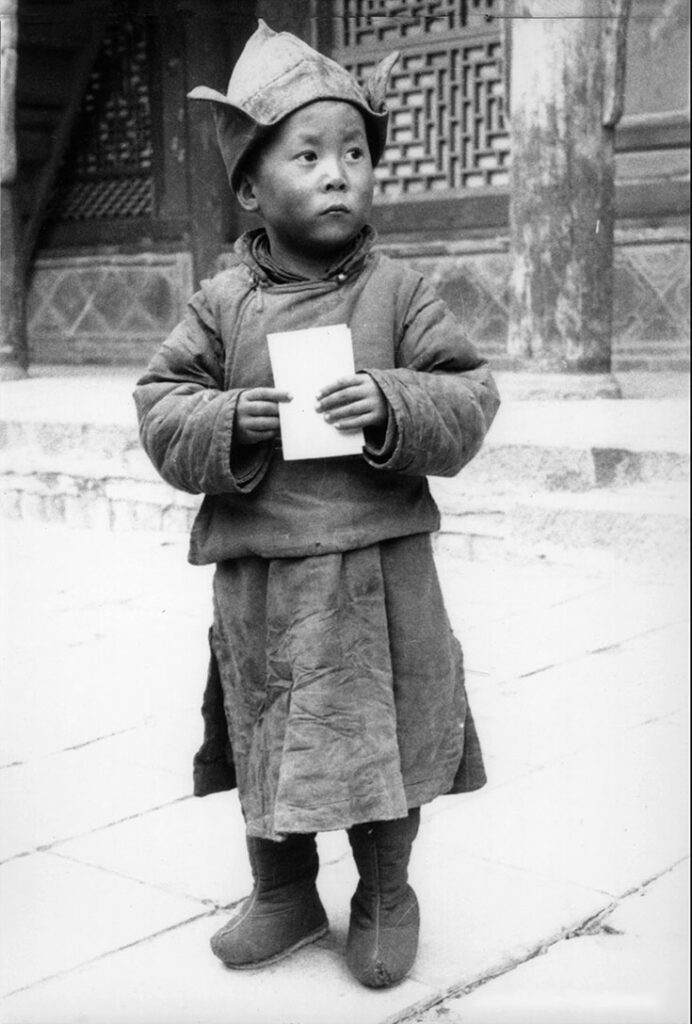

The year was 1937. On a small farm growing barley, buckwheat, and potatoes in a far-flung village of northeastern Tibet, a little boy sat among chickens in a coop, happily clucking along. The boy and his family lived in a farmhouse with a strangely irregular roofline. Life was hard. His mother had given birth to sixteen children, of whom only seven survived.

Beyond this remote plateau—ruled for centuries by a religious monarchy and home to some six thousand monasteries, temples, and shrines—the modern world was entering a period of massive change that would affect the life of that small boy in ways he could never imagine. The Emperor of China had been deposed decades earlier, catapulting China into turmoil. It would soon be invaded a second time by Japan while radical factions readied themselves to exploit the chaos. Farther north, Stalin ruled Russia with designs on expansion. In India, Mahatma Gandhi’s independence movement, which would end the British Empire, gathered steam. In Europe, Adolf Hitler was poised to attack in every direction.

For some months, a search party had been zeroing in on the little farmhouse, having determined from a prophetic vision that the next Dalai Lama would be found in the province of Amdo, near the monastery of Kumbum, living in a house with a peculiar roof. When the party spotted gnarled branches of juniper on the top of the farmhouse, they took it as a sure sign and presented themselves as weary travelers needing to spend the night.

The party’s leader, Kewtsang Rinpoche, passed himself off as a servant, the better to observe the child without creating a fuss. The child, whose name was Lhamo Thondup, correctly identified the Rinpoche’s home monastery.

A few days later the party returned and revealed their intention. Following long custom, they presented the boy with items that had belonged to the previous Dalai Lama, among them a ritual drum and a walking stick. Seeing these possessions, he’s said to have exclaimed, “Mine, mine.” While there were other candidates, these circumstances convinced those in power that this child qualified to be installed as His Holiness, Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama.

