The largest church in the United States is a place of subtle power, and some surprises. Nestled among the stone and polished wood of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, on the Upper West Side of New York City, are statues of Gandhi, Einstein, and Martin Luther King, Jr. There is a triptych honoring the public artist Keith Haring and a poet’s corner celebrating Thoreau, Whitman, and Poe. The altar offers tributes not just to Christianity, but also to Islam, Judaism, and “Eastern wisdom traditions.”

Off the main altar is a locked sanctuary, a dignified space, quiet and subtly lit. It’s a columbarium, a room of small vaults containing urns. Each of the vaults is covered with a door of marble. Many are ochre, with touches of black and cream; graceful swirls reveal that the rock was once fluid and moving. One vault contains the ashes of members of Joan Didion’s family. Their names are engraved on the door, and there is space for one more. The space is for Joan Didion.

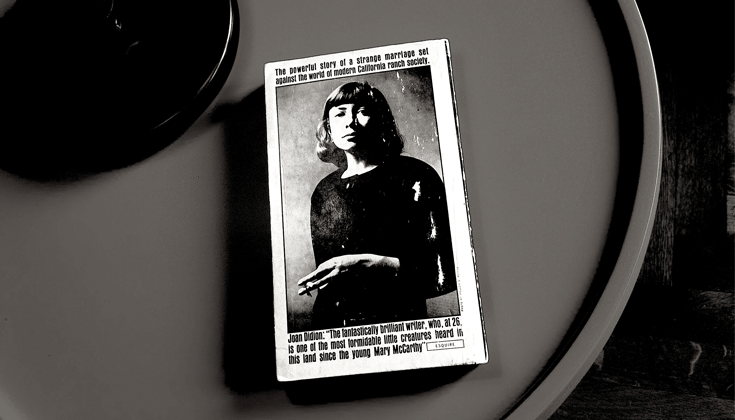

Didion was raised Episcopalian and remains a member of the church. A star of contemporary letters, she is deeply respected by writers, journalists, political thinkers, and cultural observers. Her thirteen books, including The White Album, The Last Thing He Wanted, and Slouching Towards Bethlehem, form a brilliant portrait of our messy, fascinating time. Yet nothing prepared readers for Didion’s most recent book, The Year of Magical Thinking. In it she turned her lens around, to observe herself during the year following the death of her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne. It was a time when she was, by her own account, “a little crazy.” Her mind was overwhelmed, all her usual reference points destroyed.

In a long conversation I had with Joan Didion, and a shorter meeting in New York, she was smart and gracious, dryly funny, and exactingly honest. She offered considered views of life and death, wisdom and love, some of them surprising even to those familiar with her work. Her year of magical thinking, she says, “didn’t really change my belief or non-belief. I still believe in geology.” Her grandfather, her mother’s father, was a geologist, and her view of the world, and her view of time, remain affected by what she learned from him as a child. She is comfortable explaining how rivers, hills, and coastlines came to be, and how they continue to change.

“I accept the Episcopal litany,” she says, “because it seems to me to embody geological truths: ‘As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end, Amen.’ ‘As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be’ means ever-changing, in my interpretation.” She offers a self-deprecating chuckle. “Which may not be the orthodox interpretation.”

She is not the kind of believer who holds firm to dogma when evidence and reason suggest a softer grip. “I don’t believe in a personal God,” she says, “a God that is personally interested in me.”

Didion’s interpretation of Christianity might be considered unorthodox in other ways, too. She is not the kind of believer who holds firm to dogma when evidence and reason suggest a softer grip. “I don’t believe in a personal God,” she says, “a God that is personally interested in me.” She also can appreciate Buddhism’s central tenet, the three marks of existence: impermanence, nonself, and suffering. “Nothing can bring satisfaction because everything changes, right?” she says. “Yes. And as far as the soul not existing, the soul doesn’t exist. I know Christians talk about it, but they just talk about it symbolically, don’t they? I have understood the entire thing symbolically. I mean, it makes a lot of sense to me symbolically. But it doesn’t if it’s supposed to be real.”

