He’s a big name now, having written such classic stories as Watchmen and V for Vendetta. And his new 1300-page book, Jerusalem, promises to be an event. But in 1984, while still a relatively unknown writer, Alan Moore began scripting the DC scifi/horror title, Swamp Thing. During his run, Moore took the Swamp Thing’s boilerplate origin story — a lab explosion throws plant scientist Alec Holland into a swamp, where the toxic chemicals in the mud transform him into the titular vegetative monster —and retconned it. The new story resonated strongly with a Buddhist understanding of selfhood and the nature of reality.

The Swamp Thing and the Skandhas

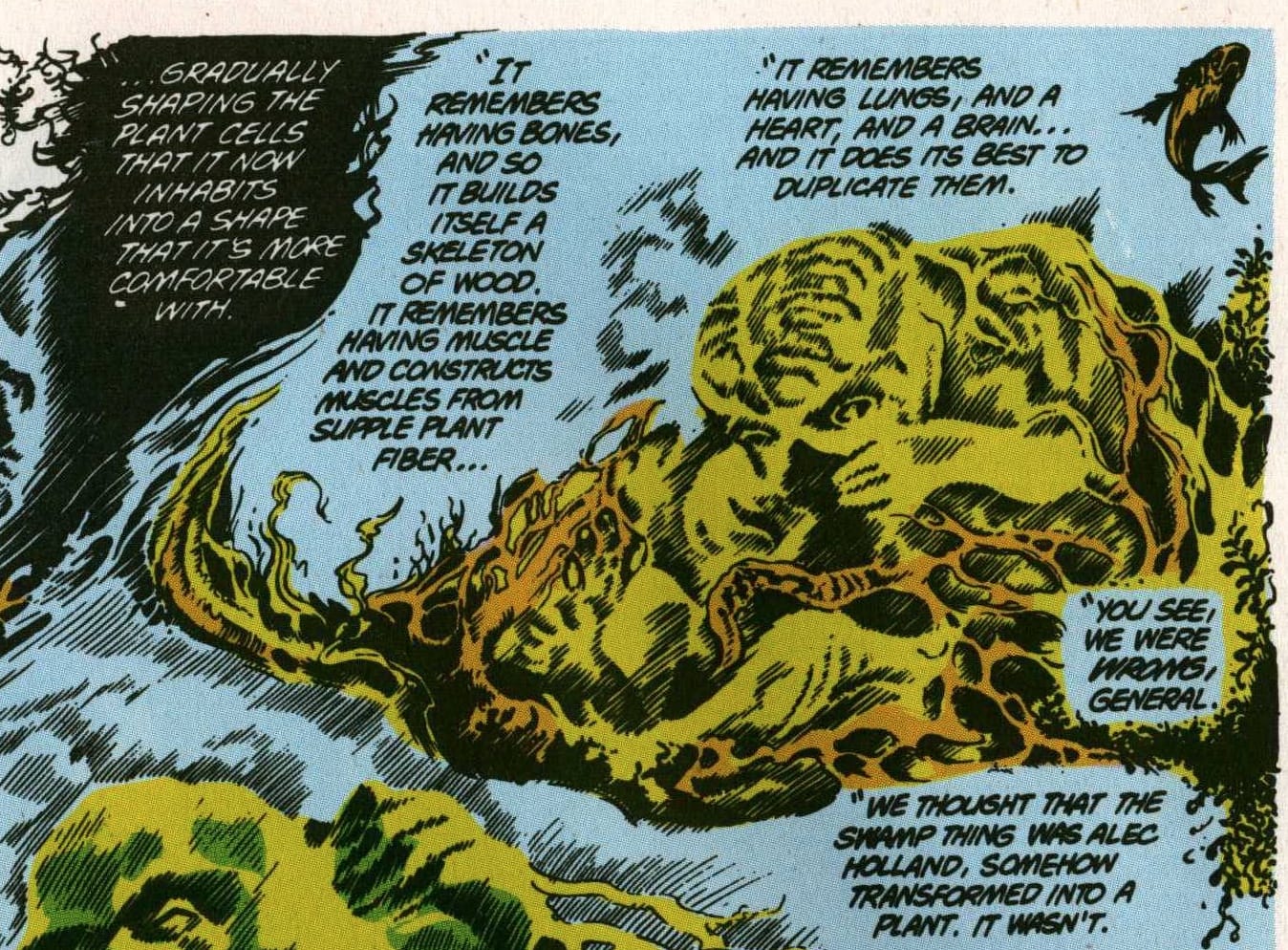

Swamp Thing’s creators depicted the character as a transformed version of Alec Holland. In Moore’s version of events, though, Holland died in the original lab explosion – the Swamp Thing formed only after the chemically-enhanced plants surrounding his body absorbed his memories and, believing themselves to be Holland, took the shape of a man. The Swamp Thing’s sense of itself as a permanent entity called “Alec Holland” is therefore an illusion — he is not the soul of a man trapped in a vegetable body, but rather an aggregate consciousness with no real connection to the dead scientist.