The Origins of the Lineage

Monasteries—and the Buddhist schools of thought (lineages) that linked the monasteries into great networks—were the most powerful institutions in Tibet. Like all institutions they faced the problem of succession: How could the spiritual and material inheritance be handed down from one generation to the next intact without being taken over or co-opted by factions, both secular and clerical, seeking power and wealth?

In Tibet, various forms of succession existed, including senior teachers being able to marry so they could pass the lineage on to their children. But for those who chose to remain celibate, this wasn’t an option.

In the twelfth century, the leader of the Kagyu lineage, known as the Karmapa, decided to initiate a system based on the Buddhist belief that an adept practitioner, a bodhisattva, can choose their rebirth and give indications of where their next incarnation can be found. While Buddhists far and wide held the view that the Buddha had purposely reincarnated to help beings and would do so again, no one had ever before applied this principle to other great teachers.

So, the Kagyu lineage was the first to pass leadership through reincarnated beings (tulkus), but the system soon spread widely in Tibet. Though the Gelugpas—the newest, largest, and politically most powerful lineage—were initially reluctant to adopt the system, they soon discovered it could be helpful. The tulku system would ensure the continuation of the line of Gelugpa monks who became the ruling monarchs of Tibet: the Dalai Lamas.

Just to make things a little confusing, the first Dalai Lama wasn’t called the Dalai Lama during his lifetime, nor was the second. The name of the first was Gendun Drup. He lived in the fifteenth century and was a close student of the Gelugpa lineage founder Tsongkhapa. Gendun Drup became abbot of one of the three prominent monasteries Tsongkhapa had established and also founded a new monastery, Tashilungpo.

After Gendun Drup died in 1474, his students recognized a successor, Gendun Gyatso, to inherit his leadership responsibilities and carry his work beyond one lifetime. The pattern was set. Therefore, when Gendun Gyatso died in 1542, his reincarnation, Sonam Gyatso, was recognized the following year, and the saga of the Dalai Lamas began.

While Tibet had many clans and warring chieftains in its history, the nation overall was never dominant militarily and unlike many of its neighbors never sought to vastly expand beyond its natural boundaries. Not so the Mongols. Interestingly, although the Khans were conquerors, they were also attracted to Tibetan spiritual teachings. So, in 1577, Altan Khan sent a large delegation with camels, horses, and provisions to Tibet, beckoning Sonam Gyatso to come to Mongolia.

When Sonam Gyatso visited, the Khan was so impressed that he made a proclamation affirming Mongol patronage of Buddhism and bestowed on Sonam Gyatso the Mongolian title Dalai, meaning “ocean.” The name stuck. The two previous incarnations were posthumously called Dalai Lama, and all future incarnations up to the present day have carried this name.