Needing comfort following her husband’s death, she reached for a favorite old book, a 1970 classic by Zen master Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. “A lot of times in my adult life, when I needed to cool out or simply feel better, calm down or get things into order, I would read again Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. I could do that and it would make me feel wonderful.” This time, instead of comfort, she discovered a hard truth about her own understanding: “I never got the lesson. I never acquired that emptiness. I would appear to be thinking along those lines, I would appear to be letting go. But I wasn’t at all.”

Struggling to get through each day, Didion came to understand more clearly than ever before that she too would die. Until then, her life would continue to offer more suffering, and more opportunity. The question became: how would she live now? Would she need more or less control, and could she learn to let go?

I would read Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and it would make me feel wonderful…. [But] I never got the lesson. I never acquired that emptiness.”

Joan and John were sitting down to dinner. He was having a drink; she was mixing a salad. They were talking, until he wasn’t. So she looked up—and the most ordinary thing happened. He died.

The room soon filled with paramedics, working furiously, talking in code. The hardwood floor was strewn with needles; there was a small pool of blood. They all rushed to the hospital, where the official pronouncement was made. The next morning she woke up, wondering why he wasn’t in bed.

During her year of magical thinking Didion could barely eat. She could not write. She had trouble sleeping. She was overcome by wave after wave of debilitating grief. Much of what she thought and said and did that year, even as she thought and said and did it, she knew was not rational. She was thinking like a child. What she wanted—and she believed, at some level, that it could happen—was to have her husband back.

Most of us presume grief has a pattern, a steady progression towards healing. Starting with the funeral, we expect to recover and adjust. John’s funeral service featured Gregorian chant, readings by friends and family, and a lone trumpet. Rituals were performed, his life celebrated, his death publicly acknowledged. But rather than a steady, upward progression, Didion found no pattern at all. “You’ve kind of been led to believe that there is a form to this,” she says, “but it turned out not to have any form. It didn’t resolve in any way.” Rather than move through it, “I think what happens is you incorporate it. You don’t get over it; it becomes part of who you are. What I mean is that you are a different person after that. I don’t know why this surprises me, since you’re a different person every day you live, but it does.”

Now, considering her husband’s death, she has again found the words to make the complicated clear.

A longtime fan of her work, I knew Didion could offer top-quality insights into contemporary politics and culture. Her eight non-fiction books and five novels consider big issues—power, corruption, the way we live now. She has stood up to political, military, and financial might to put facts in context and toss out myths. Now, considering her husband’s death, she has again found the words to make the complicated clear. Before the moment a loved one dies, she says in Magical Thinking, we cannot know “the unending absence that follows, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.” She goes on to say:

As a child I thought a great deal about meaninglessness, which seemed at the time the most prominent negative feature on the horizon. After a few years of failing to find meaning in the more commonly recommended venues I learned that I could find it in geology, so I did… I found earthquakes, even when I was in them, deeply satisfying, abruptly revealed evidence of the scheme in action.

Later, after I married and had a child, I learned to find equal meaning in the repeated rituals of domestic life. Setting the table. Lighting the candles. Building the fire. Cooking. All those soufflés, all that creme caramel, all those daubes and albondigas and gumbos. Clean sheets, stacks of clean towels, hurricane lamps for storms, enough water and food to see us through whatever geological event came our way.

That I could find meaning in the intensely personal nature of my life as a wife and mother did not seem inconsistent with finding meaning in the vast indifference of geology; the two systems existed for me on parallel tracks that occasionally converged, notably during earthquakes. In my unexamined mind there was always a point, John’s and my death, at which the tracks would converge for a final time.

She had some idea of how this might come about. One possibility was a favorite swimming hole. “We could have been swimming into the cave with the swell of clear water and the entire point could have slumped, slipped into the sea around us. The entire point slipping into the sea around us was the kind of conclusion I anticipated. I did not anticipate cardiac arrest at the dinner table.”

She was astounded by how ordinary John’s death had been. How life can change just like that: in an ordinary instant. She became fixated on this point. For months she could not get the word “ordinary” out of her mind. Observing her thinking during a painful year, Didion wrestled with her habitual need to be in control. She has described herself as being “born fearful,” and throughout her life has sought relief for nervous tension. Finally she came to a difficult realization: “I couldn’t control everything; I did not have that power. In fact, I could control nothing at all.”

It was not until nine months after John’s death that Didion sat down to write out the experience, as a way to understand it. When her notes lengthened and gelled and began to form a book, she thought it might be popular with widows.

