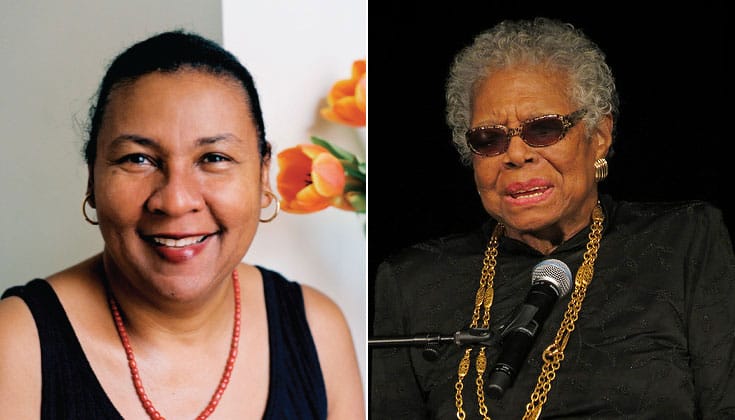

Probably the best part of my job as editor of Lion’s Roar is getting to meet some truly wise people and to listen in on their remarkable conversations. Here is a heart-to-heart, mind-to-mind exchange between two people, both important African-American women writers, who care and think deeply about life.

I must confess I knew little of Maya Angelou until we began to prepare for this interview. I had missed her famed inaugural reading that moved so many; I had not read any of her best-selling writings. I discovered a writer of well-crafted simplicity, and a person who, after a hard, varied and fascinating life, has come to a profound sense of responsibility. She was a true elder of our society, a teacher bringing a helpful, positive message to millions.

bell hooks is a kind friend to Lion’s Roar, and I only become more and more impressed with her passionate thought and writing. bell is someone who shows that the true life of the mind is not one of disinterested speculation but one of questioning that consumes the whole person, full of emotion, often painful. Listen to two people who know in their bones that life truly matters.

—Melvin McLeod

Maya Angelou: Good morning, bell. How are you?

bell hooks: I’m great. I finished reading lots of your work yesterday and I was just so excited by it. I love the work of women writers who have gone before me, like yourself, who have been bold in their vision and in their speech. In your book of essays, Even the Stars Look Lonesome, you say, “We need art to live fully and to grow healthy.” Talk about that.

Maya Angelou: That’s true. I do believe that art is as important to the human psyche and physical body as air is, as oxygen, as water. And alas, because it’s not something we can quantify reliably, we tend to think art is a luxury.

Art is not a luxury. The artist is so necessary in our lives. The artist explains to us, or at least asks the questions which must be asked. And when there’s a question asked, there’s an answer somewhere. I don’t believe a question can be asked which doesn’t have an answer somewhere in the universe. That’s what the artist is supposed to do, to liberate us from our ignorance.

bell hooks: Well, you do that for millions of people. I was writing in my journal last night, just writing down sentences from your work that I liked so much. I feel that often your writing is deceptively simple. One might think, “Oh, this is just easy reading,” and then there’ll be a line that makes you sit and ponder for a long time. For me, one of those is where you’re talking about the need for solitude and the need to stay away from company that betrays you, that corrupts you, and you have that wonderful line, “It’s never lonesome in Babylon.” I read this line to so many people, and I thought about how we need to make children feel that there are times in their lives when they need to be alone and quiet and to be able to accept their aloneness.

Maya Angelou: Yes, yes. Well, again, the writer is always peeking at the inner meaning. However, Nathaniel Hawthorne says, “Easy reading is damn hard writing.” So sometimes the critic will say, “Maya Angelou has a new book and it’s very good, but then she’s a natural writer.” Well, being a natural writer is like being a natural open heart surgeon. I labor over every sentence. I labor to make it seem simple. I would like to have a reader thirty pages into a book of mine before she knows she’s reading. I would love that. I will work on a paragraph for two days, three days, to keep it simple. I’ve been signing books recently, and people will walk up to me with a book and say, “I read it in the line.” I’m torn by that, because I’m glad the work is accessible, but on the other hand, it took me a year to get that together and they read it in the line! (Laughs.)

bell hooks: Some people act as though art that is for a mass audience is not good art, and I think this has been a very negative thing. I know that I have wanted very much to write books that are accessible to the widest audience possible.

