In my earliest days of running, when I was chosen for my elementary school’s relay team, I was guided by our coach—a haunted-looking history and gym teacher with small, sad eyes like brown marbles. He always smelled strongly of nicotine, a crumpled pack of Pall Malls visible through the pocket of his dress shirt. My dad, a successful high school track coach who had led his teams to district and state championships, also insisted on tirelessly working with me in our backyard, honing the finer points of my starting stance and baton hand-off technique.

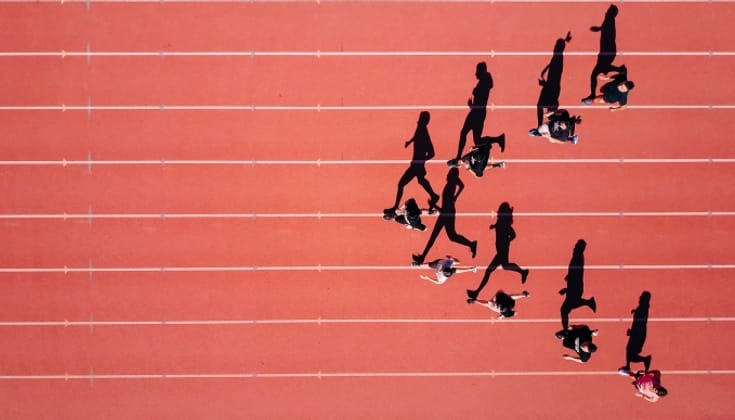

Both men were patient, detailed, and exacting. I was not. They shared a certainty of a right way to start, charging out of the starting blocks at just the right low angle and propelling your body forward in a sort of explosion. There was a perfect time and procedure to transform your body out of that explosion, to rise from that sharp, low starting angle and begin lifting your legs and putting them down as fast as you could. There was a proper way to hold the head and body as you ran, the arms pumping neither too hard nor hanging too loosely, the hands not flopping but the fists not clenched too tightly. And there was a right method to hold the relay baton at the start, and an exact right time to hand it off, and a precise point in space to place the baton firmly, but not too firmly, in the next runner’s outstretched hand.

All of these movements involved dozens of well-defined details, many lasting only a second or so. Each of those details was deeply, critically important, and the success of one depended on the correct execution of all of the others. But the correct start was absolutely necessary. For my coach and my dad, how you started determined where your entire team finished. The quality of the start, to them, was everything.

As I endured them gently but firmly grabbing my shoulders and carefully aligning them with the rest of my body for what seemed the millionth time, I could never get past believing that starting only meant I wasn’t fast enough to be picked to finish. Like so many other things in my boiling restless young life, I just wanted to get past the starting line and get to wherever I was going as fast as I could. But my coach and my father were both quiet, determined men focused on a single purpose, and that single purpose could only be approached two ways: correctly, or incorrectly.

I listened to them as best I could, and all I remember from the race is rounding the first turn and handing off to my teammate who was running the second leg, his eyes widening as he stretched to grab the baton from my hand, just as we had been coached. I let go my grip at the right moment and slowed to a stop, the cinder crunching under my feet as I gasped for breath and the pack scampered away from me, leaving me in a spray of gravel dust and increasing quiet. The crowd in the stands by the finish line on the other side of the track sounded a hundred miles away, and I strained my eyes to barely make out our team’s anchor darting first across the finish.

In a few frantic breaths, our weeks of preparation were over and our job was done. Back at school, our coach would nod at me and the rest of my teammates in the halls, but he was never one for a lot of friendly chatter, and I found out being on his winning relay team didn’t really change that. We pinned our blue ribbons to our shirts and wore them to school for a few days, but they quickly began fraying and fading, and our friends soon stopped asking about them. My dad was proud of me, and I greedily drank in that pride. But he was already pressing for new starting lines, new ways for me to grow up a little more.

My dad and my coach are no longer alive, but they are still with me: the way I loosely hold my fists as I run, with only my thumb and forefinger lightly touching in a sort of runner’s mudra, comes from their constant admonition to relax. And as I feel my thumb and forefinger lightly rub against each other, I realize my focus on body awareness and relieving physical tension also comes from my Zen teachers. “Whenever I lose focus, I always find my way back by checking on my body first,” one of my teachers told me, and it is her words, and the words and actions of my dad and track coach, that intertwine and coalesce across the decades, across practices and disciplines, across backgrounds and cultures, to cross fertilize my running and my zazen.

My early approach to meditation was influenced by my increasing awareness that it was also a physical practice, and my running training schedules—modified from examples provided by widely-published exercise and running gurus—provided the inspiration for how I trained myself for Zen. I slowly increased my sitting time from five minutes to just over thirty, as I followed their examples of slowly increasing the pace and intensity of shorter runs before attempting longer races. I considered my first weekend sesshin as my first marathon and my first week-long sesshin as my first ultramarathon, and “trained” for both accordingly. Yoga also became important to me during prolonged sesshins, helping to relieve the pain and stiffness from prolonged periods of sitting and so yoga teachers, through their books and online websites, unknowingly became part of my growing crowd of mentors. It wasn’t long before I realized yoga would be an effective lower-impact approach to the strength training I did for running, and so yoga came to influence my running as well, and my Zen. Circles within circles, widening and even erasing their own boundaries… a Zen lesson in itself, an ever-expanding circle of awareness and influence.

“Your father is still your father,” another of my Zen teachers told me, not long after I had attended my dad’s memorial service, and each time I run, I still feel the patient but firm grip of my dad’s hand on my shoulder as he smoothed out my starting stance. I hear my Zen teacher telling me to run with mu, and I run and sit with my father, my Zen teachers, world-renowned Buddhist teachers and running coaches I have only read, family, friends, fellow runners on the path and sangha members in the meditation hall—their experience a part of me and a part of each other, wise words, firm hands and patient teaching living on, however inexpertly, in a huffing, puffing middle-aged man trudging up a hill or bringing himself back, for the millionth time, to himself as he squirms slightly on his cushion. One sentient being, always with many others. May they never tire of guiding me, although I certainly know I’m not an easy pupil.

Fortunately for me, my teachers are often not even aware they are teachers. On the last morning of a weekend sesshin I attended, I drove up to the zendo a few minutes ahead of time to find the entrance gate closed.

Irritated, I pulled my car off the road and parked across the street, staring at the gate. Why is the gate locked? I wondered. It wasn’t locked yesterday. Am I late? Did I read the schedule wrong? Why hadn’t someone been told to go unlock the gate? Wasn’t anyone thinking about the commuters? Why are things so disorganized? I’m going to be late. Being late is so embarrassing. Why does stuff like this always happen to me? Why can’t I keep things straight?

Another sesshin participant drove up. She stopped her car, got out, gently pushed the unlocked gate open, and drove inside.