Temporal Power

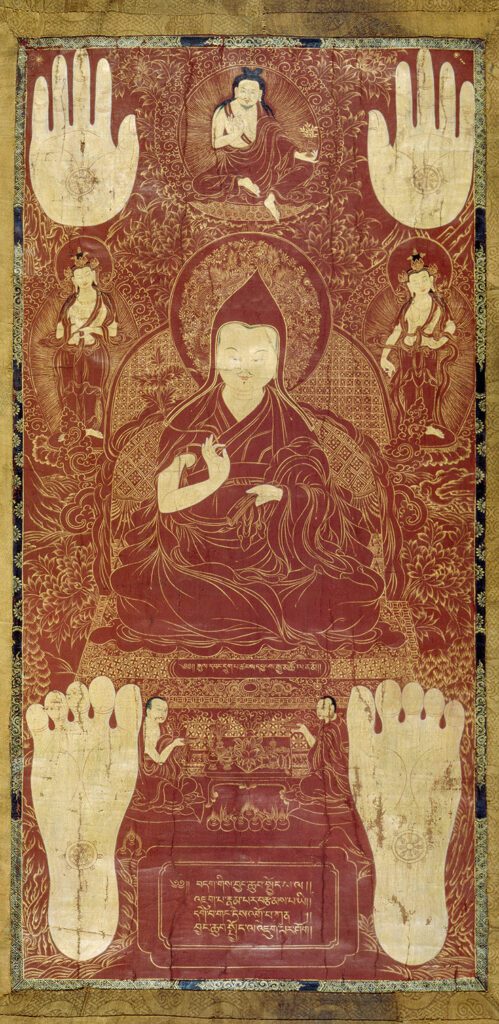

The early Dalai Lamas didn’t hold political authority, but what accounted for their significance, and the ultimate power of the Dalai Lamas altogether, was their strong connection to compassion teachings, especially those of the Kadam tradition.

Thupten Jinpa—Tibetan scholar and principal translator for the Dalai Lama since 1985 who has edited more than ten of his books—explains: “The bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokitesvara, had long been understood as a special deity overseeing the land and people of Tibet as a domain of compassionate action, and the Dalai Lamas came to be recognized as belonging to that broad narrative.” In short, the Dalai Lama was regarded as an emanation of Avalokitesvara with a role to oversee the propagation of the teachings and practices of compassion.

Despite the widespread practice of a religion based on nonviolence, there was tremendous infighting within Tibet. While countless dedicated monastics and wandering yogis practiced Buddhist rituals transmitted from India a thousand years before, not all monastics were engaged in deep study and practice. Some even took up arms. In addition, powerful feudal lords and merchants, who were also patrons of monasteries, had interests to protect and expand. By the time of the discovery of the Fifth Dalai Lama in 1617, the internecine squabbles reached such a level that the boy had to be held in seclusion for fear he might be killed. (The Fourth Dalai Lama, a Mongol, had died at twenty-seven under questionable circumstances.)

