The Red Book

by C.G. Jung

W.W. Norton, 2009; 416 pp.; $195 (cloth)

When I was an undergraduate, somebody’s aunt in her eighties came to stay with us for a couple of weeks. She was a Jungian analyst and every morning sat out under the Chinese elm tree in the garden for two hours, keeping company with her dreams and meditating. I knew my life was in certain ways foolish and even desperate, but around her I could feel light, grace, and forgiveness. That was my first exposure to Jungian work. Though it started out in psychiatry and still makes valiant attempts to board the mental health train, the Jungian work can probably best be thought of as a practice. It is a way of having, in a Western package, the sort of thing that Eastern religion gives you. It continues to interest us because its goal is not belief but transformation.

If you stop for a moment and look inside, you immediately notice the traffic in the mind. If you stop for a long moment, perhaps in a retreat, the surface effects fade and other odd things happen. You find yourself in forgotten memories and obsessions, and talking to people you don’t know or who are dead and so on. The navigation decisions you make at that moment are a determinant of your spiritual path. Jung chose to walk into this territory, and The Red Book is a vivid record of his travels and discoveries. It was also in a certain way the means of Jung’s journey.

Jung began The Red Book around 1912 and abandoned it around 1930. It is an illustrated account of his personal practice and discoveries and also, you might say, an account of how he got to be Jung. The book records an open-ended, exploratory, yet disciplined practice, conducted over many years by one of the great minds of the twentieth century. Sometimes he thought that he might be going mad but persevered; madness became a metaphor for leaving behind the world he knew.

Madness and spirituality have something in common, in that they both set in motion involuntary processes. Spiritual paths call it things like surrender and spontaneous healing and enlightenment. At the other end of the scale of involuntary processes are schizophrenia and mania. Jung knew a lot about madness and at the same time had a trust in the resources of the deep psyche that give us dreams, fantasies, visions, and symptoms. That trust and the courtesy with which he approaches the inner life is probably the main feature of his work, the thing that differentiates him most clearly from Freud.

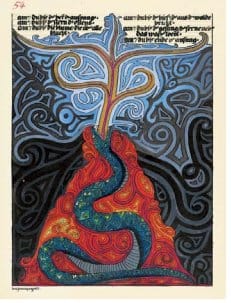

The practice that Jung records in The Red Book was to sit down and quiet his mind and see what figures of fantasy and vision came into his awareness. He would converse with them, then he would write about the encounter and paint the scene.

When you open The Red Book it is a shock—you have fallen into an involuntary process. It is first of all a visual experience. Jung wrote in different colors and sizes of German script, with elaborate initial letters on the page, as in an illuminated manuscript of the high Middle Ages. He painted trees and dragons, madonnas with child, mysterious veiled women, and men with wings. He painted lots of mandalas, which he saw as both diagnostic of the state of his psyche and as having an organizing capacity.

The problem of the period when Jung begins The Red Book, just before the start of the First World War, seemed to be that a certain kind of analytic thought process that left out much of reality was in charge of European culture, and that the parts of the psyche that were left out were taking revenge in irrationalism. Jung (in common with other prominent figures like Kandinsky) had terrible dreams of destruction overwhelming the land. We know now that Europe was heading toward a century of war.

In response, the idea of turning away from the off-the-shelf ways of understanding and seeking a deeper meaning for life was familiar in intellectual culture. Rilke was writing sonnets—which he received more or less as dictation—to Orpheus, Yeats was studying automatic writing, and Eliot was trying to educate his unconscious creative processes by immersing himself in great literature. Picasso was experimenting with Cubism. The Dada movement was for a while closely linked to the Jungians. The idea that something had to come from the depths was important.

Here is how Jung says it in The Red Book:

I have learned that in addition to the spirit of this time there is still another spirit at work, namely that which rules the depths of everything contemporary. The spirit of this time would like to hear of use and value. I also thought this way, and my humanity still thinks this way. But that other spirit forces me to speak beyond justification, use, and meaning. … The spirit of the depths took my understanding and all my knowledge and placed them in the service of the inexplicable and the paradoxical. He robbed me of speech and writing for everything that was not in his service, namely the melting together of sense and nonsense, which produces the supreme meaning.

This is not a book in which you can read five points and stroll away and apply them. In that sense it’s the opposite of a mindfulness manual. Its spirit has more in common with the late Buddhist sutras, with thousand-armed deities and paradoxes and impossible statements that nonetheless make you feel changed after connecting with them. Sometimes it is as if Jung is reinventing Buddhism and Taoism with very little prior knowledge of them.

