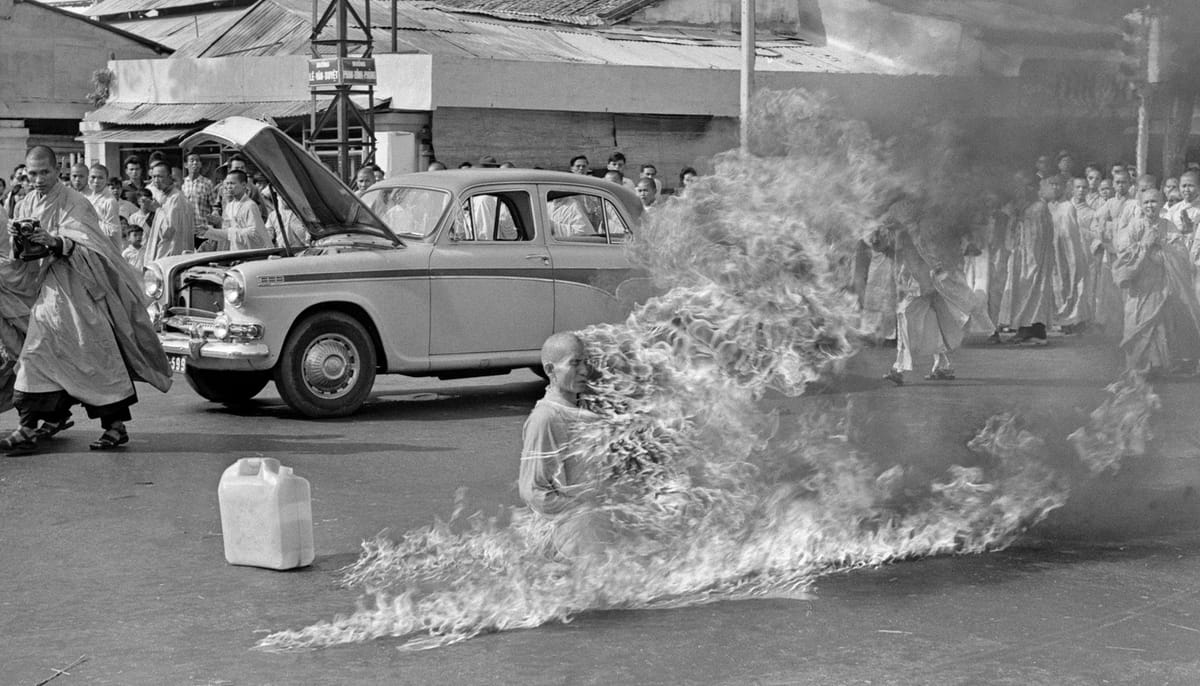

Fifty-five years ago, on June 11, 1963, in a heavily trafficked intersection in downtown Sai Gon, the 67-year-old Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc self-immolated.

Thich means “most revered” — a title given only to spiritual masters. From his home pagoda, Quang Duc drove hundreds of miles to the intersection in Sai Gon. There, he poured fuel on himself, sat in the lotus position, and lit a match. It was an extreme act in the Buddhist tradition of taking all suffering upon oneself to protest the suffering of others.

Quang Duc’s protest was against the corrupt regime of Ngo Dhin Diem, who controlled South Viet Nam. All the while, his disciples prayed and made a cordon around him to prevent police interference while taking beatings on themselves without striking back — as the master taught.

Today, a new memorial stands on the street corner where it happened, showing him sitting peacefully amidst the flames. Every year for the past eighteen years I have led a group of veterans and civilian pilgrims on a healing and reconciliation journey to Viet Nam (out of respect, I write “Viet Nam” and “Sai Gon” as two words, in the Vietnamese style). We visit the site, meditate, pray, and ask what Quang Duc’s sacrifice teaches us. During my first visit, almost two decades ago — when the memorial was just a simple marble relief of the monk in meditation — I lit incense and bowed before the altar. Quieting, I heard these simple words:

When I burn

let me sit.