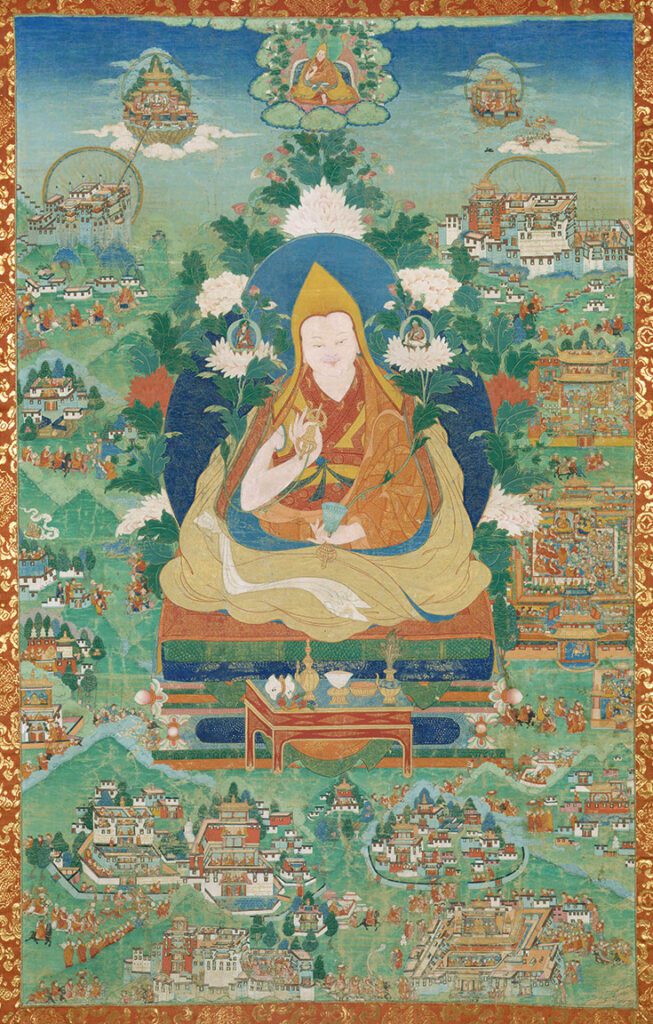

Ultimately, with the help of the Mongols and their troops, the Fifth Dalai Lama was able to quell the infighting among the various factions and establish himself—and the Dalai Lamas after him—as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet, formalized at an enthronement ceremony in 1642 overseen by his patron, Gushri Khan. A few years later, the Fifth expanded an existing building in Lhasa to create what would become the massive, thousand-room, iconic fortress and palace, the Potala.

According to Jan Willis, professor emerita of religion at Wesleyan University, “He’s revered as ‘the Great Fifth’ because he unified the many factions and moved the center of power to Lhasa from the more remote Shigatse, where the first Dalai Lama had been located—essentially proclaiming a new central focus and identity for the nation of Tibet.”

Of the Fifth, Thupten Jinpa says, “Not only did he bring together a splintered group of regions into a single nation unified by language, tradition, culture, and Buddhism, he was also a highly influential spiritual leader: he revolutionized Tibetan painting of religious imagery [thangkas]; was instrumental in encouraging the printing of major texts; and aided the development of Tibetan medicine and astrology. He was not a hard-nosed, puritanical, sectarian Gelugpa, but was more ecumenical with a strong attachment toward the oldest lineage in Tibet, the Nyingma tradition.”

Untimely Deaths

Not all Dalai Lamas are created equal. While the tradition held together from the death of the Fifth in 1642 through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was at times a rocky road and came perilously close to falling apart.

As Thupten Jinpa says, “One of the weak aspects of the reincarnation model of succession is that it requires the predecessor to pass away and a new child to be found, leaving a gap of roughly twenty years during which power has to be wielded by someone on behalf of the teacher. Human beings being human beings, power is addictive and can lead to abuse. The regents who were in place ‘in the meantime’ essentially ruled Tibet and didn’t necessarily give up that power easily.” And when they did turn over authority to the Dalai Lama, they often remained de facto rulers in power-behind-the-throne fashion.

On top of that, Tibetan rulers needed to contend with the power of both the Mongols and the Chinese and the shifting relationships between those two world powers, which always had representatives lurking or even lording over things in Tibet. While the relationship with these “protectors” was understood to be “patron to priest”—with Tibetan teachers supplying the spirituality and the great powers ensuring Tibet’s continued existence—the prospect of invasion always loomed.

The power plays and intrigue began after the Fifth passed away in 1682. The regent concealed his death for fifteen years, claiming he was in retreat, and recognized the Sixth in secret. The Sixth was enthroned as a teenager, and after completing his monastic training at age twenty, he rejected full ordination, took off his robes, and lived as a layman—having relationships with women and drinking alcohol. He famously even wrote beautiful love poems.

The Khan was so enraged at the deceptions of the regent that he allied himself with the Chinese Emperor to have the Sixth deposed, replacing him with his own candidate and effectively taking over rulership of Tibet. Yet the Tibetan people never accepted the replacement. The original Sixth was sent to Beijing to bow before the Emperor (presumably to atone for his lay lifestyle), but he died or disappeared on the way under mysterious circumstances.

After many back-and-forths, a candidate, whom the Sixth had prophesied as he left Lhasa, was installed as the Seventh Dalai Lama. By this time, the Chinese had wrested control from the Mongols, so the lineage came under the protectorship of the Chinese Emperor. This marked the beginning of a new system: the Dalai Lama or his regent would rule, overseeing a council of ministers, but close by there would be Chinese representatives prying and meddling.

While the Seventh and Eighth Dalai Lama both lived to be nearly fifty (a relatively long life for the era), the Ninth died at nine years old, the Tenth at twenty, the Eleventh at seventeen, and the Twelfth at twenty—and quite possibly not by natural causes. Dalai Lama was not an enviable job; it was not good for your health. And needless to say, none exercised political power in the period that covered almost the entire nineteenth century.

