Like many, I’ve experienced the past months as an unrelenting, reckless assault—not only on people, especially the most vulnerable among us: immigrants, the poor, the disabled, LGBTQIA+ individuals, BIPOC communities, women, children, veterans, students, and the elderly—but also on the very fabric of our shared life. It’s understandable to feel helpless, powerless, and scared at the immensity and speed of the destruction. I feel scared, too.

The intention of the barrage of devastation is to immobilize us and convince us that resistance is futile. But as Timothy Snyder writes in On Tyranny, it’s when people keep their heads down and “obey in advance” that authoritarian regimes succeed. How can we practice and apply the dharma so that we can claim our own power in this moment and take meaningful action? What Buddhist wisdom can inspire us?

The first stanza of “Experience,” a poem by the late Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, offers powerful motivation. It expresses and reflects on the extreme suffering he and other social workers witnessed during a trip up the Thu Bon river in 1964 when they were taking food to those devastated by flooding:

I have come to be with you,

To weep with you

For our ravaged land

And broken lives.

We are left with only grief and pain,

But take my hands

And hold them, hold them.

I want to say

Only simple words

Have courage. We must have courage,

If only for the children

If only for tomorrow.

Don’t Obey in Advance

The Buddha also lived through times of great instability, war, injustice, and division. He remained anchored in his practice of mindfulness and compassion, continuing to teach the dharma and offer a presence of love, even when his sangha of monks split into two deeply polarized camps, and even when he was physically attacked in an assassination attempt plotted by his disciple Devadatta and a prince named Ajatasattu. The Buddha never felt any ill-will toward them and constantly included them in loving-kindness. He kept practicing mindfulness in every moment, and eventually his love overcame their hate. They repented, and he welcomed them back into the sangha. His teachings can inspire us to stay steady in this moment of great upheaval, restore ourselves, and take wise, compassionate action. He’s a model for us all as we seek to take care of each other and ourselves.

Tending to this very moment is so important, for the future is made only of this moment. When we feel powerless and helpless, we can come home to ourselves and connect with our breath and body. In his last teaching before he passed away, the Buddha encouraged his disciples to cultivate the “island within.” That is, we shouldn’t take refuge in any other person or thing, but only in the energy of awakening that each of us has inside. We can each do this now. Only by tending to reality, moment by moment, can we access our inner power. We may be tempted to give up our inner power when feeling helpless in the face of external power, but this would be a kind of obeying in advance. Don’t do it!

Practice “Sacred Criticism”

If we want a different kind of world in the future, we’ll have to be the seeds of that world now. As the late activist A. J. Muste said, “There is no way to peace; peace is the way.” We cannot sacrifice the means for the ends. Other people are not our enemies, no matter what they believe or do. It’s discrimination, ignorance, and violence that we oppose, and we must stand up against these harmful attitudes, in whomever they manifest, including ourselves.

It’s possible to call out the harm that’s happening right now without despising or hating those enacting and supporting it. As it says in the Eight Realizations of Great Beings Sutra:

Bodhisattvas practice generosity,

beholding the friendly and hostile equally.

They neither harbor grudges,

nor despise malicious people.

We can engage in what Richard Rohr calls “sacred criticism,” where we challenge injustice and hatred with love in our hearts, knowing our interconnectedness with all living beings and the ways we’re all held in love. An example of sacred criticism can be found in 1963, during the war in Vietnam.

The Ngo Dinh Diem dictatorship was violently suppressing Buddhism, even forbidding the celebration of Vesak, the Buddha’s birthday, and attempting to mass-convert people to Catholicism. There was a massive Buddhist uprising, with months of protests led by monks, nuns, and then students when the monastics were jailed. A number of Buddhists self-immolated to draw attention to the gravity of the injustice and suffering, and thousands were arrested, tortured, and killed.

In Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War, Sister Chan Khong writes how the National Buddhist Congregation wrote an open letter and petition to the Diem government. Thay Tinh Khiet, the High Patriarch, added to it Buddhist principles, which included this one: “Buddhists vow to follow a nonviolent path, practicing the teachings of the Awakened One during the struggle itself. Because of our commitment to nonviolence, we Buddhists are ready to sacrifice ourselves in the spirit of understanding and love. We want more than just a change of policy. We want the spirit of love and understanding to inspire and transform the hearts and minds of people, including those in government.”

What would it mean for us now to work not just for a change in policy, but for love and understanding to inspire transformation at the deepest level?

