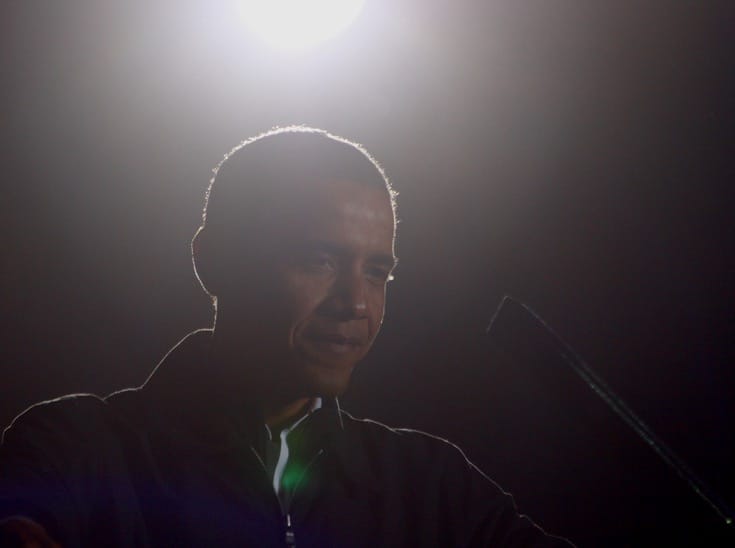

There are many things we can say about the historically unprecedented campaign of Senator Barack Obama to become America’s first non-white president, but one thing we can certainly expect the general election in November to do is take the temperature of racial attitudes in America at the dawn of a new century.

For Buddhists, awakening is the goal of our practice. After decades of meditation, daily spiritual practice, and study of the dharma, we find ourselves acutely aware of how intellectual constructs can create illusion or ignorance (avidya), and fuel divisiveness and dualism in our lives. Clearly, one of the most toxic of these illusions is the notion of “race.” To be sure, it is a political issue. But more importantly, it is an enlightenment issue as well.

By now we know—or should know—that race is our grandest lived delusion and grief-causing fiction: “a social construction,” says Stanford University historian Richard White, who reminds us that at one time the Irish, Jews, Poles, and southern Europeans were excluded from the exclusive social club of “whiteness.” As scientists continue sequencing the genome, they find no biological basis for race. Sharon Begley’s 2003 “Science Journal” column in The Wall Street Journal reported that, “Geneticists find that when they add up the tiny genetic variations that make one person different from the next, there are more differences within races than between races.”

Obama is, as he himself has said, a kind of blank slate onto which Americans have projected their deepest and most visceral social and cultural longings.

“Race has no basic biological reality,” Jonathan Marks, a Yale University biologist, reported in a Knight-Ridder newspaper article. “The human species simply doesn’t come packaged that way.” Stanford geneticist Luigi Cavalli-Sforza added, “The characteristics that we see with the naked eye that help us distinguish individuals from different continents are, in reality, skin-deep. Whenever we look under the veneer we find that the differences that seem so conspicuous to us are really trivial.”

Yet, for all that, we continue to live the lie of race, which according to an article in a 2003 issue of Science News literally makes us stupider. “White people who hold biased feelings toward blacks have to work to control their thoughts and behaviors during interracial encounters,” said Dartmouth psychologist Jennifer Richeson. “This social strategy depletes the limited pool of mental resources available for monitoring and using various types of information.”

Even before the current popular interest in DNA research, Guy Murchie wrote in The Seven Mysteries of Life that if we trace our ancestry back fifty generations to C.E. 700, we find we all share a common ancestor. None of us, Murchie insists, can be less closely related than fiftieth cousins. “Your own ancestors,” he wrote, “whoever you are, include not only some blacks, some Chinese, and some Arabs, but all the blacks, Chinese, Arabs, Malays, Latins, Eskimos, and every other possible ancestor who lived on Earth around A.D. 700 … It is virtually certain therefore that you are a direct descendent of Muhammad and every fertile predecessor of his, including … Confucius, Abraham, Buddha, Caesar, Ishmael, and Judas Iscariot.”

Murchie’s observation is, for those with dharma-trained eyes, a statement of dependent origination (pratitya samutpada), or what Thich Nhat Hahn calls our “inter-being.” My point, if it isn’t clear yet, is that race is maya, a chimera constructed for reasons of social, political, and economic domination, and for the comfort of fragile, insecure egos.