This recalls the tale of Nagasena’s chariot, as described in the Pali text The Questions of King Milinda. In the story, the Buddhist sage Nagasena explains the Buddhist doctrine of “no-self” by demonstrating that the king’s chariot exists only as an accumulation of its component parts — wheels, axles, etc. — and has no inherent existence of its own. Moore’s Swamp Thing, too, lacks any permanent self, atman, or “soul” by the name of Alec Holland. He is an accumulation of smaller components, namely the plants which have grown together to approximate Holland’s human form.

In a storyline involving the Swamp Thing’s escape from the Sunderland Corporation (Holland’s employer at the time of the accident), the monster uncovers the true nature of his existence and goes temporarily insane, killing Sunderland’s CEO in a violent rampage and descending into hallucination. In the next issue, Moore shows how the Swamp Thing first formed its sense of “self.” The process neatly parallels the interaction of Buddhism’s five skandhas, or aggregates, the building blocks of self: form, sensation, perception, mental formations or thoughts, and consciousness.

In The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation, Chögyam Trungpa explained that the first skandha, form, arises when “we are bewildered by the discovery of selflessness and do not want to accept it.” Like Trungpa’s “bewildered” hypothetical subject, Moore’s budding Swamp Thing tries to deny its own selflessness; the fragments of Holland’s memory, embedded in the swamp, shore up their notion of selfhood by growing a human form.

Trungpa explains the second skandha, feeling, by saying, “One must constantly try to prove that one does exist by feeling one’s projections as a solid.” Moore makes this solidification of the Swamp Thing’s “projections” into a literal process of material growth: to ground the projection that is Alec Holland, the plants create a “solid” body, with which to feel.