Maya Angelou: Yes, indeed. When Romar Bearden or John Viger or Artis Lane do their paintings or sculptures, they mean for the art to be inside the people, whether they think about it consciously or not. Elizabeth Catlin wants her work inside people. So nobody really wants to write dust-catching matter, nobody. Every artist wants to say, here it is, if you can internalize it, if it can be of any use to you, then my work has not been in vain.

bell hooks: You’re constantly encouraging people to read, and not just to read your books but to read a wide variety of writers—to read the great white male writers, to read the great African-American writers of both genders. I think that’s a force that we see in everything you’ve done—praise for the power of reading to transform our lives.

Maya Angelou: I remember myself as a young girl in Arkansas in the lynching days of the thirties. One man was lynched in my town and people took pieces of his skin for souvenirs, because he was burned after he was lynched. My grandmother was kind of the mother of the town, mother of the black part of town, and she heard about this and we prayed and prayed and prayed. Every time she’d think about it—”On your knees.”

In the meantime, I was reading Charles Dickens, and Dickens liberated me from hating all whites all the time. I knew that I liked some of these people, because I felt for Oliver, and I felt for Tim. I read the Bronte sisters and I felt for those people. I decided that the people in my town were a different race than the whites on the moors and in the poor people’s homes and in orphanages and prisons. So I was saved from hating all whites, you see.

bell hooks: When I read Wuthering Heights as a working class girl struggling to find herself, an outsider, I felt that Heathcliff was me, you know? He was symbolic to me of a kind of black race: he was outcast, he was not allowed into the center of things. I transposed my own drama of living in the apartheid south onto this world of Wuthering Heights and felt myself in harmony with those characters.

Maya Angelou: Absolutely.

Melvin McLeod: It strikes me you are suggesting that reading is a more powerful way to develop empathy with people of different races or classes or times than even our normal day to day relationships.

bell hooks: Well, this is so because reading requires that you have to use your imagination. When I’m reading Wuthering Heights I have to imagine what Heathcliff looks like, I have to imagine what Katherine is like. I have to imagine and so my mind has to be working.

Maya Angelou: The act of reading demands and commands all the senses. I was teaching “The Highwayman” not long ago and I got to the point where the highwayman goes into the courtyard, and it’s night, and the moon was a galleon, and the road was a ribbon of moonlight, and…

“Over the cobble he clattered and clashed in

the dark inn-yard.

He tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all

was locked and barred.

He whistled a tune to the window, and who

should be waiting there

But Bess, the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love knot into her long black hair.”

Now this is the part where I ask the students to particularly be there:

“And dark in the dark old inn-yard a stable-wicket creaked

Where Tim the ostler listened. His face was white and peaked.

His eyes were hollows of madness, his hair like mouldy hay,

But he loved the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s red-lipped daughter

And dumb as a dog he listened…”

Now that, that, you have to read to hear that wicket creak, and to see this poor old ostler, mad as a dog, hair like mouldy hay—you can smell him. Oh, reading, it commands all our emotions, all our possible talents.

bell hooks: I’m so disturbed when my women students behave as though they can only read women, or black students behave as though they can only read blacks, or white students behave as though they can only identify with a white writer. I think the worst thing that can happen to us is to lose sight of the power of empathy and compassion.

Maya Angelou: Absolutely. Then we become brutes. Then we risk being consumed by brutism. There’s a statement which I use in all my classes, no matter what I’m teaching. I put on the board the statement, “I am a human being. Nothing human can be alien to me.” Then I put it down in Latin, “Homo sum humani nil a me alienum puto.” And then I show them its origin. The statement was made by Publius Terentius Afer, known as Terance. He was an African and a slave to a Roman senator. Freed by that senator, he became the most popular playwright in Rome. Six of his plays and that statement have come down to us from 154 bce. This man, not born white, not born free, said I am a human being.