These past few months, I’ve appreciated engaging with the work of Braver Angels (BA), an organization focused on bridging political divides. BA hosts workshops, debates, and events that bring together conservatives (“reds”) and liberals (“blues”) to foster mutual understanding and identify common ground. Their training emphasizes tools that can help people see themselves in others with different views. I found it refreshing to participate in a workshop on “depolarizing within,” where I learned how I was contributing to political polarization in my ways of thinking and speaking and how I could resist this. I also enjoyed attending a recent “fishbowl” session for two groups of “reds,” one being conservatives who support Trump’s policies and the other being conservatives who do not. It was helpful to see the differences among them and reassuring to find out that most folks, in both groups, were concerned about the current administration’s actions in light of the health of the constitution and the rule of law. I noticed how often we tend to lump everyone on the opposite end of the political spectrum into a single category, even though their views may be more nuanced.

True inclusivity means even loving those who hate us, so that the greatest possibility for transformation can arise. “Somehow we must be able to stand up before our most bitter opponents and say: ‘We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering,’” said Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “‘We will meet your physical force with soul force.…We will not only win our freedom for ourselves; we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.’”

Double victory is only possible when we stay connected to ourselves and our own goodness. We’re more than just this moment in time, more than this finite human life.

When we get caught up in the day’s news cycle and find ourselves drowning in the bad news jumping out from screens and feeds, we need to remember that there are two dimensions in Buddhist ontology. There’s the historical or relative dimension, which is the one we mostly relate to, with its observable phenomena, its pairs of opposites like birth and death, up and down, before and after, here and there, coming and going. This is the realm of Newtonian physics.

But then there’s the ultimate dimension, an infinite realm, beyond birth and death and up and down. This is more like quantum physics, in which the rules of the historical dimension do not apply. Imagine that you’re the ocean. On the surface, there may be a great turmoil of crashing waves. This is the relative reality of water. But remember that you also contain the still, quiet depths. Accessing the ultimate dimension is critical to engaging skillfully in the historical dimension.

We can call on our ancestors, who exist in the ultimate dimension, whether they be people of our family line, our spiritual lineages, or our lands of origin. We can access power and support from our ancestors by reflecting on the many dangers and disasters they survived and how they’ve passed their strength and wisdom on to us. One wonderful practice in these times is to identify an ancestor whom you admire, who lived in a noble, courageous way. Learn about their life and reflect on it often, bringing their wisdom into your daily life and maintaining dialogue with them in the midst of challenges. How would they approach this difficult moment? What kind of support can you draw from them right now?

Anchoring in the Good

I recently learned how to darn socks and other wool clothing that has worn so thin that there’s a hole. You take thread and anchor it in the good, whole part of the cloth on the bottom and then cross it over the hole to anchor again in the solid fabric on the top. First, you sew back and forth vertically, and then you work horizontally, weaving each thread over and under the vertical threads until you’ve basically woven a patch.

Well, the fabric of our nation has worn thin, and in some places, it’s worn out. How can we repair the threadbare holes that authoritarianism is creating? How do we anchor in the good, solid, beautiful aspects of our culture and in what is honorable and deserves protecting in our country’s history and peoples? And how do we do this over and over until new cultural traditions and ways of living together arise to replace and repair what’s being destroyed?

When I look back to see what’s good in our country, I recall the genius of George Washington Carver, who was born into slavery and yet became a brilliant scientist, educator, and humanitarian. Guided by deep religious faith and love for others, he revolutionized agricultural science and helped improve the quality of life for impoverished farmers. After successfully developing hundreds of plant-based products, Carver received an invitation from Thomas Edison to work with him in New Jersey. Edison offered Carver a salary that would be worth nearly one million dollars per year today. However, Carver declined, choosing instead to stay at Tuskegee to support Southern farmers.

I also anchor in the good in our country when I reflect on the Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps, and the thousands of servicewomen and men who supported them. They were the first African American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces, overcoming racial segregation and discrimination—both within and outside the military—to serve with distinction during World War II. Their exceptional performance directly influenced President Harry S. Truman’s decision to desegregate the U.S. military. Their legacy became a powerful symbol of African American resilience and excellence, inspiring the broader civil rights movement.

These reflections are anchoring in the intact cloth of our nation. All of us can reflect on what’s good about democracy and the rule of law to inspire ourselves and others to lift up and keep alive what we want to preserve in our culture and history.