The End of Isolation

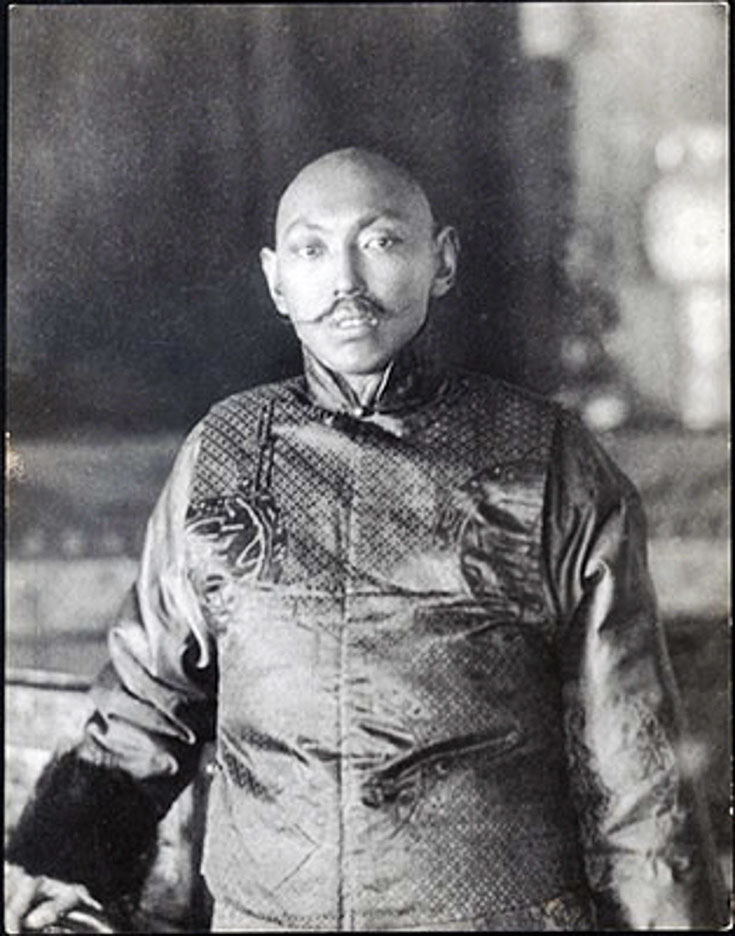

Things changed radically with the Thirteenth, the current Dalai Lama’s immediate predecessor. Facing enormous pressures, he became known as “the Great Thirteenth” because of his valiant efforts to assert and maintain Tibetan autonomy as a nation.

Born in 1876 and recognized two years later as the Dalai Lama, he assumed power in 1895 at age nineteen. While he was getting his feet wet in his role, the British became suspicious that the Tibetans were colluding with the Russians. (They weren’t.) Ostensibly on a trade and diplomatic mission, the British entered Tibet with an armed force.

When the Tibetan army put up resistance, they were mown down, losing over two thousand combatants. The Dalai Lama fled and remained in exile in Mongolia and China for five years, leaving government officials to reach a diplomatic agreement with the British. No sooner was the Dalai Lama back in Lhasa than the Chinese invaded in early 1910, officially deposing him and sending him back into exile, this time in India. The British, now friendly neighbors, reached a pact recognizing Tibetan independence. The rapidly weakening Qing dynasty was unable to carry on in Tibet, opening the door for the Dalai Lama to return in 1913. But Tibet had been badly bruised.

“Tibet’s political leaders were naïve,” Thupten Jinpa says, “thinking that since they had no imperial designs, they’d be left alone. They remained so insular. From his time in India, and through the friendships he made there, the Thirteenth was more exposed to what was happening in the world and came to see just how isolated and lacking in foreign relations Tibet had been, and how vulnerable it would be to many outside forces. It strengthened his resolve to strongly proclaim the sovereignty of the Tibetan nation.”