I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else’s whim or to someone else’s ignorance. When I finish lecturing, I find that the whole audience, black and white, is a little bit changed, because I will have recited Sonya Sanchez, Anne Marie Evans, and probably Eugene Redmond, and Amiri Baraka, and Shakespeare and Emerson, and maybe talk about Norman Mailer a little bit, because he writes English, and Joan Didion, who writes this language. People see something. I don’t know how long the change maintains, but if you have changed at all, you’ve changed all, at least for a little while.

Melvin McLeod: Dr. Angelou, I’m extremely impressed with the values and the moral lessons that you bring to such a very wide audience. I think it is a very positive contribution you make to this society. As a writer, do you simply write for your own inner purposes, and let people take from it what they will, or do you have a conscious didactic purpose in your work?

Maya Angelou: Well, I think everybody has a conscious didactic purpose. I want to tell the truth. This is a very simple way of describing it. I will tell the truth. I may not tell the facts; facts can obscure the truth. You can tell so many facts you never get to the truth. Margaret Walker says you can talk about the places where, the people who, the times when, the methods how, the reasons why, and never get to the truth.

So I want to tell the truth as I see it, as I’ve lived it. I will not tell everything I know. But what I do say is the truth. Now that is at once for myself, but it’s also to be of use to and present with young people, who in many cases have been lied to so ferociously by the society and by their parents. They are told, oh, you shouldn’t make any mistakes, when in truth, it may be imperative that you encounter defeat so you can know who you are. I mean, what can you take? How can you rely on yourself? In my work I constantly say, this is how I fell and this is how I was able to rise. It may be important that you fall. Life is not over. Just don’t let defeat defeat you. See where you are, and then forgive yourself, and get up.

bell hooks: One thing that has happened for me is that I feel enormously blessed to be a successful black woman writer in this culture, but I have found my small fame, such as it is, to be very isolating. I was really happy to see you writing about some of the pitfalls of fame, because I think that especially for black women, the more we rise from the bottom, the more we move and journey, the more we are the targets of the most brutal and vicious attacks.

Maya Angelou: That’s true. The only thing I’d say is this: you’re also going to be attacked if you stay down there. So you may as well move. Everything costs, all the time, all the time. It costs to lose and it costs to win, so you may as well win, and do what you came here to do.

bell hooks: It seems to me a lot of Even the Stars Look Lonesome is about that power of journeying and crossing boundaries.

Maya Angelou: That’s it. I think that sometimes we become lethargic out of fear. It’s not really laziness so much as it is timidity. We’d rather bear the ills we have than fly to others that we know not of, when in truth the place where one is standing may be untenable, it may be dangerous, it may be stultifying, and it’s better to just step on. You know, you have to move.

bell hooks: Well, how has your stellar fame changed your life?

Maya Angelou: Well, let me speak of the few negatives first. The larger my name becomes, the more I am a target, yes. People sometimes put people on pedestals so they can see them more clearly so they can knock them off. There is that in the human psyche. Sometimes people are at your feet, and as the winds of fortune change, they’ll be at your throat. I understand that. What I do is I follow the advice of the West African philosopher, which is, “Don’t pick them up, don’t lay them down.” That is, when someone says, “You’re the greatest, you’re the absolute, you’re a genius,” you say, “Thank you so much, thank you, bye-bye, bye-bye.” Because if I pick them up, you see, I got to then believe when they say, “You’re nothing, you’re a charlatan, you’re a…” oh, some of the words, ugh.

bell hooks: Maya, over the years I’ve often been attacked by other black women writers, but you have always been incredibly supportive, incredibly loving. Could you talk some about the need we have to be nurtured by the writers who have come before?

Maya Angelou: It wasn’t difficult to be supportive of you because you’ve always, in every word, been so forthright. I think that may be what has alienated some people from you and your work because you were forthright in a time when…it was sort of like, you were country when country wasn’t cool (both laugh).

But I thought it was just the most wonderful thing in the world that you had such pizzazz. Even when you weren’t certain, you were confident. I know that sounds like a contradiction in terms, but it was very necessary to have your voice.

bell hooks: Sometimes I have felt so discouraged, particularly at the attacks that have come from black women peers.