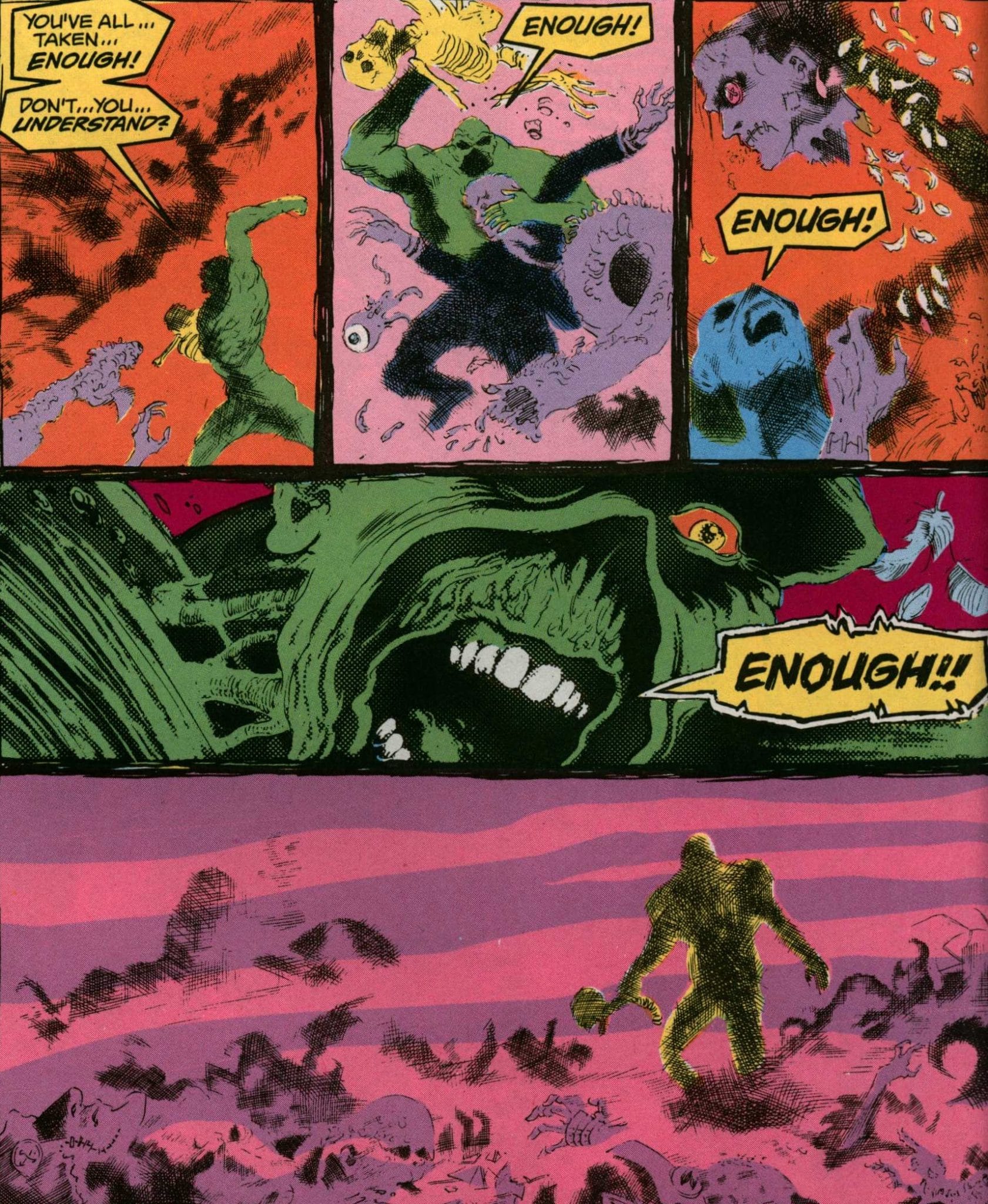

According to Trungpa, “In the third stage, ego develops three strategies or impulses with which to relate to its projections: indifference, passion, and aggression,” the last of which he characterizes as “the feeling that you cannot survive and therefore must ward off anything that threatens your property or food.” Traumatized by the knowledge of his true nature, the Swamp Thing falls into a vivid hallucination, in which his struggle to come to grips with his identity is dramatized as an ongoing battle with demonic entities who wish to steal his “humanity.” This humanity, his false notion of self, takes the shape of a symbolic skeleton, grasped tightly to his chest. When his pursuers demand his humanity, he flies into a rage, “warding off” the attackers. He is “relating” to the illusory projection of his humanity as we all do — by alternately trying to maintain a hold on it and attacking anything that threatens it.

“’Intellect’ or ‘concept’ is the next stage of ego, the fourth skandha,” Trungpa tells us. “Since we have so many things happening, we begin to categorize them, putting them into certain pigeon-holes, naming them.” Sure enough, the Swamp Thing’s propensity for “naming” goes on full display when his humanity is threatened. Holding the skeleton tight, he shouts that “It’s my humanity […] It’s mine!!” In vain, he seeks to make his ownership of the thing an irrefutable fact, to make reality out of an illusion.

Lastly, Trungpa explains that the fifth skandha, consciousness, “consists of emotions and irregular thought patterns, all of which taken together form the different fantasy worlds with which we occupy ourselves.” Moore draws on his conceit about as far as it will go — the consciousness known as the Swamp Thing creates an entire hallucinatory hell for himself, a fantasy world where he can grapple with snarling demons rather than face up to the potentially more terrifying truth of his impermanent existence.

The Swamp Thing Sits Zazen

In Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Shunryu Suzuki claimed that “the best way to relieve your mental suffering is to sit in zazen,” and that “When you take this posture [sitting], you have the right state of mind” — the mind of enlightenment. In the Swamp Thing’s struggle with his humanity, Moore provides an allegory for just such a meditative process.

The Swamp Thing’s pet skeleton, now reduced to a skull by the fighting, begins to annoy him with its constant chattering. He sits on a nearby log, lets go of the skull, and ignores it’s yakking. Doing so brings him a sense of mental peace.

Moore uses his graphic medium to reinforce the link between sitting and the relief of “mental suffering”: the Swamp Thing sits and, in the same panel, realizes that there is no point to hauling around his painful illusion. In other words, Moore presents the realization and the sitting as occurring in the same moment – the Swamp Thing comprehends the truth of his situation “when he takes this posture,” and not a moment before or after. As long as he runs and fights, he is caught up in his “mental suffering.” He eases that suffering by taking a moment to sit, allowing the projection which fuels his anguish to grow silent and insignificant.

The Swamp Thing Attains Nirvana

As he sits, the Swamp Thing begins to dissolve back into the swamp from which he came. The process parallels the experience of enlightenment, i.e. the meditator’s transition from the realm of samsara — which Trungpa defines as “the continuous vicious cycle of confirmation of existence”—to that of nirvana, or release from samsaric existence. The Swamp Thing escapes this “cycle” when, through sitting, he is finally able to let go of his humanity/ego. He merges with the larger swamp, tapping into a massive vegetable neural network which connects plant life around the world. Growing back into the swamp which spawned him, tangling his roots with those of the trees, he literally becomes an undifferentiated part of a larger whole. His suffering ends. His return to the swamp calls to mind Suzuki’s metaphor of the water droplet’s return to the river — both droplet and Swamp Thing are dissolved in the flow, no longer struggling to maintain an ephemeral self.

All of which takes place in just a brief retcon. In subsequent issues of Swamp Thing, Moore would go on to wrestle with such complex Buddhist subjects as the nature of death, reincarnation, and even the function of the chakras, to name just a few. (It’s perhaps worth noting that, all these years later, he describes Jerusalem as filling the need of providing “alternative way of looking at life and death.”) A self-professed and proud autodidact, Moore not only demonstrates knowledge of Buddhist thought, but also skillfully weaves that understanding into the larger fantastical web that is the story of the Swamp Thing. With wisdom and a striking attention to detail, Moore crafts a work of art in which a Buddhist can’t help but find profound meaning.