During my recent pilgrimage to Kathmandu, Nepal, I spent most of my time in Boudhanath, a small town encircling the renowned Boudhanath Stupa—one of the most iconic stupas in the world. This town serves as a vibrant hub for Buddhist art, with thangka painting being one of its most celebrated art forms. Originating in Tibet in the 7th century, thangka painting draws inspiration from Indian traditions and has evolved into a unique Tibetan expression.

I had the privilege of talking with Raju Yonjon from Enlightenment Thangka, whose team has dedicated over two decades to preserving and promoting this sacred art form. Their commitment ensures that practitioners worldwide have access to authentic tools for meditation and spiritual practice. During my visit to their painting studios and galleries, I sat down with Raju to delve deeper into the intricacies of thangka painting and its significance in contemporary Buddhist practice.

Can you tell us about the origins of thangka painting? Where and when did it begin?

Thangka painting is believed to have originated in Tibet around the 7th century CE during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo, who played a central role in introducing Buddhism to Tibet. Over the centuries, different regional styles emerged, such as Karma Gadri, Menri, New Menri, Tsangri, and Mendri. The Karma Gadri tradition, in particular, is known for its landscape backgrounds and spacious compositions, and Menri and New Menri, which are more detailed and symmetrical. In Nepal, the tradition saw a revival when Tibetan lamas and Tibetan artists in exile brought their expertise. Nepali artists, already skilled in their craft, adapted these teachings, leading to a fusion of styles that enriched the thangka painting tradition in the Himalayan region.

“The Tibetan Buddhist art form of thangka painting is a visual and symbolic representation of the spiritual deities, which are utilized on the path to enlightenment.”

What are the primary spiritual or religious purposes of thangkas in Buddhist practice?

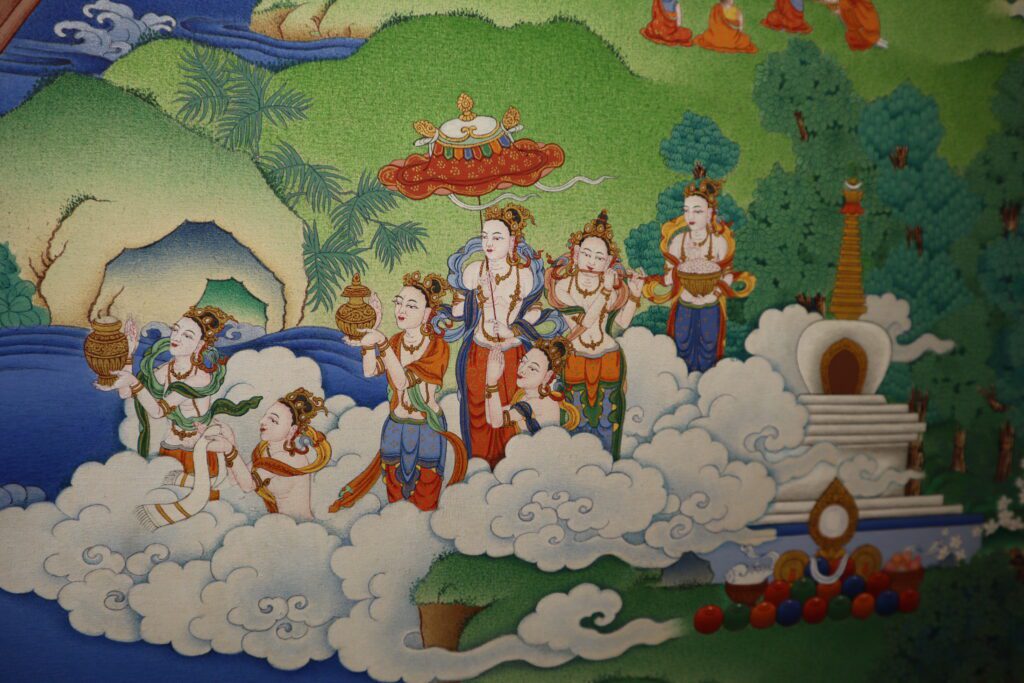

Thangkas are often placed on altars and used as focal points for offerings, prostrations, and recitations. Thangkas serve as a meditation and visualization tool for Vajrayana practitioners. Thangkas act as visual scriptures, conveying layers of philosophical meaning, morality, and cosmology. This was especially relevant in historical contexts where many could not read.