On a day in 1965 that’s known as “Bloody Sunday,” young and old marched for civil rights in Selma, Alabama. When they attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were brutally beaten and tear-gassed. Flossie Menifee, now in her eighties, marched as a high schooler. As she said in an interview, it was a day she’ll never forget.

I was in the front of the line and I got a lot of tear gas, and I had to go to the hospital that day.… My cousin was an orderly at the hospital that morning. He came down and he found me lying in the hallway. He went and got my sister-in-law.… She said, “You don’t have any insurance, so you really shouldn’t be here. Your mom doesn’t have any money to pay for this. So, we’re gonna take care of this and nobody will ever know you been here.” She gave me a basin, and she gave me some chalk to drink. She said, “I want you to throw it up until this tear gas is out of you.” When I was done, a guy came and took me back to the church where we originally started out. I went home and that night [came back for a] mass meeting. My mom didn’t want me to march anymore, but it was too late. I was hooked.

Menifee’s high school threatened to expel her for her activism and not let her graduate, but so many students joined the march that they couldn’t expel them all, so they ended up letting them graduate. It was the same with the teachers in her high school. One was threatened with firing, but so many teachers were won over by their students’ determination to achieve equality that they too joined the demonstrations. The school didn’t fire anyone, because it would have been too disruptive to fire them all.

As Menifee’s example shows, if we resist together, we can accomplish much. This is a moment to engage, not to keep our heads down and go with the flow, but to build community and engage locally.

Authoritarianism is about oppression and control from the top down. Claiming and strengthening our horizontal power—in which everyone has a say in the decisions affecting the collective, and everyone is valued and respected—is needed now.

My dad marched on Bloody Sunday sixty years ago. Just as we can anchor our nation-darning in the goodness, courage, and brilliance of the Black Americans mentioned above, I also want to anchor in the goodness and integrity of white Southerners, like my dad, who stood up for civil rights. Amid the harsh segregation and racial violence that plagued Alabama’s Black community in the 1960s, my dad was part of the field staff for a Southern Christian Leadership Conference, so he helped organize and mobilize white Southerners sympathetic to civil rights. He along with others catalyzed the formation of The Concerned White Citizens of Alabama, which advocated for racial equality. They joined marches in support of African American voting, and as a result they often lost their jobs and were violently harassed and threatened.

I want to anchor us in the good by sharing the incredible legacy of Winston County, Alabama, which stood out during the U.S. Civil War as the only Alabama county not to secede from the Union. Winston County also generated one of America’s most profound leaders for justice, the white Southerner Judge Frank M. Johnson (1918–1999). In his thirty-seven-year career he ordered the desegregation of public schools and colleges and all manner of public places, as well as the Alabama State Police. It was also Johnson who, in 1965, made the decision to allow King and others to complete their march from Selma to Montgomery two weeks after Bloody Sunday.

Judge Johnson faced ostracism, cross-burnings, and death threats for his groundbreaking civil rights rulings, yet his decisions played a crucial role in transforming the segregationist South during the 1950s and 1960s. He and Winston County, Alabama, are part of the fabric of this country that we can anchor in.

As with Winston County and Judge Johnson, we need to know our full history, not just the legacy of racism and colonialism. The modern book bannings that seek to erase our country’s history in order to preserve white comfort and protect white children from feeling guilty about the past wouldn’t be necessary if we knew how to anchor in the good and lift up the many people and communities, of all races, that have fought for equality, integrity, and justice. Instead of wiping out painful aspects of our history so that we can avoid confronting inequality along racial, gender, and other lines, we could instead celebrate the ways our country has turned toward its shadow and tried to address it. There’s much to be proud of as well as to atone for.

This is a time to learn all we can about democracy. Education in civics in public schools has been on the decline since the 1960s, and an uneducated population is more easily manipulated and controlled. We can learn from the stories of people who grew up under authoritarianism and from the countries that have come back from it. As Richard Heinberg said, “Most of human history has been lived under authoritarian rule. If that’s not a future you aspire to, action is required.”

