One of our Western sutras is the children’s round that goes:

Row, row, row your boat

Gently down the stream.

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily,

Life is but a dream.

The image of a human life as a small skiff on the wide waters of the world has been around as long as people have had boats, and the thought that life is a dream is no news flash either. But what does it mean that there is something happy, maybe even beautiful or consoling, in thinking so?

The founding myth of Buddhist tradition—the life of Siddhartha, who became the Buddha—has something to say about this. Here’s the story, as I understand it.

“A long time ago there is a green and pleasant land nestled in the foothills of the Himalayas. The queen’s name is Mahamaya, which means the Great Dream of the World. One year, during the midsummer festival, Mahamaya herself has a dream: The Guardians of the Four Quarters lift her up and carry her high into the mountains. They bathe her in a lake and lay her on a couch in a golden palace on a silver hill. A beautiful white elephant, carrying a white lotus in his trunk, approaches from the north and enters her right side, melting into her womb. When she awakens, she knows that she has conceived. The priests interpret her dream to mean that if her child follows the householder’s life, he will become a great king, but if he follows the spiritual life he will become a buddha.”

(Looking back, people realize that at the moment of this conception, people began to speak kindly to each other, musical instruments played themselves, and every tree burst into blossom.)

“When she is about to give birth, Mahamaya sets out for the place she was born, as is the custom. Along the way, she stops in a grove of trees to rest. She stands on the roots of a great tree, and as she reaches up for a branch to support herself, she gives easy birth to a son who will be called Siddhartha. Seven days later Maya dies and is taken into the heavenly realms, where she watches the rest of his life unfold.”

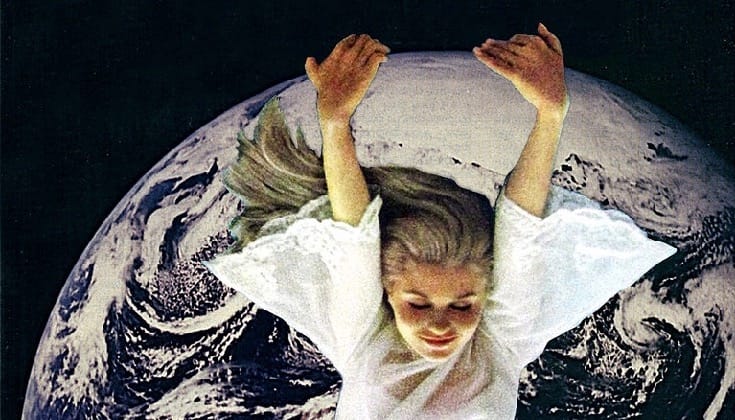

There is the sense that the world is endlessly imagining itself into existence, endlessly generating the specific and individual things of which it is made.

This story begins with a dream rising within a dream: Mahamaya, the great dream of the world, steps from the hubbub of life into her quiet apartment, where she has a dream. She is taken someplace new, someplace she’s never been before, to conceive of something never conceived before. It is a blessed moment, a sudden upsurge of beauty and kindness in the world. The following spring she gives birth to another dream, an individual named Siddhartha.

In this passage there is the sense that the world is endlessly imagining itself into existence, endlessly generating the specific and individual things of which it is made. The Chan teacher Great Master Ma used to say that the universe is the samadhi of dharma nature, out of which no being has ever fallen; in other words, the universe is the deep meditative state of the universe itself, which contains all things. But this deep meditation doesn’t just hold everything; it actually becomes earth, wind, flame and water, and then mountains, rivers and trees, skin and bones, flesh and blood, as Zen teacher Keizan Jokin added. You and I and the teapot on the table between us are the samadhi of the universe.

In meditation we can fall through the bottom of our individual states into this deep meditation of the universe-as-a-whole, like individual waves sinking back into the ocean for a while. It would be more accurate to say that we don’t fall or sink anywhere, but simply remember what is already and always true. And the remembering wave retains its shape: each of us is the ocean in this particular form. Each of us is Siddhartha come into a body: human siddharthas and piñon pine siddharthas and subatomic particle siddharthas.

Our human fate is to move the other way, right into the middle of our lives, and to remember there the salty taste, still in our mouths, of that vast ocean.

Human beings, especially ones involved in spiritual practice, often try to abandon the wave in favor of the ocean, as though there is something truer about the vastness of the ocean than about life as a wave. Zen teachers have colorful names, like corpse-watching demon, for people who succumb to this impulse. Our human fate is to move the other way, right into the middle of our lives, and to remember there the salty taste, still in our mouths, of that vast ocean.

This brings us back to how we feel about the dreamlike quality of life. If we believe that the ocean of essential nature is the true thing and that the world of our everyday experience is somehow less true, then the world becomes a veil that obscures our sight, an illusion we have to see through. But if we don’t create levels of reality and then rank them, if ocean and wave are aspects of one whole thing, then the dreamlike quality of life might become something that simply is, as far as we can tell. “Life often seems like a dream” becomes a wondering about how things are, rather than a verdict on them.