It is easy to recognize in the biography of Barack Obama this interpenetration of backgrounds that transcends dualism. There is the white mother from that most iconic of states in pop culture (Kansas, for heaven’s sake, Toto), the Muslim father from Kenya (which makes him genuinely African-American), his formative years spent in Indonesia and his Indonesian half-sister, and Hawaii (a state of considerable multicultural diversity). Indeed, his clearly multiracial background, like that of Tiger Woods, Halle Berry, and, if we scratch ourselves deeply enough, all of us, indicates a demographic that will only vividly increase in the twenty-first century, with the generic and misleading terms “white” and “black” consigned to the dustbin of human history.

Obama’s approach has not been the disjunctive, polarizing “either/or” style of the past eight years, but instead is conjunctive, in the spirit of “both/and,” which is far more compatible with the dharma.

In fact, it is primarily this subtext—his cosmopolitan, globe-spanning background and sensitivity—that made the initial public response to Obama after the Iowa primary nothing short of primal, and he and his wife Michelle the stuff that dreams are made of, symbols for a new century and its desire to transcend tribalism and the barriers between people. With little political history or baggage to weigh him down (which to his opponents is an Achilles heel), Obama is, as he himself has said, a kind of blank slate onto which Americans have projected their deepest and most visceral social and cultural longings.

For black people, the promise of his becoming president is the “impossible dream” their ancestors had nurtured since the era of slavery. For whites, a presidential candidate of color—especially one who in his speeches transcends decades of Balkanization along the lines of race, class, and gender—means that the ideals of equality and opportunity enshrined in the nation’s most sacred documents are not just fine-sounding words but a tangible possibility that might take place in our lifetime. And across the planet (in a Muslim nation, a man told reporters the freshman senator looked like people he saw every day), Obama’s seemingly exotic but in fact very common background is inspirational because, as he told an audience of 200,000 in Germany, he is an American who views himself as “a fellow citizen of the world.” At a time when the prestige of the United States has been badly damaged abroad, Obama’s approach has not been the disjunctive, polarizing “either/or” style of the past eight years, but instead is conjunctive, in the spirit of “both/and,” which is far more compatible with the dharma.

Predictably, Obama’s universality has triggered both confusion and criticism. As David Brooks said in The New York Times, “There is a sense that because of his unique background and temperament, Obama lives apart. He put one foot in the institutions he rose through on his journey but never fully engaged … This ability to stand apart accounts for his fantastic powers of observation, and his skills as a writer and thinker. It means that people on almost all sides of an issue can see parts of themselves reflected in Obama’s eyes. But it does make him hard to place.”

Eloquent and elegant, charismatic and holding a degree from Harvard Law, always comfortable in his skin, he and Michelle are also avatars of a new black America of the post-civil rights period: namely, of two generations of high-achieving, disciplined black professionals—historically transitional generations—whose accomplishments are everywhere evident in fields as diverse as business, the sciences, education, law, and the entertainment industry. Has the hour arrived, then, for a member of this generation to move into the White House?

Perhaps it would be best to describe the Obama phenomenon as being, from a Buddhist perspective, not so much revolutionary as potentially evolutionary. But if so, then one problem Obama faces are people who do not want to evolve beyond the ancient stupidity and error of epidermalizing the world, who are attached to the idea of a racial (or geographic) identity as a way of avoiding the experience of their true nature as interconnectedness or emptiness. Or, if you prefer existentialist thought to the buddhadharma, see this in terms of Sartre’s famous statement, “Existence precedes essence.”

In other words, the meaning of our lives is never pre-given: whatever meaning we find is based on our deeds, actions, and, as Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “the content of our character.” The senator from Illinois, who repeatedly rejects obsolete ways of thinking and talking about race, predictably finds himself walking a cultural tightrope, always performing with balance, remarkable grace, and civility when attacked by those with a tribal mentality (white, black, and otherwise) who feel most threatened by the monumental sea change his presence in American politics represents. If his campaign fails, it may well be for the reason Charles M. Blow identified in an op-ed piece in The New York Times: the inability of American voters to “let go” the illusion of race. If he wins, we may have the possibility of a bit of liberation and relief from centuries of racial masks and dissembling.

For Obama understands that a black presidential hopeful can only become the leader of the most powerful nation in human history if he rises above the racially provincial and parochial; if his humanity, empathy, and compassion are strongly felt to be genuine by his “fellow citizens of the world.” That is one enduring lesson of this dramatic, unprecedented campaign. And whether he wins or not in November, the truth that excellence is color-blind, and that broad service to others has no tribal affiliation, will live on in our memories long after the general election is over.