Maya Angelou: Well, you have to realize that those attacks are fueled by, impelled by, jealousy.

Melvin McLeod: I’d like to raise the other side of this equation, which is not the criticism but the great respect and influence accorded you. When I was reading your essay, “They Came To Stay,” about the virtues of African-American women, I was struck by how prominent black women are among the moral examples and guides of our culture. There is yourself; there is Oprah Winfrey, who I think may be the most important spiritual teacher in America today; there is Alice Walker; bell’s work has a deeply moral character. What is it about the condition of the African-American woman that makes her so well suited for the difficult role of moral instructor, and willing to take it on?

bell hooks: Before Maya says something, can I just say that when you named off all those women, I realized what we have in common is not just that we’re black, but that we all came from harsh and difficult circumstances. We were on the bottom of this society’s class totem pole at some point in time. I think that is as much a factor as race, where we were positioned class-wise—and geographically, because those women, we were all southerners.

Maya Angelou: That’s true, very true. Well, there’s a sardonic line in a nineteenth- century blues song: “I was down so low, gettin’ up stayed on my mind.” Very true, too. There’s no place to go but up.

Also, there’s somebody who went before us. Those grandmothers and great grandmothers, and grandfathers and uncles and fathers, told us, “You’re the best we have.” This didn’t happen so much in bell’s generation, but in my generation one was told, “You represent the race.” And my goodness, that was a piece of a burden, and a wonderful chore, a wonderful charge. You have to go out there and represent the race.

So, one, we had very little choice about it, and two, there was a willingness, a volunteerism, to do the best you could.

bell hooks: Many spiritual teachers—in Buddhism, in Islam—have talked about first-hand experience of the world as an important part of the path to wisdom, to enlightenment. I think many black women writers have tried to create our philosophy, our theory, our artistic vision, from that place of experience, and I think anybody who does that is uniquely situated to speak to masses of people, to be a teacher in the great spiritual, prophetic sense of that word. When Maya Angelou tells a story, a story often coming from her own experience in the world, you see the ripple effect through the audience, the sense of connectedness. It’s storytelling that creates community.

I think that contemporary black women writers have been willing to risk telling things about their lives that other people haven’t been willing to tell. I sat with a group of women last night and I was telling them about Maya Angelou writing about sexuality for the over-sixty and the over-seventy. Everyone admitted that hardly anyone touches upon that. Maya begins from the place of her mother’s experience, and then from her experience; I think that willingness to share allows one to teach in a very different way.

Maya Angelou: Thank you. The idea that closing one’s eyes and sticking one’s head into the sand, as the ostriches are accused of doing, will make the bugaboo go away has never been one of the escapes for the black woman. We’ve had to see and admit what we see. Or we’d have been killed, we’d have been dead.

bell hooks: Well, how do you feel about the critics who have accused you of being a modern day mammy for the Clintons, for the nation? Can you talk about that some?

Maya Angelou: I can’t think of anything better (laughs).

bell hooks: Well, say more. I know your understanding of that is much more sophisticated than people will assume when you say that.

Maya Angelou: Exactly. What I mean is I take responsibility for the time I take up and the space I occupy. That’s what I do. And if that is considered being a mammy, well, I can’t do anything about their ignorance. I can’t de-ignorize them. So if I’m asked to speak for my church, or my neighborhood, or my people, I’m going to speak. I pay taxes. In all the ways I pay my dues. In all the ways.

I have a lot to say, so I speak. I’m sorry that folks find that negative and derogatory. I’m always extolling the human spirit, and sometimes the human spirit doesn’t want to be extolled. It wants rather to drag down the extoller. You know, when you say to someone, “You’re wonderful,” and they say, “I’m not that wonderful, stop saying that,” well, they tell me more about themselves than about me. Because what I see is the wonder in the human spirit. What I see is the potential in the human spirit. Some people will really try to live up to the level upon which you address them. Some can’t. Some resent being asked to come up, come up out of the morass, come out of the mire, come up, the air is breathable, up an inch out of self hate.

bell hooks: I was particularly struck by your critical reflection on your support of Clarence Thomas. I found it fascinating because I believe that this nation can only heal from the wounds of racism if we all begin to love blackness. And by that I don’t mean that we love only that which is best within us, but that we’re also able to love that which is faltering, which is wounded, which is contradictory, incomplete. In your “I Dare to Hope” piece you seem to be talking about the necessity of not giving up on people.