It is most difficult to sit through our pain, sorrow, and suffering, without rising up, striking back, or rejecting it from our hearts through rage, denial, blame, or heedless actions. Buddhism teaches that we should express no violence to any being. It is perhaps our greatest challenge to accept our own pain rather than channeling it back into the world.

Quang Duc’s gesture was surrounded by violent protests. It’s true for all of us that we are surrounded by chaos and violence, challenged to keep our still center. He did.

During my most recent visit, last November, I asked in my heart: How can we tolerate the terrible and overwhelming violence and abuse that haunts our countries and our planet today? This time, on the busy urban street corner — made sacred by Quang Duc’s sacrifice — I heard these words:

Only universal love

transcends endless suffering.

The night before his sacrifice, Malcolm Brown — a photojournalist with the Associated Press — received an anonymous phone call telling him to be at the street corner the next morning to witness “something important.” He was there to snap the photo of Quang Duc that shocked the world. And it still does.

Brown’s photo became one of the three most iconic and influential of the war. A second was of Kim Phuc, the schoolgirl running naked and in anguish as napalm scorched her body. The third was of a South Vietnamese officer as he pulled the trigger and shot a helpless and restrained prisoner in the head. At the time, these photos mobilized anti-war sentiment around the world.

In the fire, he remained calm, accepting, and immovable.

Here in America, there’s a popular misconception that Quang Duc’s sacrifice was primarily to protest the immoral war that our country, the United States, was waging with increasing cost and violence. This was certainly in the mix of his motivations. But it was not his primary drive.

Diem’s regime was rife with corruption and vicious in its use of police and military violence to stem resistance, maintain power, and control the economy. The Northern Vietnamese called it a “puppet regime” — an unpopular Catholic president, supported by the United States with pressure from the Catholic Church to promote Catholicism in Southeast Asia. Diem rejected and oppressed the country’s Buddhists while the northern communists rejected all religion. Quang Duc was defending Buddhism in the most commanding way he could: willingly suffering, and dying, so others would see his community’s pain.

As he burned alive, Quang Duc sat. He never cried out, but softly chanted Buddhist sutras. As his body turned to cinder and began to collapse, he reached out an arm to push himself up and keep chanting. In the fire, he remained calm, accepting, and immovable.

Since Quang Duc’s demonstration, thousands of protestors have self-immolated for various causes, including more than a hundred Tibetans who have burned themselves alive in protest of their homeland since 2009. The Dalai Lama has discouraged Tibetans from such acts, as self-immolation today garners little attention from the media, and often the demonstrator is left alive but horribly maimed.

There is one more part to Quang Duc’s story — little known, but remarkable. After the police took Quang Duc’s remains, tens of thousands of Vietnamese rose up in protest, forcing them to turn the monks remains back over to the Buddhists for a proper ceremony. The master’s followers reburned his scant remains. At the end, left in the ashen heap, was a heart — black and solid. It had turned to stone and remained behind.

The stone heart was taken to the Vinh Nghiem Pagoda in Ho Chi Minh City and placed in a special vault. It is preserved there to this day, taken out once a year during a most solemn ceremony.

Bo Tat means bodhisattva in Vietnamese. A bodhisattva is a being who reaches enlightenment, yet refuses it in order to remain among humanity until we are all enlightened together. Bo Tat is one who could leave, but stays and suffers for the rest of us. The people of Viet Nam have conferred the title of Bo Tat to Quang Duc. As I sat at the corner, I heard, as if from Quang Duc himself,

You must love life and this world so much — open your heart so wide — that your personal suffering does not matter. Open your heart so wide that it encompasses the world and all that is in it — even those who have hurt or wronged you.

These are difficult lessons, I learned from my time in Viet Nam. There, the people I met greeted me with love despite the horror my countrymen visited upon them. Today, I believe that as we face and heal our own troubled times, we must seek to achieve such love.