The Year of Magical Thinking is not a self-help book. Nor is it a tome by an expert. In it we take a voyage to a frightening place, with a highly observant guide who is stumbling through. “I remember after I put my mother’s ashes in St. John the Divine,” she tells me, “for maybe a year I would have this recurring dream that I had an apartment in St. John the Divine. They would lock the front doors and the side doors at six o’clock, and so I had to be in the apartment by six o’clock. The dream didn’t go anywhere, but it was still affecting in some way. It was obviously about after death. And it had nothing to do with what I actually believe happens after death. I don’t believe that I will be conscious after death.”

Didion had great confidence in the quality of her mind. In her schooling and chosen career, she trained and sharpened her mind to be strong and true. The training began as an English major at Berkeley in the 1950s, when the English department practiced New Criticism. It was a spartan perspective of seeing exactly what was on the page, untainted by preconceptions or expectations.

“You were practically forbidden to consider the author,” she says. “What you were supposed to do was close textual analysis, just look at the text—at exactly what’s there—and not bring anything to it.”

In Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki Roshi offers a similar view. “When you listen to someone,” he says, “you should give up all your preconceived ideas and your subjective opinions, just observe what his way is… Just see things as they are with him, and accept these. This is how we communicate with one another… A mind full of preconceived ideas, subjects, intentions, or habits is not open to things as they are.”

During her magical year Didion stopped believing that her perceptions were true. Instead she watched, usually calmly but occasionally panicking, as her mind produced one crazy thought after another. Knowing this was so didn’t mean she could stop it: she was both groundless and without power. “One thing I learned is how fragile sanity is,” she says now. “How shallow it is. You don’t have a long way to go before you suddenly find yourself thinking in crazy patterns.”

She has reported on death squads in El Salvador and the worst of Washington politics; she is an observer famous for strength and courage. Now, though, she is in a place that is soft and raw.

Talking with Joan Didion you get a sense of the subtlety of her thought, of how sensitive she is. You can see her vulnerability acutely, the degree to which she is exposed. She has reported on death squads in El Salvador and the worst of Washington politics; she is an observer famous for strength and courage. Now, though, she is in a place that is soft and raw.

On the night John died, they had just come back from visiting the hospital where their daughter Quintana, then thirty-seven, lay in a coma. Quintana remained seriously ill for much of the next twenty months. Then she, too, died. Didion lost her husband, followed by her only child.

The apartment Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne shared on the Upper East Side of Manhattan is a short walk from Central Park, and just inside the park is an outdoor stage. Scheduled to give a reading there from The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion expresses misgivings. She jokes that she might need a band to back her up. The star attraction is usually musical—Bonnie Raitt, Balkan Beat Box, or Ani DiFranco—not a seventy-one-year-old woman reading about the death of her husband.

Married for forty years, she and John were rarely apart. They started every day with a walk in the park, worked in offices in the apartment through the day, and often emerged at night to dine out with friends. Once, when they were living in L.A. and she had to overnight in San Francisco, John flew up for dinner.

“They often finished each other’s sentences,” fellow writer Calvin Trillin told me. He is the unnamed friend in Magical Thinking whom Didion thanks for riding his bicycle up from Chinatown every day for weeks with the only food she could stomach, ginger congee. “John was enormously proud of her. If Joan won a prize she wouldn’t say anything, but John would call. He wasn’t just her editor, but her booster.”

Walking out on stage, Didion looks tiny and frail. (Trillin has famously said, “She is tougher than she looks, but then anyone is tougher than she looks.”) She is barely tall enough to reach the top of the podium; just her head pokes above it. She begins to read in a soft, precise voice. More than seven hundred people—two-thirds are women; most are under thirty-five—pay close attention.

On my flight to New York I had sat beside a woman who said her husband of fifty-one years had passed away the year before. When I mention Didion’s belief that we are not allowed time to grieve, her eyes fill with tears. “After just a few days,” she says, “even friends don’t want to hear about it. They would rather you act ‘normal.’”

