“I solemnly swear that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich . . . that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, that I will faithfully and impartially discharge all duties incumbent upon me.” —from the Judicial Oath of the United States 28 U.S.C. § 453

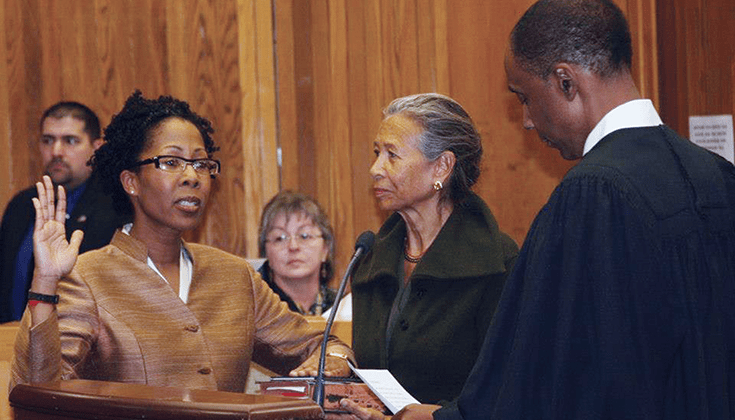

Two oaths serve as the foundation for my daily practice: my Judicial Oath of Office and my oath to follow a spiritual path of awakening for the liberation of all beings. I serve as a magistrate judge within the District of Columbia’s trial court. I also practice Buddhism, training in the Theravada tradition under my primary teacher, Gina Sharpe.

Judging gets a bad rap. To many, a judging mind is to be avoided. Back when I used to teach mindfulness as “paying attention to everything that arises without judgment,” someone asked, “Can you be mindful and be racist?” My answer: Only if mindfulness is uprooted from its moral underpinnings.

The Buddha spoke of how he came to his own judgments in upholding the monastic codes. The Dhammatthavagga Sutta advises wise judges to unhurriedly and impartially weigh both right and wrong judgments before making a decision according to an intelligence in line with the dharma, guarding the dharma, and guarded by the dharma.

I have never had a better understanding of the First Noble Truth than when I began sitting on the bench and witnessing as the 10,000 joys and sorrows arise and fall within all walks of life.

Drawing from these teachings, I now understand mindfulness as intentional awareness. The practice of mindfulness involves weighing our alignment and realignment with our truest intentions. For me, these intentions may be the eightfold path, commitments to loved ones, the Judicial Code of Conduct, or my Oath of Office.

Much of my understanding of the first noble truth has come from sitting on the bench and witnessing the 10,000 joys and sorrows arise and fall within all walks of life. Our communities, homes, and institutions are plagued with addiction, unemployment, violence, and abuse. Often, our misguided and clumsy attempts to secure our own physical or financial safety and guard against pain only cause more suffering. At the epicenter is the courthouse, where communities seek to “make things right.”

Trial judges, by necessity, develop thick skin because one half of all parties before us believe our decisions are wrong. Sometimes the only way to know the law has been applied fairly is when all parties are equally unhappy.

Upholding the values shared by both my code of conduct and my practice while presiding over a high-volume court docket requires skillful effort—and some reliable tools. Indeed, if Martin Luther King, Jr. is right, and “Justice is power correcting everything that stands against love,” then every judge needs to acquire a set of personalized power tools.

A daily sitting practice, dedicated dharma study, and a network of spiritual friends are all part of my personal tool belt. Community volunteerism, in particular, allows me to remain mindful of a vision of justice that’s broader than what’s defined by laws. My engagement with a local restorative justice dialogue forum called Justice in Balance allows me to support the empowerment and reconciliation of community members impacted by the forms of violence not typically prosecuted in court.

My responsibilities on the bench are a constant resource for the tangible application of and support for mindfulness. Mental restraint and discipline are tools I rely upon much more often than external threats or commands. Instead of using a gavel, my training as a judge has taught me to use respectful words and disciplined listening to communicate legitimate authority. For, as the Five Remembrances says, My actions are my only belongings. I cannot escape the consequences of my actions. If I cannot remember this simple rule of karma, I can at least recall that every statement I make in court is contemporaneously recorded, often transcribed, and periodically appealed.

One of my spiritual mentors, Bhante Buddharikkita, enjoyed laughing at the shared formalities within our chosen livelihoods—starting with the love/hate relationships with our robes. I understand how the black robe might intimidate and create distance, increasing perception of my size and power. But it also serves to remove some of my self from the equation. Just as we can’t pick out only the laws that suit us personally, we can’t pick a robe color meant to flatter us.

Through my spiritual practice, I have discovered that the judicial uniform can be used to cultivate connection: my robe is another mindfulness tool, holding me accountable to my oath of office as well as to my dharma practice off the cushion.