Toward the end of his life, the Thirteenth’s fear of Communist rule grew to the point where he left, in Thupten Jinpa’s words, “something like a prophecy, that if the Tibetans did not get their act together, the red threat might overtake the nation, the faith, and the people.”

Becoming the Fourteenth

As a Dalai Lama, you don’t get to meet and spend time with your previous incarnation to absorb what they’ve learned. You’re under the tutelage (and biases) of your teachers and in strict monastic training. You learn in time the hand you’ve been dealt.

Shortly after his discovery, the Fourteenth was separated from his family and taken to a monastery, an unhappy period of his life. After eighteen months, he was reunited with his parents and made a three-month journey to Lhasa, marveling at the abundant wild yaks, asses, deer, and geese in the mountains and valleys of the land he was to rule. In 1940, he was formally installed and began an extensive Buddhist education with a strong focus on compassion and wisdom that cuts through illusory beliefs (prajnaparamita). These teachings remain a hallmark of his discourse to this day.

At age fifteen, in November 1950, while still continuing his education, he was officially enthroned as temporal and spiritual leader of six million Tibetan people, who were already under attack by the Chinese on their borders. Shortly thereafter, he dispatched missions to the United States, Great Britain, and Nepal, hoping to persuade those governments to ally with Tibet to secure its independence. None were successful.

His Holiness recalls “feeling great sorrow when I realized that…Tibet must expect to face the entire might of Communist China alone.” A Tibetan delegation that went to Beijing to try to negotiate a withdrawal was forced, at gunpoint, to sign a pact proclaiming the liberation of Tibet by the People’s Republic.

His Holiness himself would spend a year in China starting in mid-1954, meeting with Mao Zedong, Chou Enlai, and others, to no avail. He also spent five months as a guest of the government of India, starting in late 1956. These trips abroad, seeing other nations in action, Thupten Jinpa says, “were formative learning experiences. He returned a changed man, with a much more global perspective.” He saw the contrast between these two massive nations: India a wildly chaotic democracy, China a highly controlled dictatorship.

In early 1959, His Holiness was completing his final monastic exams. Then he was invited by a Chinese general to attend a performance by a Chinese dance troupe without any military escort. Word spread of this obvious ruse and tens of thousands of Tibetans surrounded the Dalai Lama’s residence to protect him from kidnapping.

With the aid of divination, he decided he had to flee. He slipped out disguised as a soldier, made his way through the crowds, and within three weeks crossed the border to India. He was twenty-three years old. Though deeply cherished in Tibet to this day, he’s never been able to return.

New Roles

His Holiness’ picture soon appeared on the cover of Time magazine. He belonged to Tibetans—in Tibet and in the growing diaspora—but now he also belonged to the world. And he faced daunting challenges. As the head of a nation that had lost the land under its feet, he was responsible for nearly one hundred thousand refugees.

Today, His Holiness wears many hats. For those inside Tibet, according to Thupten Jinpa, “His simple presence remains a powerful anchor. The fact that he’s outside in a free country provides consolation, especially when they’re being persecuted, that Tibet as a nation, a people, a culture will endure. For the diaspora, he’s a unifying force for we Tibetans, who are a very tribal people, laying the foundation for long-term continuity. He’s worked hard to establish institutions to foster health, education, and social development. He’s also played a key role in fostering Tibetan Buddhism, including encouraging monasteries with long histories to reestablish themselves.”

It’s tempting when reading blow-by-blow accounts of all the power struggles to overlook the colossal spiritual inheritance preserved in Tibet by the Dalai Lama lineage—a spiritual inheritance that’s now shared with the world.

Venerable Thubten Chodron, founding abbess of Sravasti Abbey, near Spokane, and coauthor with His Holiness of a multivolume series of teachings on the Buddhist path, points to His Holiness’ willingness to try new approaches as one of his greatest qualities. “In 2013, he gave up the role of political leader that had been in place since the Fifth and established a parliamentary-style system, because he felt there were defects in the system he inherited, especially in the modern context. He’s learned a lot about other forms of government and feels that rule by one person is unstable and doesn’t serve the Tibetan people well.”