Celebrate Resistance

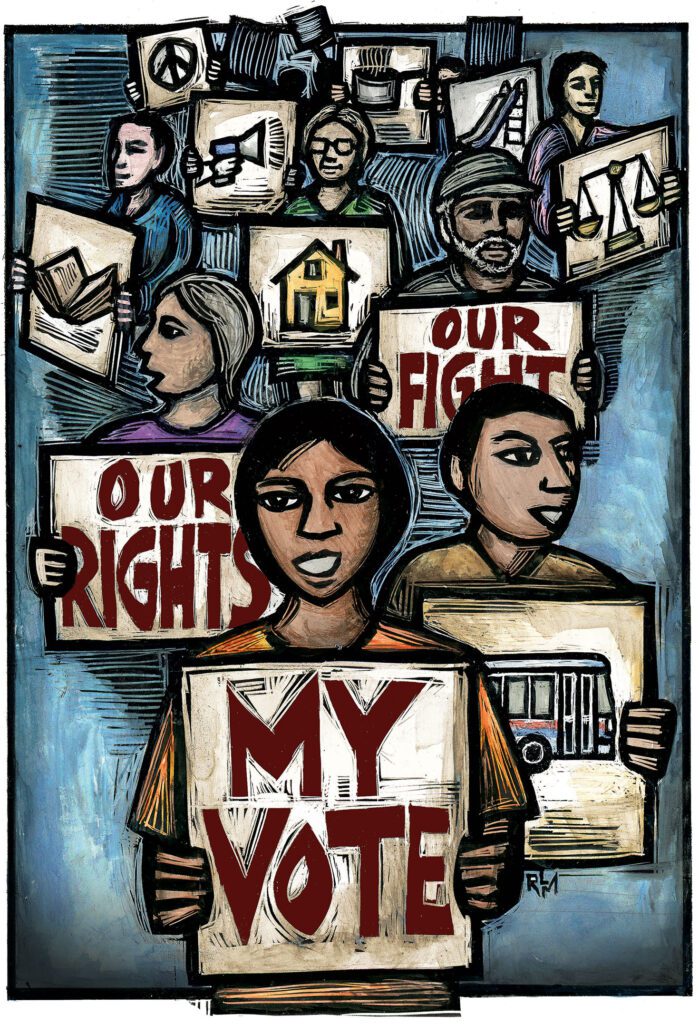

While we might want to focus on the negative things that are happening to us, we can also appreciate how much people are standing up for right now. Resistance is alive and effective. Across the country, people are speaking out and pushing back against policies that threaten democracy, justice, and human dignity.

The Tibetan practice of rejoicing in the good deeds of others can inspire us to recognize, join, and amplify courageous action. As Rivera Sun documented for Waging Nonviolence, opposition to harmful policies has taken many forms. In early 2025, over 25 percent of U.S. consumers dropped brands over political issues, largely in support of DEI and social justice. People are being encouraged to shop at stores like Costco and Aldi’s, which have made public declarations that they will uphold DEI policies.

A growing number of schools and districts have refused to back down on transgender policies, reaffirming their commitment to some of their most vulnerable students. Alaska’s legislature rejected Trump’s attempt to rename Denali, and governors in Michigan, Massachusetts, Maine, and Delaware are holding firm on LGBTQ+ protections, DEI, and immigrant rights—despite federal pressure.

Fear has turned into action, and action into tangible wins. The resistance has repeatedly mobilized tens of thousands, disrupted unjust policies, and inflicted economic consequences on those fueling oppression.

We can celebrate this momentum. We can lift it up and let it inspire us to also get involved. There’s the recent Buddhist Coalition for Democracy’s Call to Action and Statement of Principles that you could read and sign if you’re moved, perhaps sharing it with your community. There are numerous Buddhist organizations and groups who offer teachings, practices, and ways to take action, like the One Earth Sangha, Earth Holder Sangha, ARISE Sangha, Sacred Mountain Sangha, and the Zen Peacemaker Order. We can make resistance joyful: bringing our own creative and innovative ideas, with art, music, and community gatherings to sustain and amplify the message of love and understanding, anchored in a vision of a government for the people, of the people, and by the people.

This is a time to harness our inner power. We may feel powerless in the face of brutal and cruel external forces, but we have great power that we can cultivate inside ourselves and within our communities. If we allow hate and despair to take us over, we’ll find our internal power depleted.

One sustainable and helpful action is to regularly gather with a group of friends to share a meal, share the challenges and joys in your lives, and decide how you want to exercise your collective energy. Reflect on what particular form of resistance or action appeals to you as a group, and know you can call upon each other when an action needs to be taken.

We can each find our own creative and unique ways to resist. Let us focus on what we can do in our own lives rather than lose ourselves in what we cannot control, which can be paralyzing. If we stay connected to our own body and mind, we can bring our best to bear right in our own community to support health, connection, justice, and the enduring capacity to resist. Let’s stay connected to joy, and to each other, so that we can together summon the courage needed in this moment and in our shared future.