This world we are born into—this complicated, difficult, hauntingly touching world—is the one whole thing. It is the world we awaken in, and awaken to. Our awakening is made of this world, just as it is. It doesn’t come from some other realm like a bolt from the blue, and you don’t go to someplace else when you awaken. Awakening is not a destination, and meditation is not a bus ride. Awakening is the unfolding of an ability to see what has always been here. To see, more and more reliably, what is actually in front of you.

Neither the ocean’s perspective nor the wave’s perspective—sometimes called the absolute and the relative—is the whole truth; each is an aspect of the way things are. There’s an old story about a woman who’s been meditating very deeply, and she comes to that moment when everything falls away. Her young son arrives home from school, and she stares at him and asks, “Who are you?” We can understand the wonder of that question, asked from the perspective of everything fallen away. It’s not about whether she recognizes him—“Who are you?”—but, “Who are you? Who am I? Who is anybody?” And we can also see that this might be an alarming question for a seven-year-old boy to hear from his mother.

When we’ve experienced both the mother’s and the son’s perspectives, at first it’s a matter of holding them simultaneously. It’s as though, at any given moment, one is the foreground and the other the background, one up front and vivid and the other receding. Mostly, as we go about our everyday lives, what’s in the foreground is the realm of place and time, the world where we fall in love and eat peaches and have car accidents. Sometimes, in meditation or just walking down the street on a blustery day, all of that recedes, and for a while what’s in the foreground is how timeless and limitless and radiant the universe is.

As our meditation goes along, we might notice that these two perspectives begin to bleed into each other—foreground and background are no longer so distinct, and it isn’t a matter anymore of choosing between them. More and more the world begins to feel like one whole thing: one continuous ground, full of life, like white herons in the mist. Where do birds end and clouds begin? How is it that the black bamboo at my gate is eternal in the morning sun, and yet I remember planting it there more than a decade ago? The ageless bamboo planted in 1994—in its shade, the mother in the old story might think, “Oh, my radiant, completely empty son, it’s time for dinner; you must be hungry.”

There is a grace and a poignancy to experiencing life in this way. The dream of the world becomes a kind of field of awareness. We begin to experience things as rising and falling in that field, like herons stretching and slowly flapping their wings. A hungry child appears in the field. A dream of white elephants. A thought arises. A thought lasts awhile. A thought goes away. What we’ve experienced as a busy, insistent and separate self is becoming part of the field of awareness. Not a creature in the field, nor an observer of it, but the field itself, in which everything, even the parts of ourselves we are so familiar with, rise and fall as a dream.

What a relief it is when every passing thought or reaction doesn’t automatically take pride of place, doesn’t need us to bend the world according to its whim.

This can be a happy thing, when what rises in our hearts and minds seems no more and no less important than anything else in the field. A woman I used to know would say to her son, “The trouble with you is that you take your life too personally!” What a relief it is when every passing thought or reaction doesn’t automatically take pride of place, doesn’t need us to bend the world according to its whim.

The first passage from Siddhartha’s story ends when he is born and Mahamaya ascends to the heavens. The Great Dream is still mother to what happens, but the rest of the story is the working out of a particular human life. Part of this is coming to see the dreamlike qualities of life in the ways we’ve been discussing, and then taking another step: trusting the dream of life, because this trust is one of the things that helps make the world. Here’s how the story continues:

“Many years later, Siddhartha has been practicing such extreme austerities that he’s on the brink of death. Sitting in the forest, he faints with hunger. When he comes to, he is alone and disheartened, but suddenly he remembers something from his childhood: He is lying under a rose-apple tree, looking around. For the moment everyone has forgotten about him. He feels no resistance to what he sees, no sense that anything is lacking; there is nothing he wants other than exactly what is happening. He wonders why this image should appear now, and whether that early memory of ease, rather than the harsh discipline he’s been practicing, is the way to freedom. ‘Are you afraid of this happiness?’ he startles himself by asking. The answer is no, but he is too weak to do anything about it.

“Meantime, in a nearby town, a woman named Sujata falls asleep and has a dream. Because of the dream, she goes out to her family’s herd and milks a thousand cows, feeding their milk to five hundred cows, and so on down to the last few cows. She mixes this rich milk with rice, puts it in a golden bowl, and walks out into the forest. She has no idea what she’ll find, which turns out to be Siddhartha sitting under a tree, just awakened from his faint. Though he is weak, already there is a muted glow about him. She offers him her bowl of milk and rice, saying, ‘May this bring you as much joy to eat as it brought me to make.’ Siddhartha eats, and Sujata’s blessing flows over the harsh landscape of his austerities.”