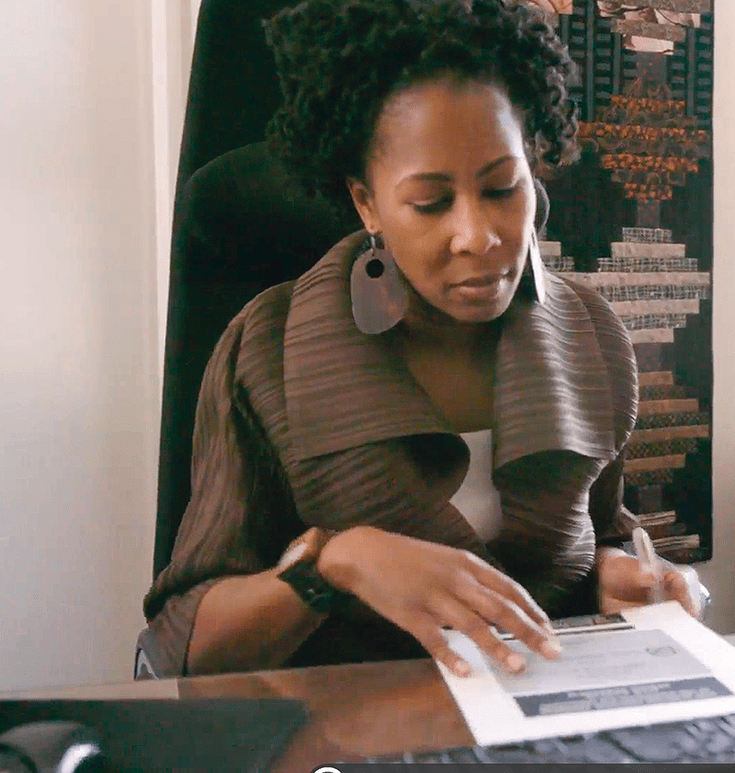

Immediately before I take the bench each morning, even when I’m rushing, I commit to a brief “robing meditation,” which returns my attention to internally cultivating nonself and externally communicating collective strength. I ground myself in the humbling impact of being cloaked in a symbol of the justice I am charged with administering. I take stock of present bodily sensations and thought formations and examine which of them may interfere with my faithful and impartial discharge of duties. Guided by my court training and the Vitakkasanthana Sutta, I then endeavor to either set distractions aside, relax their grip on my mind, or if all else fails, crush my egocentric mind with clenched teeth and open awareness.

Finally, the robe is a great reminder that I am responsible for the laws I’ve vowed to uphold—even when it’s uncomfortable or the laws are not equitably drafted or equally enforced. Ten to fifteen thousand members of the public enter my courthouse each day, and most are suffering. None, except possibly the newlyweds, want to be there. People are distressed by the circumstances that brought them to court, and many are looking for someone to blame.

I have witnessed in my courtroom the transformative impact of training the mind to drive all blame toward self.

A lot of that blame, justifiable or unjustifiably, is directed toward the bench, and very little of it is expressed through wise speech. Chögyam Trungpa, in his commentary on Atisha’s eleventh-century mind-training teachings, claimed that “everybody is looking for someone to blame—and they would like to blame you . . . because they probably think you have a soft spot in your heart.” I have witnessed in my courtroom the transformative impact of training the mind to drive all blame toward self. Defensiveness inevitably feeds newly tapped rage. I surrender my verbal weaponry in order to defend due process from counterattacks. When I am the first to concede or affirm the harm of someone before me, I’ve found that litigants listen more easily and treat each other more respectfully. Sometimes the energy shifts away from seeking retribution and toward problem solving when I absorb unfair accusations. (Sometimes, nothing at all happens.) An entire field of research is now dedicated to this simple truth: if people have a voice and are treated with respect, they typically perceive the proceedings as fair and the system as just, regardless of the outcome of their case. Ironically, if I accept that sometimes the law “gets it wrong,” people are more likely to believe the law got it right.

Like some monks and nuns, we trial judges are challenged to distance ourselves from and limit certain social and personal interactions—without succumbing to a sense of isolation. We are challenged to deliver instruction in a vernacular relevant and accessible to all without overstepping the training rules formulated for us. We are tasked to apply the Buddha’s teachings in wise speech and skillful means in highly visible settings. We are challenged to uphold, privately, the same vows we’ve taken publicly. To do otherwise would undermine the integrity of the law itself.

As I enter the courthouse, I am excited to meet each day’s challenges. Sometimes I transcend them. Sometimes I feel beaten down by them—until I remember to bring appreciative attention to the never-ending freedom to practice with the pain and difficulty before me.

When I remove my robe at the end of the day, having stood witness to so much conflict and trauma, my heart is softened. I must remember that I always have the choice to close my ears or my heart. But as MLK put it, I choose love.

Though I am privy to only a sliver of each litigant’s life, I am struck by how often I hear my sorrow in their voice, surprised by how often I see my own weariness in their eyes. In those brief moments, I get a small taste of the transformative power of King’s vision of justice.

Then I bow to Kwan Yin and to King. And start again tomorrow.