Normal has never been acceptable to Joan Didion. Normal suggests a lack of curiosity, laziness, an unseeing eye. Nor has she time for cynicism or dreaminess. She scratches away at actual experience, to reveal its context and roots. Part of her philosophy, she says, is this: how much we learn in life is based on our ability to be self-aware. “If you don’t know what you’re learning, you’re not learning it,” she says. “I mean, if you can’t register what the experience is, the experience hasn’t happened in a way.”

Normal has never been acceptable to Joan Didion. Normal suggests a lack of curiosity, laziness, an unseeing eye.

The reading’s moderator, Philip Gourevitch, editor of The Paris Review, told me he admires Didion for her “incredible clarity in a plain American voice.” She has, he says, “an unflinching gaze for looking at things. She’s not interested only in how something presents itself, but what’s really there.” It is a rare writer, Gourevitch points out, whose magazine pieces are being read forty years later, both for the quality of the information and as enduring literature. Didion achieves her remarkable clarity, he says, because “quite often she is cutting through conventional wisdom, preconceptions, and misapprehensions. She makes the whole process of thinking part of the process of observation and comprehension.”

For the reading in Central Park, Didion has selected pages from early in The Year of Magical Thinking. She is coming home from the hospital with her husband’s wallet, keys, and clothes. Alone.

I remember thinking that I needed to discuss this with John. There was nothing I did not discuss with John. Because we were both writers and both worked at home our days were filled with the sound of each others’ voices.

I did not always think he was right nor did he always think I was right but we were each the person the other trusted. There was no separation between our investments or interests in any given situation. Many people assumed that we must be, since sometimes one and sometimes the other would get the better review, the bigger advance, in some way ‘competitive,’ that our private life must be a minefield of professional envies and resentments. This was so far from the case that the general insistence on it came to suggest certain lacunae in the popular understanding of marriage.

That had been one more thing we discussed.

What I remember about the apartment the night I came home alone from New York Hospital was its silence.

Unexpectedly, it starts to rain, but few rise to leave. Instead, hundreds of people take out newspapers, unfold them, and use them for hats. Twenty minutes later the rain picks up, becomes a pounding storm, and an organizer announces the evening will be cut short. Still, Didion will sign books in a nearby tent.

More than two hundred people wait, soaked and cold in driving rain. When they finally reach the signing table, many are beaming. One young man hands over a Dutch copy of Magical Thinking for her signature; another copy is Portuguese. One teenage girl tells the writer she is “the awesomest.” Through it all Didion sits: tiny, quiet, smiling a small smile. Even.

Trillin, just back from a national tour for his latest book, says he is surprised by how many people have told him they had read The Year of Magical Thinking. “Writers often don’t quite anticipate who’s going to read them,” he says. “She hit a chord.”

It’s true. After decades of writing for political junkies and culture critics, Didion is suddenly speaking to a wider audience. The Year of Magical Thinking won the National Book Award and is being made into a Broadway play, starring Vanessa Redgrave. Sales of hardcover copies of the book are about to surpass 600,000.

This suggests a need that is not being fulfilled. Our culture’s worship of youth is disconnected from common experience. We need a serious discussion about the end of life—and those left behind. Looking for help in the literature on grief, Didion found—as so many people do—that much of it is trite or otherwise unreadable.

Death, Didion says, is the one thing “we refuse to think about, refuse to contemplate, and refuse to admit happens.” She can recall proof of her own fear. When John and Quintana were sitting in the living room discussing the organ-donor forms on their driver’s licenses, Didion rushed in to change the subject. She couldn’t stand to listen to them; the thought of their dying was too painful. John’s certainty that he would die of a heart attack, and his history of heart trouble—these too she refused to accept.

Denial of death in our society has reached the point, Didion says, where we share this common belief: “Somehow you’re at fault if you die.” Following John’s death she experienced both blame and guilt. “You berate yourself. The survivors are among those who are afflicted by this belief that ‘they did it to themselves,’ or ‘I could have prevented it.’ There’s still a feeling, an inchoate assumption that if you’re living right, if you’re taking care of yourself, you won’t die.”

She is mystified that the denial of death has us so firmly in its clutches. “It’s very peculiar because this denial occurs most often in Christian nations, but death is at the very center of the Christian story. ‘He that believeth in me shall never die.’” Of course resurrection is at the center of the story, too, “but it’s not a literal resurrection,” she says. “After death I don’t think you’re aware of what John called ‘the eternal dark.’ I don’t think you are you.” And although we know better than to nurture them, she says, “we still have primitive beliefs.”