Thubten Chodron also points out that the distinction he’s developed between Tibetan independence and autonomy represents a realism born of what he’s learned as a world citizen. “He’s thought it wiser,” she says, “to call for the autonomy of Tibet, whereby Tibet would remain within China for international affairs but have control over their own internal affairs and the Tibetan community.” It’s also vital, she says, that he advocates for all the Tibetan lineages, and “helps spread a nonsectarian spirit of buddhadharma and what he calls ‘secular ethics’ throughout the world.”

His Holiness has also been a mover and shaker in encouraging dialogue between Buddhists and scientists, especially those who are studying brain and mind. Adam Engle, who cofounded the Mind and Life Institute, which held thirty-three dialogues with the Dalai Lama and leading researchers, says His Holiness’ involvement and support of the institute, “which created the scientific field of contemplative research, is one of his great lasting legacies. It enabled the careers of many neuroscientists and clinical scientists focused on that research and applications. As a result, the public perception of the value of contemplative practice has shifted from an esoteric spiritual practice for a few to a mainstream mental fitness practice for everyone.”

For Jan Willis, His Holiness stands out as a champion for a peace that includes all of nature. He has called, she notes, “for Tibet to become a zone of peace, a buffer between all these Asian powers, and a place where the earth is respected.” His Holiness has pointed out that the headwaters of many massive rivers lie on the Tibetan plateau, so like the rain forest, it’s a vital part of Earth’s inheritance. “His longtime respect and love for the earth,” Willis says, “was part of the reason he earned the Nobel Peace Prize.

“The Fifth was called ‘great’ for his unifying work. The Thirteenth was ‘great’ for defending Tibet’s independence. The Fourteenth will be called ‘great’ because of what he has given to the entire world.”

What’s Next?

Buddhism is nothing if not realistic about death. His Holiness has been privileged with unprecedented longevity, but everyone knows his life will eventually come to an end. Hence, questions about the continuity of the Dalai Lama lineage have been swirling for decades. Although he’s taken the step of removing the pressure of formal political leadership from the office of the Dalai Lama, he’s still regarded as the overall leader of the Tibetan people, and this worries the Chinese, so much so that in a 2021 white paper on Tibet they reiterated the position expressed in their “Management Measures for the Reincarnation of Living Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism”: all important reincarnations must be approved by the People’s Republic.

According to Robert Barnett, former director of the Modern Tibetan Studies Program, we could very likely end up with two Dalai Lamas: “One selected on the basis of instructions left behind by His Holiness…and one chosen by the Chinese Communist party.”

The Tibetan Parliament in Exile, India, the United States, and other allies have forcefully stated that His Holiness is the sole decision-maker concerning the future Dalai Lama. He himself has been coy, at times hinting he may be the last (perhaps to protect the role from being co-opted by China), yet also saying that he will live to 113 but leave instructions for finding his reincarnation starting after his ninetieth birthday. The uncertainty is no accident. It seems to suit him to keep the world guessing. When pressed, he refers to himself as “just a simple monk.”

Meanwhile, others are anxious. Sonam Tsering, General Secretary of the Tibetan Youth Congress, which has been critical of the Dalai Lama’s call for autonomy instead of independence, nevertheless reveres the Dalai Lama and believes it’s important for him to take rebirth. Last summer, he told Le Monde, “I’m sure His Holiness will be reincarnated.”

For now, His Holiness is very much alive, and ever more widely admired.

Jan Willis concludes with the story of her visit to the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm “Everyone who’s ever received a Nobel Prize is asked to contribute something to the display,” she says. “I spotted the Dalai Lama’s. It was a Tibetan text. I looked closely and saw that it was The Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life by Shantideva, the ultimate teaching on practicing compassion. A pair of rimless glasses lay atop an open page. It was so sweet. Above all, he is a simple monk.”