Maya Angelou: Absolutely. You see, I think we confess that we’re not very smart if we give up on people. I think that our pundits ought to have planned ways in which to go out to Clarence Thomas, to surround him…

bell hooks: That’s what I found fascinating in your piece, since I didn’t support him…

Maya Angelou: I understand. But to surround him with so much stuff that he’s almost a pupae in chrysalis, instead of shunting him away, closing him in. If we could have done that, surrounded him, eventually he might have emerged a butterfly. Now, he might have emerged a dragon, but I think the effort should have been made.

bell hooks: That really impressed me, especially in terms of thinking about the larger meaning of compassion. I feel I’m always trying to address the question of not dividing people into oppressors and oppressed, but trying to see the potential in all of us to occupy those two poles, and knowing that we have to believe in the capacity of someone else to change towards that which is enhancing of our collective well-being. Or we just condemn people to stay in place.

Maya Angelou: Exactly. And how dare we? How dare we? Now mind you, I wrote that piece before the revelation of the Anita Hill affair. But I’d like to think that I would still have written the piece.

bell hooks: I think this is a difficult question, how we deal with the question of forgiveness. For me forgiveness and compassion are always linked: how do we hold people accountable for wrongdoing and yet at the same time remain in touch with their humanity enough to believe in their capacity to be transformed?

I remember when the Mike Tyson/ Desiree Washington case was happening and people kept wanting me to choose, and I kept saying, well, I feel for both of these people. I feel this man should be held accountable for any actions he may have done; at the same time, I also feel for the culture he’s been raised in that has made him an instrument of violence. Increasingly in my life, I’m appalled at how people so desperately want to choose either/or, rather than to have compassion in a larger, more complex way.

Maya Angelou: Absolutely. The decision to choose the either/or way of being is the simplest…well, it’s not really the simplest but it’s the easiest way of dealing with life. And it rules out one half of life, of course. One half is ripped right down the middle, and that half is all fuzzy and out of focus and away somewhere, so the side I’ve chosen is the only side that has any value.

Some years ago Oprah asked me to talk to Mike Tyson when he was still with his wife, Robin, and I said if he will call me, I will talk to him. But he must ask. But he didn’t, and then years passed and he was in jail, and Bob Johnson from BEP and Bruce Lewis called me and said that Mike Tyson asked would I come to jail to visit him. So I went, and I had no idea what on earth I was going to say to this young man. I’d never been but once to a fight; it’s not one of my ways of spending my time.

I went in really nervous and this young man came out who was smaller than I expected. And he said, Dr. Angelou, I just want to thank you for coming to visit me and I just have a few questions. bell hooks, I hope you’re sitting down: he said, my first question is this, what do you think of Voltaire? (laughter) I said, not very much. I hadn’t thought of Voltaire in a million years. He said, but I mean really, what do you think? I said, well, Voltaire was a people’s writer, he was a people’s poet, and a people’s dreamer. He was brave and courageous. He said, well, how do you work out the Eurocentrism of, say, Tolstoi, and Voltaire, and maybe Balzac, with the Afrocentrism of James Baldwin and Richard Wright? (laughs) I started laughing. I started laughing, I got the biggest, greatest laugh. I said, this place has done you well. You’ve been reading. So we had a three hour talk.

bell hooks: I think that goes back to the place of solitude. I always tell my students that Malcolm X came both to his spirituality and to his consciousness as a thinker when he had solitude to read. Unfortunately, tragically, like so many young black males, that solitude only came in prison.

I often think, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we had camps, like summer camps, that grown people could go to where they could fellowship together with books. I was talking recently about whether Oprah’s book club was beneficial and someone pointed out that those of us who are writers and academics are accustomed to a world where we have someone else to talk to about what we read. But for most people, what is so painful about reading is that you read something and you don’t have anybody to share it with. In part what the book club opens up is that people can read a book and then have someone else to talk about it with. Then they see that a book can lead to the pleasure of conversation, that the solitary act of reading can actually be a part of the path to communion and community.