Didion says the book’s unexpected popularity can partly be explained by demographics: baby boomers are starting to reach an age when people they know are dying, and they are finally becoming aware of their own mortality. She is pleasantly surprised to discover that some people are reading Magical Thinking not so much for its insights into life and death and grief and dying, but because it is uplifting and offers something to aspire to.

“What surprised me when traveling with it” she says, “was the number of very young women who came up to speak to me in airports and other places. I realized at some point that they were reading it as a love story. They were reading about a marriage.

“That he died was just a cautionary tale.”

Just south of Central Park, 57th Street does not look like the site for an epiphany. Fifty-seventh between Fifth and Sixth Avenues is neither famous nor striking; by Manhattan standards it is a drab block. It is ordinary. Yet it was here that Joan Didion, several years ago, witnessed what she calls an apprehension of death. In Magical Thinking she describes “an effect of light: quick sunlight dappling, yellow leaves falling (but from what? were there even trees on West 57th St.?), a shower of gold, spangled, very fast, a falling of the bright.

Her apparitions of death did not make her fearful. On the contrary, they provided some measure of assurance.

She believes what she saw is death. “It was so beautiful,” she says now, “and so inexplicable in some way. I assumed that I was having a stroke, but I wasn’t.” A few years before she had had an earlier vision of death: “an island that was all ice, and glittering like a crystal. They were both very beautiful images.”

These apparitions of death did not make her fearful. On the contrary, they provided some measure of assurance. There’s a connection, Didion says, between two common problems: the way we deny death and the way we do not fully appreciate life. Instead of working to pass through the fear found within ourselves and perpetuated by our culture, we try to ignore it, hoping the paradox will go away. “If we didn’t deny death we would know how brief our moment is alive,” she says. “To some extent it would be difficult to function if we really appreciated how brief that moment is. Which is why people don’t do it.”

Only a small minority strive to live fully aware of impermanence. “If you could reach an acceptance of that and not be undone by it, well, that’s where you should be, I guess.”

Seeking clarification, I offer this: we all view life as solid and permanent, and we look at it that way to deny death. But the way to open up and fully embrace life is by accepting that life is transient.

“Yes,” she says. “I think that’s absolutely right.” It fits with her geological truth. “What I believe in is the permanence of the impermanence.”

Most of the time these days Didion is home, and alone. Her apartment is the best place to focus on what she must do now. “Immediately after John died people were always around, and it was a good thing,” she says. “Then I began to feel very strongly the need to have time alone, just to find order—in my own mind. So that’s what I’m doing now.”

The events of the past few years have, inevitably, affected Didion’s view of her own death. “It’s made it much more present as a concept. I mean, everything that’s happened in the past few years was terrible, but was also, in some odd way, quite liberating. You know that song, ‘Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose’—it’s liberating in that sense. You’ve seen the worst and you’ve lived through it. So it’s not going to get worse. It’s liberating to people who have a lot of anxiety and are apprehensive, which I have always been.

“I’m not so apprehensive any more, and not so anxious.”

Sometimes at home she reaches for Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, the book she first turned to for comfort almost forty years ago. Only now she is reading it not just to feel good. She is pondering its wisdom, especially what it says about letting go. After decades of missing its meaning, she is opening up to it. “I think now I get the lesson,” she says. Catching herself and chuckling, she adds, “I don’t get all of it.”

Getting the lesson, Didion says, is a work in progress. And applying it to life is tricky, too. “I have yet to successfully apply it. I seem to be in a morass of things undone. I don’t seem to be able to let go enough to either decide not to do things, or to do them and move on. Part of it is that I’m still grieving, and part of it is that during the past couple of years I got quite seriously behind. If you don’t do something every day you tend to become afraid to do it, and to some extent I don’t feel quite as capable as I did.

“But that’s not a lack of control; it’s just a lack of practice. Now I’m putting energy into trying to get back in charge, without being in control. Getting back in charge just means cleaning out my life, simplifying. It doesn’t necessarily mean trying to control it.”

Letting go, she says, is necessary throughout life. “You have to. You have to because everything changes. It’s the hardest thing to learn. It’s the hardest thing to do.”