Siddhartha and Sujata make this small moment in the vast sweep of the world by trusting the dreamlike quality of things. They take seriously the images that come to them out of that dream—Siddhartha’s in a memory of childhood, Sujata’s in her sleep. For each of them, a possibility appears from beyond the territory of what they already know, and they walk out to meet it. They share a willingness to take that walk without being certain that the path will be there under their feet. This is a fundamental kind of trust, and it has nothing to do with the likelihood that things will turn out as we think they should; though we know where the story is going, it might initially have seemed like a setback when Siddhartha’s small band of followers abandoned him in disgust because he took food from Sujata.

To trust the dream of life is to be at ease with the provisional nature of things.

A meditation practice that trusts in the dreamlike quality of life is like this. We meet whatever happens, come into relationship with it, and take another step. And we do this without the certainty that we are right—indeed, knowing that whatever we choose will in some way be a mistake. But we’re willing to take a step anyway, and to notice what happens, so that what we notice becomes part of the next step.

To trust the dream of life is to be at ease with the provisional nature of things. I’ve been me for half a century now, but that’s still provisional; it rose and will fall. How much more so our thoughts and opinions and moods, which come and go like the weather? And what are they compared to the Rocky Mountains, which themselves rise and fall, though much more slowly? And the Rockies compared to the Milky Way? When I sit on my deck on a summer evening, the Milky Way looks like an immense and timeless river of light across the sky, which consoles me in difficult times. But from closer up, it’s full of supernovae and black holes and red dwarves; things explode and collide, swirl in and out of existence, and everything is moving unimaginably fast. A Navajo storyteller might say that Coyote stole some bread baking on the coals of First Woman’s fire and left a trail of ashes across the sky. They’re all just different ways of interpreting the Milky Way dream, bits of the ongoing conversation that is human life.

We’re awfully lucky that life isn’t a monologue. There is so much that is unexpected and unplanned for, and those are the things that can make all the difference: raising a child you didn’t give birth to, helping an elderly neighbor as she’s dying, spending time in a foreign country because you fell in love with someone who lives there. Sometimes these things fall like grace from some unanticipated cloud, and sometimes it’s more like a meteor plowing into us. But the world is filled with stories of how hardships and difficulties can pull us deeper into life, if we let them; they can bring us heart and soul in a way the easy life never could.

In this dreamscape of a world, heavens and hell realms are a thought or a phone call or a news broadcast away. Children turn into adults you never could have imagined they carried inside them. The sky over the sea is full of pelicans, and then they almost disappear, and now the sky is full of them again, because humans started using DDT and then stopped. On any morning, what happens on the other side of the world can make you weep over your breakfast.

Perhaps, after all, we shouldn’t take our lives so personally, shouldn’t think of them as the monologue of busy and insistent and separate selves. Perhaps we are made up of landscapes and events and memories and genetics; of the touch of those we hold dear, our oldest fears, the art that moves us, and those sorrows on the other side of the world that make us weep at the breakfast table. The astronomer Carl Sagan used to say that if you really want to make an apple pie from scratch, you have to start with the Big Bang.

It’s as though there is a communal dreaming going on underneath everything, a great river of co-creation where our individual dreams, our individual lives, touch and are touched by the dreams of others, and that is how our common world is made. The world is full of meetings between Sujata and Siddhartha. I sat for years in a meditation hall among the redwoods on the California coast. I know that those trees became part of me, that my meditation has, among other things, a redwood flavor to it. And perhaps the redwoods made their own tissue of winter rain and summer light, and the samadhi of all those sitting in that hall.

When we’re not fighting with life, or turning away from it, joining in seems to come pretty naturally.

Needless to say, our co-creations aren’t always benign. We are equally capable of making nightmares like ethnic cleansing and impenetrable trances like fundamentalism. And there are the pinched daydreams of gossip and grudges and self-deception. When we run into this recalcitrant stuff, we sometimes fall back on distortions of the ocean and wave perspectives: either nothing matters because it’s all empty, or everything is a mess, and that’s all that matters. But if we can rest in the dreamlike quality of life, if we find it moving rather than problematic, then the natural view is something like, “Oh, my radiant, completely empty son, it’s time for dinner; you must be hungry.” By which I mean, to experience the dreamlike quality of life is to understand that there is something mysterious at the heart of things, something we can’t figure out or get control of. It’s a mighty big ocean whose surface we skim. If we lean back into that experience, we’re more and more at peace with what isn’t certain, and less and less in a chronic state of complaint at what W.H. Auden called the disobedience of the daydream. We spend so much time disappointed in life for being life. But as we feel less and less resistance to things as they are, as peace grows in the midst of uncertainty, kindness is not far behind. We’re not at war with life so much anymore, and that is a kinder way to be. When we’re not fighting with life, or turning away from it, joining in seems to come pretty naturally. Someone is hungry; it’s time to make dinner. An election turns out badly; where do we go from here? When we’re aware of the dream of life, we know that we’re part of its co-creation whether we act or not.

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily,

Life is but a dream.

The word “merry” came from roots meaning “pleasing” and “of short duration.” This poignant life, so fleeting and yet made entirely of eternal moments—this is the dream we are making together, this is the dream that is making us, and that is the one whole thing.