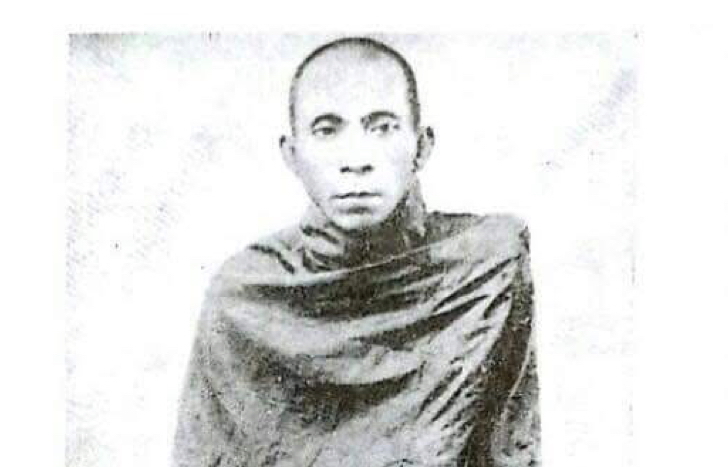

Venerable Adicca Vamsa, a dissenting voice and a prolific author, was controversially labeled a communist monk and a religious adversary and subsequently boycotted by the nationalist elements of the twentieth-century Buddhist monastic community of Myanmar. He fulfilled his monastic duty by offering guidance to the religious community and contributed to the anti-colonial struggle as a committed citizen. Consistently upholding his beliefs, even when unpopular, he grounded his advocacy in evidence and factual reasoning. As such, he represents a source of pride for the nation and Myanmar’s Theravada Buddhism.

His Youth & Buddhist Scholarship

Venerable Adicca Vamsa, originally named “Aung Myat Htut,” was born as the sole male child in his family. At the age of five, he began his education in basic Buddhist scriptures and traditional astrology under his uncle, Venerable Wilatha, a respected head monk in Yamethin. He became a novice monk at fourteen, taking the name Venerable Adicca Vamsa. His studies were put on hold due to the untimely passing of the head monk. At sixteen, he resumed his education by studying mathematics. Later, Venerable Adicca Vamsa continued his monastic education in Pyawbwe, learning advanced Buddhist texts and monastic discipline. At twenty-one, he was fully ordained, deepening his knowledge of Pali grammar, literature, Abhidhamma, and commentaries as well as Sanskrit grammar.

\In his fifth monastic year, having achieved his goal of mastering the Buddhist scriptures, Venerable Adicca Vamsa began teaching and writing scholarly works. He gained recognition for his insightful articles on the Pitaka (the “three baskets” of Buddhist scriptures; discourses, discipline, and higher doctrine), published in a local newspaper. In 1914, he arrived in Yangon together with over fifty monks and founded a monastic college. In 1918, one of his students from his college, Venerable Setthilabhivamsa, who later became a lecturer on Abhidhamma at the University of Yangon, achieved the highest rank in the state-sponsored Pali examination. However, a celebratory event was cancelled due to disagreements with patrons, a situation Venerable Adicca Vamsa recorded in a book. This event marked the beginning of his deliberate practice of chronicling his disputes in well-documented volumes, reinforcing his arguments with concrete facts and figures.

Reforming Society — The Case of Learning Foreign Languages

In 1918, at the age of thirty-one, Venerable Adicca Vamsa embarked on a nine-year journey to India, Sri Lanka, and England to study foreign languages. He mastered several languages, including English and Japanese, and traveled through Europe before returning to Myanmar in 1928. Upon his return, he expanded his monastery’s educational offerings by establishing a government-supported high school and a private English-language school. In 1931, his translation of Emperor Ashoka’s edicts into Burmese earned him the Prince of Wales Literary Award from Yangon University.

Venerable Adicca Vamsa emerged as a leading proponent of foreign language education for monks, a stance that provoked considerable resistance and ignited the first major dispute within the monastic order. His advocacy gained widespread attention among Burmese monastic circles worldwide following the publication of his book “The Guide on Bhasantara,” which urged the people of Burma — particularly young monks — to pursue the study of English. The conservative elements within the Buddhist monastic community and the ultra-nationalist elements within the anti-colonial struggle argued against it by accusing English of colonial and evil language, while Venerable Adicca Vamsa defended the idea by insisting that learning English is one of the necessary steps to becoming rid of British colonialism. Venerable Adicca Vamsa’s advocacy for English-language acquisition in the context of the anti-colonial struggle garnered support from several other influential progressive monks and local Marxist thinkers. This coalition of voices ultimately resonated with the broader public, contributing to a growing interest in learning English and other foreign languages.

