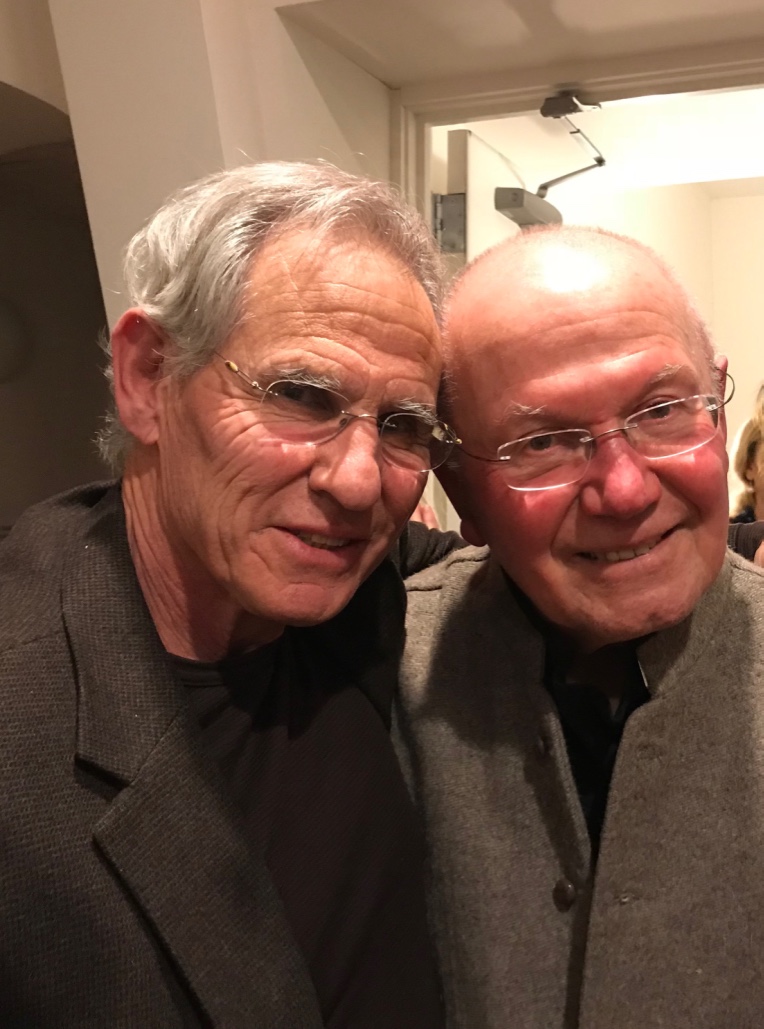

Larry Rosenberg and Jon Kabat-Zinn met in the mid-1960s and have been best friends ever since. When Rosenberg set out on his quest, Kabat-Zinn was his only source of emotional support — finding places for him to live, storing his belongings, helping out with moving, even delivering his wife’s chicken soup when Rosenberg came down with the flu. “We’re true dharma brothers,” Kabat-Zinn said. Or as Rosenberg put it, “We’ve been the two supports of each other in an ocean of doubt.” Not long after Rosenberg left academia for points unknown, Kabat-Zinn, a longtime teacher of meditation and hatha yoga by that point, began mulling the foundation of what would become mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), which has been adopted globally in a vast range of applications, from the corporate world to education to the armed forces. Like Rosenberg, Kabat-Zinn also faced ridicule — in his case, for apparently throwing away a PhD in molecular biology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he worked in the laboratory of a Nobel laureate. Fittingly, Rosenberg and Kabat-Zinn were in adjacent rooms at a meditation retreat in 1979 when Kabat-Zinn hatched the revolutionary idea of MBSR. “Who else could I talk about it with but Larry?”

Outwardly the two men were opposites. While Rosenberg was a convivial hermit, solid and earthbound, with a low center of gravity, Kabat-Zinn, twelve years younger, was outgoing and effusive, lean and kinetic. While Rosenberg became a vagabond for many years, Kabat-Zinn chose the Buddhist “householder” route — marrying, having children, holding a regular job. “Our paths took very different directions, but beneath all appearances, they’re exactly the same,” Kabat-Zinn said. “We were always looking for ways to live our lives committed to embodied wakefulness and wisdom.” He sometimes referred to Rosenberg as his “windshield” because Rosenberg was often the first to make contact and check out Asian teachers passing through the spiritual bazaar of Cambridge, giving Kabat-Zinn the green light only if the itinerant masters were up to snuff. Unlike today, when a book search on Amazon for “Buddhism” turns up tens of thousands of results, dharma literature back then was scarce; the two friends spent hours scouring underground bookstores specializing in esoterica of all sorts. Among other things, Rosenberg came across a series of thin pamphlets called The Wheel, published in Sri Lanka, written by practicing monastics, and chock-full of what felt like dharma gold.

Fittingly, Rosenberg and Kabat-Zinn were in adjacent rooms at a meditation retreat in 1979 when Kabat-Zinn hatched the revolutionary idea of MBSR. “Who else could I talk about it with but Larry?”

For a time in the early 1970s, they led classes together on Tuesday nights at various churches around Harvard Square — Rosenberg teaching meditation, and Kabat-Zinn, yoga. (During one, while Rosenberg and his students were deep in meditation, a thief sneaked in and stole wallets and purses that the yogis had casually piled on a stage.) After teaching, the dharma bros went out to dinner and talked for hours. “It was like we were in love. Two minds, two hearts, delighting in inquiry, sharing, humor — a lot of humor,” Kabat-Zinn recalled. “Most people, understandably, come to the dharma because they are hurting, often badly. They are seeking relief. They want healing. They want transformation. Larry and I came to the dharma mostly out of wonder, out of love, out of a sense of exploration and inquiry into the nature of reality beyond the conventional explorations within the academy. We were deep into the koans, Who am I? and What am I?”

I asked Kabat-Zinn how the two maintained such an intense friendship for so long: “I listened to him. He listened to me. It’s very easy to talk, but to be heard — that is a whole different story. When you feel met and heard, and you’re talking about only the most important thing in the universe — your love for dharma and what you’re going to do with your life, which is the only thing we ever really talked about — you only need one friend like that. You’re way ahead of the curve to have even one friend with whom you can connect around a common love of practice and have a conversation like that every week.” To this day, on the less frequent occasions when they can meet in person, they rarely reminisce, preferring to have lunch, drink matcha tea, and share the increasingly precious moments together that they have left.

From The World Exists to Set Us Free © 2025 by Larry Rosenberg with Madeline Drexler. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com.