Maya Angelou: Absolutely. I remember years ago, I remember a writer, Jacqueline Susann, who wrote Valley of the Dolls and things like that. I found people really putting down those who read those books. On the other hand…

bell hooks: These books provided conversation.

Maya Angelou:That’s right, and also led to other books. Yes, indeed. It’s very important. And then, not only have you sunk a seed which will grow, but the very act of reading is in itself addictive.

bell hooks: At this stage of life, where do you find your joy? I struggle with that, Maya, with my joy and my pleasure. I often find it easier to be teaching or giving to others, and often struggle with the place of my own pleasure and joy.

Maya Angelou: Well, I find the teaching and the giving are joy. I walk out of a class sometimes on top of the world. And I have friends who love me and whom I love. They lift me up with their laughter, their jokes, and their pain sometimes. All of those things lift me up.

I’m trying to be a Christian, and that’s hard work. I’m always amazed when somebody says, I’m a Christian. I think, already? You’ve got it already? Trying to be a Christian is like trying to be a Muslim or a Buddhist or a Shintoist: it’s not something that you achieve and then you sit back and say, now I’ve got it. I’m trying to be a Christian in every moment. That also brings me great joy, and of course the concomitant misery, because according to my teaching I have to admit that everybody else is a child of God—the brute, the bigot, the batterer. I have to admit it, whether he or she knows it or not. So that challenges me, and when I can get over on that, it brings me joy. I love to laugh.

bell hooks: Yeah, I wanted to ask you about laughter, because when I think about the evenings that I’ve spent with you, one of the things is how much laughter there is, how much humor. While on one hand you are, as Melvin has been evoking, somebody who tries to share ethical values for how to live more fully and deeply in the world, I also know that you’re somebody who is totally capable of telling a great joke. Melvin keeps using the word moral, but I think ethical is a much more expansive word than moral, because ethical allows for the mistakes people make, and it also allows for the kind of moments I have shared with you of great ribald and bawdy humor.

Maya Angelou: That’s it!

bell hooks: …so that you’re not Maya Angelou trying to be this saintly person where everything has to be politically correct and nothing can be out of whack. In that sense I think of you in terms of Trungpa, the Buddhist teacher, who talked about laughter and play as central to our full humanity.

Maya Angelou:Yes, it’s central to balance. It’s central. I think that I’m always apprehensive around people who don’t laugh. I think, my god, what part of you is so tightly wound that you can’t laugh? What will happen when that spring breaks? What will happen? So, laughter.

There’s a line in the Christian bible that says a cheerful spirit is good medicine, and it’s been found that that is true physiologically—that with a cheerful spirit our glands do produce some more endorphins that go as sentinels and surgeons to help ailing parts of the body. For the mind, the spirit and the body, one must have laughter.

bell hooks: I think we’ll have just one last question, because I have struggled a lot about the times in our life when we want to pause. Here you are, Maya, you’ve given so much, you’ve been a prophet, you’re a messenger. What happens when you just want time out? Do you think that there’s a place for us to say, well, I want to take six months and be quiet?

Maya Angelou: Mmm…well, my time for that has just about passed. I might have done that in my fifties, or maybe early in my sixties, but in a few months, I’ll be celebrating my seventieth, and I feel the hot breath of time on the back of my ear, you see, so I think I’ll just keep on pressing.

bell hooks: Well, I hope to have the opportunity to celebrate this seventieth with you.

Maya Angelou: Thank you very much. I will certainly invite you.

bell hooks: Thank you. It’s been great to talk with you. It’s always wonderful. You know what they say about there being a sweet, sweet spirit in this place? You always bring a sweet, sweet spirit.

Maya Angelou: Thank you, my dear. It’s lovely. I’ve been looking forward to this, and it’s better than I hoped.

Melvin McLeod: I’m so glad that you two were able to do this. I very much appreciate it. Thank you.