As practitioners, it’s important to make the distinction between the kind of silence that liberates and the silence that imprisons. Silence has the potential for lasting transformation, but it can too easily be weaponized in service of greed, aversion, and delusion. That’s why it is so important to understand the difference between noble silence and its shadow, ignoble silence.

What Makes Silence Noble?

Almost all Buddhist traditions maintain some practice of noble silence, to varying degrees. That’s not surprising considering the Buddha in the earliest texts speaks often in praise of silence.

For example, there’s the near-total quiet of a Vipassana meditation retreat, usually sustained for short but intensive periods of time. There’s also the integrated noble silence of mealtime gatherings in the Plum Village tradition—twenty to thirty minutes of quiet eating before conversation (or getting up for seconds).

The use of silence in these scenarios has a purpose. It’s to create the right conditions to be with ourselves and examine our internal world. We take some time just to observe this body, this mind, this heart. What’s going on there? What’s happening in this conglomeration we call our “self”?

When we’re engaged in activities, whether it’s work or socializing, that require both our attention and our speech, it’s difficult to wholeheartedly observe what’s occurring in our physical and mental experience. Of course, it’s not that there’s anything wrong with doing these activities. But we need to make time in our lives for both speech and silence.

It’s essential that from time to time we find a moment to batten down the hatches and look closely at what’s going on within our body and mind. When there’s awareness, there’s the possibility of growth, change, and transformation. Silence helps us cultivate this awareness, whether it’s the collective silence of a Buddhist retreat or the solitary silence of our daily meditation practice.

Just twenty or thirty minutes in the morning or evening to meditate silently can be a form of going on retreat. What do you retreat from? Temporarily, the world out there. You retreat from the sights, sounds, scents, flavors, sensations, and even thoughts of the world. These normally occupy our attention throughout the day; in meditation, we stop and look deeply, as the venerable Thich Nhat Hanh would say. We look at what’s alive for us at this moment.

Sometimes we’re surprised by what we see. It’s not that something hasn’t been there for some time. But we just couldn’t see it. Out of nowhere, a deep-seated anger bubbles up, or that years-old grudge. We may think meditation should be peaceful and calm and suddenly—boom!— we’re agitated and upset.

It’s like trying to peer into a pond that’s been churned up by a storm. It’s murky. All those raindrops distort the surface of the water. But when the downpour subsides and everything become calm, our mind, like the pond, becomes clearer. The things we see below the surface may not be what we wish to see. But if we can face them, we can do something about them.

Cultivating this silence—of speech and of the senses generally—allows us to stop and see more clearly. This is what makes silence wholesome, makes it noble, makes a foundation for wisdom and compassion.

With noble silence, you start where you are. Initially it may be uncomfortable, finally being in solitude with your own being. But you can allow that discomfort to teach you how to become reacquainted with yourself. Hello there, good to see you again!

These small moments then lead to bigger moments of deep concentration and peace that meditation allows us to access. Letting the mind be still, letting the mind be quiet—that’s really all it takes.

It’s important to recognize that noble silence should feel nourishing. Not necessarily comfortable, but beneficial. We’re not trying to cultivate an aversive silence. If there’s pain, it should be the pain of release, not the pain of repression, which has a totally different tone.

We’re also not trying to cultivate the state of mind that gets angry at every little sound around us. We don’t live our lives in sensory deprivation chambers, and we can’t bend every condition to our liking. That brings us to how something so noble can devolve.

Ignoble Silence: The Other Side of the Coin

The “evil twin” of noble silence is ignoble silence. This is the kind of silence that springs from unwholesome states of mind and leads to suffering. It is not something the Buddha praised. It is the silence of fear, of violence, and of shame.

Take a moment to consider what this might look like in your own experience, or that of people you know, or in the larger culture. What kind of silences do we impose on others or ourselves out of a fear of speaking?