Advocating Monastic Courts — The Case of Monastic Disputes

Venerable Adicca Vamsa later championed the self-governance of the monastic community in adjudicating internal legal matters, adhering to Buddhist monastic codes of conduct, except in cases involving criminal offenses. This advocacy for a distinct monastic court, working together with the existing juridical system was detailed in his book, “Legal Framework for Vinaya Practitioners.” However, this proposal again faced considerable opposition from conservative Buddhist and nationalist circles, sparking a nationwide debate within the monastic order and the wider Buddhist community. Venerable Adicca Vamsa defended his position in another book “The Treatise of Vinaya and Dhamma,” a work that continues to offer valuable insights for contemporary Buddhist reform movements.

Confronting Buddhist Gender Apartheid — Reviving the Bhikkhuni Order

Then, through his book “The Treatise of Bhikkhuni Sasanopadesa,” Venerable Adicca Vamsa tackled the issue of reviving the bhikkhuni order, which had been considered extinct for centuries in Myanmar’s Theravada Buddhism. This advocacy ignited the third and largest controversy among the monks, attracting global attention among Theravada Buddhist monks.

Rather than engaging with the broader movement for revival, critics focused on particular excerpts from Venerable Adicca Vamsa’s book that they deemed “blasphemous,” “anti-traditionalist,” and “anti-nationalist.” This backlash culminated in a massive public gathering in Yangon in 1935, attended by around 5,000 people and led by senior monks and political figures, where formal denunciations were issued against him. Among the attendees were prominent right-wing Buddhist nationalist leaders, including Thakin Kodaw Hmaing — a populist champion of peasant nationalism — Deedok U Ba Cho, then president of the Trade Union Congress of Burma, and Galon U Saw, who was a former Prime Minister of British Burma.

Following the collective resolution of the public assembly, Venerable Adicca Vamsa and his teachings were subjected to a widespread boycott and violent backlash, including incidents of stone-throwing. He was branded a communist monk, largely due to his reformist approach to Buddhist doctrine and his connections with notable leftist figures. Despite enduring official condemnation and public disapproval, he remained unwavering in his intellectual endeavors, continuing to lecture and publish. By 1931, his literary output had reached sixty books.

Even the outbreak of World War II did not deter him; he stayed in his monastery, dedicating himself to teaching and writing Buddhist scriptures. In 1942, at the age of sixty, Venerable Adicca Vamsa disrobed due to the opposition he was forced to endure, along with his declining health. No longer did he use his monkhood name but instead the Burmese name, U Aung Myat Htut. He married a student who had requested to take care of him given his health, and he dedicated his remaining years entirely to teaching and writing. He passed away in 1951 at the age of seventy, his body cremated at his former monastery.

Venerable Adicca Vamsa’s unsuccessful attempt to revive the bhikkhuni order within Myanmar’s Theravada Buddhism serves as a cautionary case study for reformist monks advocating for bhikkhuni rights in the country. It underscores the potential for them to become targets, not only of state authorities but also of reactionary Buddhist conservative groups employing mob rule tactics. Conservative monks and their political supporters often portray the resurgence of the bhikkhuni order as an influence of Western liberal or feminist ideologies, asserting that the bhikkhuni lineage in Theravāda Buddhism has long ceased to exist.

In contrast, Venerable Adicca Vamsa advocated for what he asserted was consistent with the original Buddhist teachings. These ultra-nationalist factions claim the Theravada bhikkhuni lineage has been extinct since approximately 100 BC, dismissing bhikkhunīs from the Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhist traditions as not genuine within the Theravada perspective. However, given that Mahayana schools across Tibet, China, Korea, and Vietnam largely adhere to the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya — historically a Theravada sect, particularly concerning monastic codes of conduct—bhikkhunis within the Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhist traditions possess a legitimate claim to authenticity from a Theravada historical standpoint even though their interpreting and literatures could be different in philosophical point of view.

Despite facing severe criticism and accusations of betrayal, communism, and posing a threat to Buddhism, Venerable Adicca Vamsa’s progressive stance on the revival of the bhikkhuni order has been vindicated by its subsequent re-establishment in Theravada Buddhist communities across Thailand, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka. His literary contributions continue to hold significant influence, particularly among monks pursuing international academic endeavours and advanced research degrees.

[Note: The name Venerable Adicca Vamsa represents the Romanized Pali spelling, while “Ardissa Wuntha” and “Addiccavamsa” could be considered more conventional renderings. Notably, Venerable Adicca Vamsa himself employed the spelling “Aditia Wamsa” in some of his published works.]