What are the typical materials used in thangka painting?

Traditional thangka paintings are created using many natural materials. The canvas is typically made from fine cotton or silk, stretched tightly on a wooden frame. The surface is then coated with a mixture of animal glue and white clay to create a smooth, absorbent base. The paint used is made of natural minerals like lapis lazuli (deep blue), malachite (green), cinnabar (red), and orpiment (yellow). These stones are sourced from Tibet, ground into fine powders, and mixed with water and glue to create vibrant paints. The use of 24-karat gold leaf is used every day to highlight sacred elements such as crowns, jewelry, and halos. In modern times, it is common to find acrylic paints used for thangka painting.

Natural gemstones, gold, and other minerals are used to make the natural pigments for thangka painting.

Could you walk us through the step-by-step process of creating a traditional thangka?

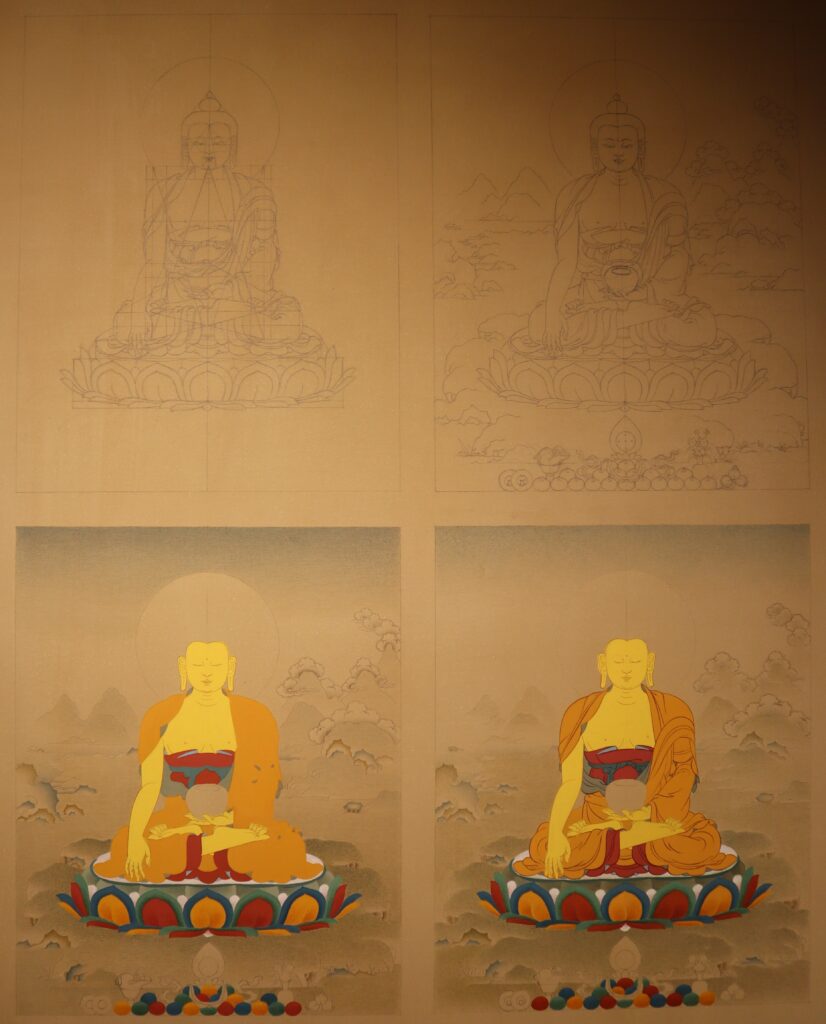

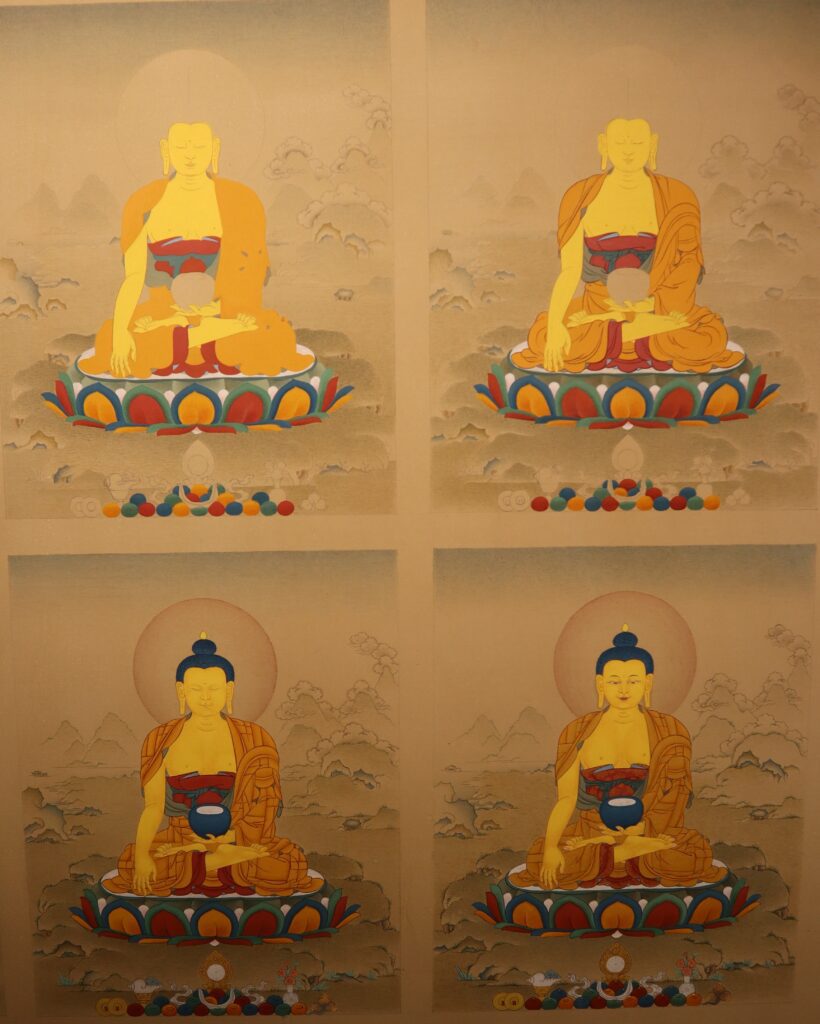

The process of creating a traditional thangka involves several steps. First, the canvas is prepared by stretching cotton or silk cloth tightly on a wooden frame. The surface is coated with a mixture of animal glue and white clay, then polished to a smooth finish. Next, a pencil draft is created using a geometrical grid based on sacred proportions of the deity. The central figure is sketched first, followed by surrounding elements like attendant figures, offerings, thrones, landscapes, and aureoles. Painting begins with background colors, followed by flat layers and shading. Details such as facial expressions, ornaments, and robes are added meticulously using fine brushes. Finally, the eyes are painted last in a ritual called “opening the eyes.” Once the primary colors are in place, outlines are drawn using darker shades. As mentioned, the paint used is made of natural minerals like lapis lazuli (deep blue), malachite (green), cinnabar (red), orpiment (yellow), and 24K gold. These stones are sourced from Tibet, ground into fine powders, and mixed with water and glue to create vibrant paints.