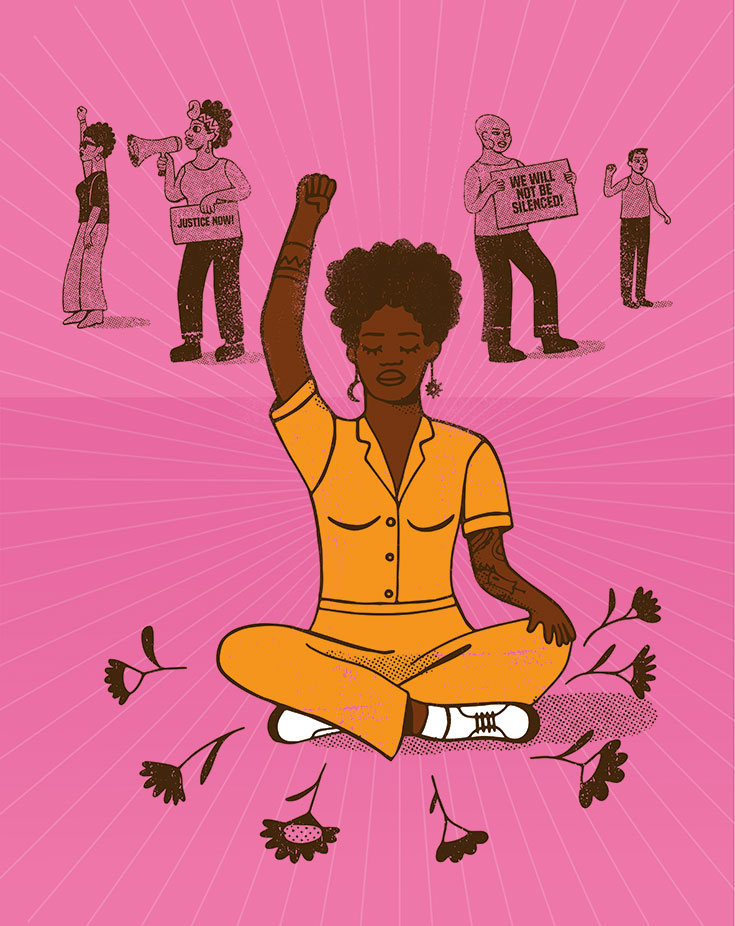

I think of the myriad ways women, queer people, and folks of color (along with other historically marginalized groups) have been othered and silenced by the dominant culture. When we speak, we’re told to shut up. That kind of silence is the silence of oppression.

This is especially a problem when what we could say aligns with truth and justice, wisdom and compassion. When speaking could have so much benefit. This is especially important to contemplate for those who have the power and privilege in society to speak out, but don’t.

In one early discourse, the Buddha speaks in disappointment of someone who doesn’t criticize a person worthy of criticism, or who doesn’t praise that which is worthy of praise. We see, then, that ignoble silence is related to practicing the noble eightfold path in a distorted way—with wrong intention, wrong speech, and wrong action.

When we encounter someone suffering, we don’t just ignore them. We don’t throw our hands up and say, “Well, it’s all I can do to take care of myself.” We help if we can. Sometimes that help is in the form of a kind word. Or in standing up for what is right and true—in a letter, in a speech, in a conversation. We don’t stay silent in situations where speech is called for. Instead, we follow the Buddha’s instructions on virtuous speech: speaking words worth treasuring, words that are helpful and true. Words of benefit. Then slowly, we can undo the oppressiveness of ignoble silence and move toward speech that heals.

Ignoble silence can be a personal as well as societal problem. For many of us, it may be the way we hide from painful things within us. This is especially true if we’re dealing with heavy feelings of shame, despair, and trauma. Instead of embracing authenticity and vulnerability, we nurture a desire to disappear or recede. This is not another thing to blame ourselves for, but it’s something we must acknowledge when it happens. Silence can be used as another way to repress or avoid our deepest issues. The poet–activist Audre Lorde asked, “What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?”

Is your silence tinged with regret and loathing? This is not the noble silence of understanding and compassion, but fear-based and painful ignoble silence. Here, what we need isn’t more solitude, but less. We need to engage with ourselves and our experience and enlist the help and love of the people around us.

Wholesome and Unwholesome: Maturing Our Practice of Silence

In the end, we are not passive participants in our lives. Instead, what’s called for in every situation is wisdom. With clarity of mind, we can determine what is wholesome and what is unwholesome—and try to move our situation towards the beneficial.

This may require courage, and it may require assertiveness and vigor—to be able to point out when things are not right, to criticize what is worthy of criticism. And though we may need to do these things, we do them with the intention to help, not harm. We offer skillful criticism, the kind that’s given at the right time and place, with a mind of compassion.

Silence can be wielded skillfully or unskillfully. What determines the quality of our silence is our intention and the results our silence brings. Are we confronting or avoiding? Helping or hurting? Looking at or looking away?

This process of reflection helps fine-tune our discernment so we can see for ourselves how to act at any given moment. It’s all easy to look at mindfulness practice or the Buddha’s teachings and pick one aspect of the path to follow blindly. More difficult is to see how all parts of the path work together—the path requires not just wisdom but creativity, with plenty of room for error and forgiveness.

Ultimately, the silence we’re trying to cultivate is inner silence, the stability of mind that can be carried with us no matter what condition we find ourselves in. It’s a silence that’s joyful. A silence that is light. A silence that is kind.

The question, then, isn’t simply whether to be silent or not, but where, when, why, and how?

And if it’s a matter of being silent, don’t forget: We can be silent and smile.