Jung felt himself being stripped of his innocent and heroic ideas, just as people do in a meditation tradition. The force of the book is that it begins to take you on a journey, too. The charm of it depends on whether, like Jung, you have a feeling for the continual creative tension of a spiritual path beginning to open up, whether indeed you want to go on that uncertain journey into the depths.

Here is a passage in which he is being lectured by one of his vision figures:

The heroic in you is the fact that you are ruled by the thought that this or that is good, that this or that performance is indispensable, this or that cause is objectionable, this or that pleasure should be ruthlessly repressed at all costs. Consequently you sin against incapacity. But incapacity exists. No one should deny it, find fault with it, or shout it down.

This sense of the irreducible power in what is most humble was an important principle in Jung’s later work, when he turned to the tradition of alchemy as a metaphor for the smelting that goes on in human transformation. The humble was the dark, primary material of the inner work, as it was in the Taoist sources of Zen. Chuang Tzu said, “The Tao is in the ant, in the potsherd, in the shit and the piss.”

Jung’s work does touch me at a level deeper than the cognitive force of whatever he is saying. He doesn’t impress as a particularly good writer. Freud was a good writer—he won the Goethe prize for literature. But I read Jung because I have a feel for his creative conflicts, which seem universal. You can tell he took the journey himself and you go on it with him. That is how he is like a good Buddhist teacher.

Jung’s ideas that there is the image of a man in a woman’s psyche, and of a woman in a man’s psyche, and that the path through one’s own depths might mean embracing what you think of as your opposite, are now widespread in our culture. He talks with a convict:

Mustn’t it be a peculiarly beautiful feeling to hit bottom in reality at least once, where there is no going down further, but only upward beckons…?

One of the disadvantages of dream figures is that they can, in daylight, seem so overdone, more exaggerated than opera. It is their complex quality that makes Jung’s imaginary figures plausible. They are not necessarily cheering Jung on and they say interesting and surprising things. I remember thinking that understanding koans would make me more fearless and tougher, and I found it actually made me more emotional and, ultimately, more empathic. I remember at that time I was also very interested in working with dreams, and I had a figure of a woman appear, a kind of muse whose head was half turned away from me. I thought, “Well, I’ll have a shot at what Jung did. It would be nice to talk with the muse.” So I spoke to her. No response. “Probably I’m just not good at this,” I thought. But I took another shot: “Why won’t you speak to me?’ I asked the muse. It seemed to me like a huge effort at communication.

The response was immediate, unequivocal, and loud, “You never listen.” I had to admit that she was right. I just wanted her to perform when I wanted to write; I didn’t listen. This is another example of how, if you enter a relationship with your own involuntary process, something self-correcting might come into play. It’s not a rational path, but then neither are the Mahayana or the Vajrayana in Buddhism—they are in service of a deeper goal. The self-correcting quality in the figures is a clue that what we think we are is being dreamed in turn by a more profound layer of existence.

For many years I lived in an outpost of Jung’s world, working with people’s dreams, a peculiar and beautiful life. I worked in a room with a red Bokhara rug on the floor and a Japanese screen of wisteria on the wall. Dream figures filled the room. It was like walking inside stained glass or moving underwater. People would often tell me about their sex lives long before they would offer a dream or a vision. This was puzzling at first, but it came to me that, say, selling your body for cocaine is a kind of ongoing disaster, but in a sense public and uninteresting. A dream, though, is intimate and tells something about who you really are.

The deep psyche has an autonomy the way nature does. You have to work with dreams down at the dream level, or the presence goes out of the room. You can’t really say a snake means a penis or the veiled woman is the muse without dragging things up to a level at which they don’t breathe—the elephant in the zoo walking disconsolately in circles does not indicate her behavior on the savannah.

I found that the same was true of koans—you have to deal with them down deep where they come from, where it is dark, before explanations appear in the world, before the world appears. This is also of course true of love, death, and eating breakfast. Jung conveyed this really well.

Jung’s journey is interesting, harrowing, ridiculous, pompous, incomprehensible, amusing, sad, frightening, wise—the whole range of the human is there. Just like Buddhist practice.

Jung’s point of meeting with Buddhism is that, at a time when darkness seemed and was near, he offered the example of a trust in the deepest possibility of transformation, and in the involuntary processes that we contain, and in the depths of what it is to be human.

I think of meditation as the act of showing up for your life, the one you actually have, now. We can, Jung said, live a genuine life.