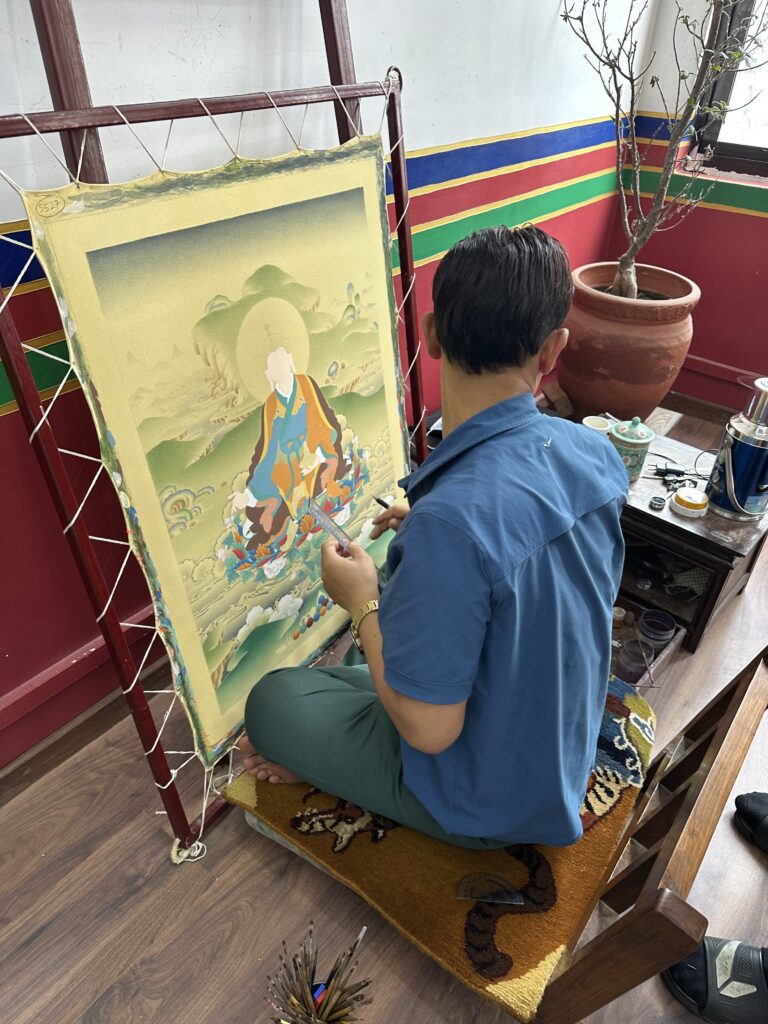

In the traditional thangka painting process, a team of artists collaborates to create each piece. Typically, two to three artists work together on a single thangka, though a master artist can complete one alone. However, this is not commercially feasible due to the high costs involved. Therefore, apprentices, students, and assistants assist in various stages of the painting. The master artist is responsible for the design, composition, body proportions, and geometry of the layout. Apprentices handle the background, landscapes, and other details, while the master artist finalizes the work by painting the faces of the deities. This collaborative approach reflects the traditional Tibetan method, ensuring that large-scale projects, such as mural paintings in monasteries, are achievable.

The stages of progression of a thangka painting.

How long does it usually take to complete a thangka?

The time required to complete a thangka varies depending on its size and complexity. It can take anywhere from one to two months, and it may extend to several years for larger or more intricate pieces.

What training is required to become a thangka painter?

Becoming a thangka painter requires years of disciplined training, often under the close guidance of a master. It is not only about developing artistic skills but also about cultivating spiritual understanding. Training involves mastery of iconography and proportions, understanding the sacred geometry and proportions of deities, learning to mix and apply natural pigments and gold leaf, and gaining knowledge of the symbolic meanings behind various elements.

We have been fortunate to study under the guidance of the Venerable Master Jamyang Phuntsok, a specialist in the Karma Gadri tradition of Tibetan thangka painting. His lineage traces back to the esteemed Karma Gadri artist Thanglha Tsewang of Palpung Monastery in Kham, Eastern Tibet. This lineage emphasizes a distinctive style that integrates Indian proportions, Chinese color techniques, and Tibetan composition, known as the “camp style” or Karma Gadri.

Our master teacher resided in Boudhanath for 15 years, training the master artists we have now, before returning to Lhasa. We continue to consult with him; he recently visited to review our work and make adjustments, and he reminded us that this is dharma work, not merely for profit.

Following his guidance, our master artist trains our apprentices. Apprentices begin by learning the colors and techniques for creating gradients, basic background coloring, shading, and grading. They then progress to adding ornaments to the deity, such as the lining of the lotus and the designs in the deity’s robes. Finally, they learn to draw the deity, focusing on iconography and geometry.

Thangka painting studio.

How do artists ensure that the representations are accurate?

Our Artists ensure accuracy in thangka painting through a structured process that blends traditional guidelines, spiritual mentorship, and hands-on training. This practice has been passed down through generations, emphasizing lineage and adherence to established standards. The process begins with apprentices learning to mix and apply natural pigments, focusing on creating gradients and shading techniques. They then progress to adding ornamental details, such as the lining of lotuses and designs on deities’ robes. Subsequently, they study the iconography and geometry of deities, learning to draw them accurately. Throughout this journey, they are guided by a master artist who oversees their work, ensuring it aligns with traditional standards and spiritual intentions. This methodical approach ensures that each thangka painting is not only artistically precise but also spiritually meaningful, reflecting the deep-rooted traditions of Tibetan Buddhist art.

How are measurements and proportions (e.g., iconometry) determined for deities in thangkas?

In traditional thangka painting, the measurements and proportions of deities are determined using strict geometric guidelines rooted in Buddhist texts. These are found in specific practice texts that practitioners use for their daily practices as well. In this way, the thangka painting serves as a visualization tool for the deity the practitioner is focusing on. These provide guidance on, for example, the number of heads and arms of a deity, the implements and symbolic items, the color and posture of the deity, and the surrounding retinue and mandalas

What role does symbolism play in thangka painting?

Symbolism plays a crucial role in thangka painting. They convey complex teachings on impermanence, emptiness, karma, and liberation through symbols. Each element of a thangka painting is rich in symbolism, and each symbol has meaning, aiding the practitioner in their practice.

Can you explain the meaning of some common figures or symbols found in thangkas?

In Tibetan thangka painting, various symbols are employed to convey profound spiritual meanings. The lotus flower represents purity and spiritual awakening, emerging untainted from the “mud” of samsara. The vajra, symbolizing unbreakable truth and power, embodies the male principle of method. The bell (ghanta) signifies wisdom and emptiness, representing the female principle. The conch shell serves as a proclamation of the Dharma, awakening beings from ignorance. The flaming sword symbolizes wisdom cutting through delusion and ignorance. The skull cup (kapala) signifies the transformation of negative forces into wisdom nectar. Lastly, the deer embodies peace and gentleness and also symbolizes the Buddha’s first teaching at Deer Park.

How is the tradition of thangka painting being preserved today? Are there challenges to maintaining traditional techniques in the modern world?

Machine-printed thangkas and inexpensive factory-made items have flooded the market, often at a fraction of the cost of traditional, hand-painted works.

Fewer young people are committing to the decade-long training needed to become master painters. Not many young people are interested in this tradition; they want to find other jobs or work in fashion, and many young Nepalis are leaving the country. We are really trying to train and pass on knowledge to young people, encouraging them that this can be a good career path.

We are also trying to promote individual artists. We want to give credit to the artists when they paint a thangka, something that traditionally has not been done. Thangkas are often anonymous, and artists are not recognized. This is a valuable art form, and we want to preserve this traditional practice. We want to promote artists, use the best resources to bring out the finest thangka. Authentic materials are expensive and harder to source, and modern synthetic alternatives, though cheaper, compromise the spiritual and visual integrity of the art.

We are Buddhist practitioners. We have respect for the art and the tradition. These are sacred images. From a spiritual point of view, we are invested in this to preserve the art, promote practice, and consult with Khenpos and Lamas to ensure we have the correct iconography and details. We want our images to be correct so that they can be authentic tools for practice, not just decoration. We have a deep appreciation for this art form, and we want to present it in the best way we can.

The photos featured in this article were taken at the Enlightenment Thangka studio and gallery with their permission. To learn more or to explore Karma Gadri thangka art, visit www.enlightenmentthangka.com.