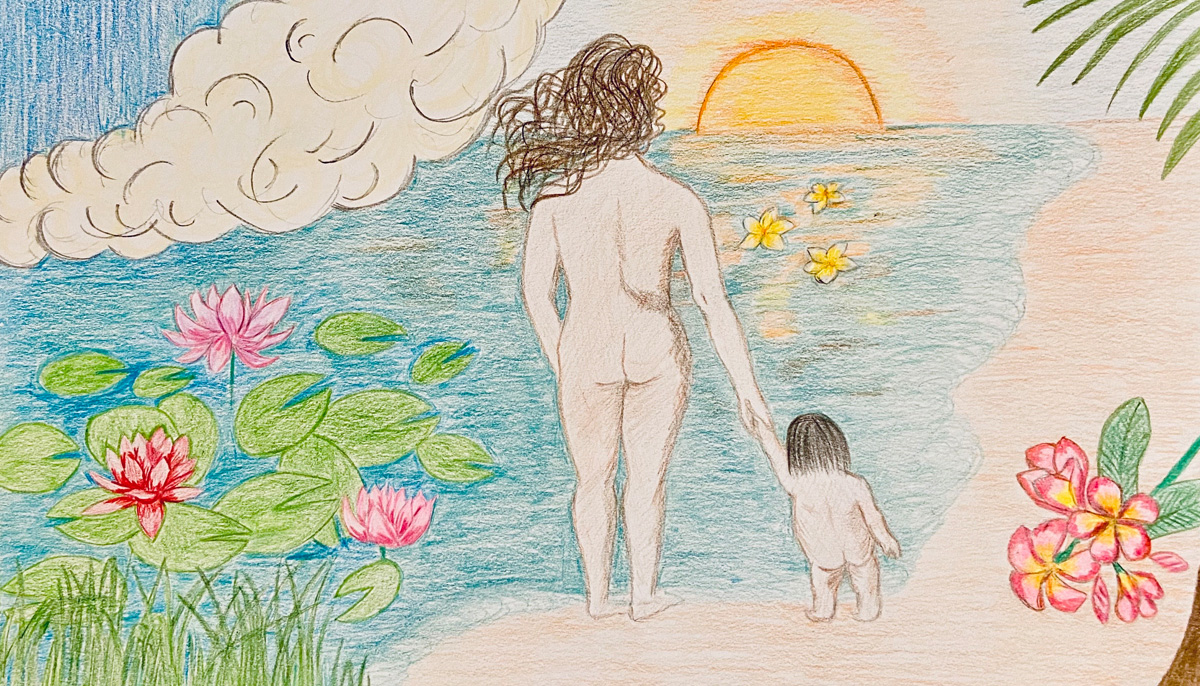

I am standing on the shores of a beach with my newly born baby, holding her hand. We are watching a bright orange sun set on the water. Three plumeria blossoms float gently on its surface, their yellows and whites merging with the orange and silver sea. They are my babies who were never born. The ones I cast upon the water in the shape of flowers during a May 2019 sunset on Kawela Bay. The drawing is an homage to them, like the letter I read when I set them on the warm Hawaiian sea.

In this image, I am with all my babies.

To our left, lotus flowers emerge from turquoise waters. “No mud, no lotus,” I thought when I drew them. This Buddhist adage had carried me through the year of losses, pregnancy and eventual birth. Just above, clouds of mist swell from the base of a waterfall. Its dark and wild waters cascade down the top left corner of the page with no crest in sight. The billowing base marks the end of my tumultuous journey. At last, I am at my destination, standing on the shores of a beach with my newly born baby, holding her hand.

Our brief time sharing a body taught me so much of generosity, love, and impermanence.

Before I gave birth to my first child in March 2020, I experienced three early miscarriages. The first two were “chemical pregnancies,” pregnancies that register positively on urine or blood tests, but hCG hormone levels are too low to maintain the pregnancy. These very early pregnancies, marked by losses, never manage to appear on ultrasound screens; they remain entirely invisible. In fact, chemical pregnancies occur so frequently and so early that many people miscarry without realizing it.

I knew I was pregnant because I chose to take early pregnancy tests and then requested blood work for confirmation. Had I waited, would I only have known my period was several days late? The third miscarriage, however, lasted six weeks. I knew for five days before I miscarried that the pregnancy was nonviable.

Waiting for a miscarriage entails a special suffering. As a meditator attuned to mindfulness of the body, I sensed subtle changes in mine before I saw faint positive lines on pregnancy tests—flutters and tingles, heaviness and bloating that did not correspond with my usual PMS. My first test confirmed these sensations as pregnancy, and each time after, they triggered hope before testing. During the days I waited to miscarry, I felt a grave disconnect between body and mind. My body still hummed with the vibrations of early pregnancy; my mind mourned an impending loss. When the loss finally materialized, I experienced a personal, embodied grief like never before.

For a long time, I was angry at myself for the emotional intensity of my experience. It was abundantly clear that my deep suffering resulted from my longing to have a child. I knew the suffering was impermanent, but I had a harder time grappling with the ferocity of my attachment to motherhood. Why did I throw myself so immediately into urine and blood tests only to confront shadowy lines and numbers declaring I was barely, maybe pregnant? We had just begun trying for a baby. Why did I have no patience?

I have since realized that each of these questions carries an accusation: I blamed myself, saw my self—an isolated clinging mind and flailing body—as the root of my misfortune. Intellectually, I understood miscarriages result from certain physiological causes and conditions. As a Gender Studies professor, I also believe that while I regarded these clinically invisible embryos as “babies” because of a desire for motherhood, other pregnant subjects could just as validly consider a pregnancy’s end as passing reproductive tissue.

Given my history of depression, I felt a familiar, hollow well of sadness grow at my heart’s center. I faced my long-standing fear that something was inherently wrong with me. I struggled to find appropriate means to grieve an invisible loss. Because the loss was so early, so unrecognizable, I wondered whether I even had a right to grieve. “I feel so much grief,” I told a loved one. “For what?” they responded, “Something that wasn’t real?” Yet others recited the intendedly reassuring phrase, “at least now you know you can get pregnant.” The statement was not reassuring.

I remember spending hours online, searching the phrase “Buddhism and Miscarriage.” I did not find much then. Fortunately more articles have appeared since, such as Mindy Newman’s essay “Healing from Miscarriage,” where she adapts the Buddha’s “Parable of the Mustard Seed” for those who have experienced pregnancy loss. I shuddered whenever I encountered entries attributing pregnancy loss to one’s negative karma. Eventually, I found a teaching by Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron offering an alternate perspective. According to her, each being is born with a designated “karmic lifespan.” Sometimes, an untimely event leads to death before the fulfillment of this lifespan. As a result, “when that person takes rebirth, often […] there’s a miscarriage, or a stillbirth, or the baby dies when it’s quite young because it just has that little bit of human karma left in that particular life to experience.” This teaching, along with the Buddhist doctrine that a being in the bardo (state between life and death) is karmically attracted to particular parents, provided comfort. They allowed me to consider my womb as worthy and generous rather than pathological.

In searching how to process grief, I discovered Mizuko Kuyo—“water child memorial service”—a Japanese Buddhist ritual that honors children who are never born due to miscarriage, abortion, or stillbirth. In this priest-led ceremony, grieving parents choose a statue of the Boddhisatva Jizo—protector of deceased children—to represent their loss. They then create an offering, a red bib or bonnet, that Jizo wears in its final resting place. The intricate beauty of the ceremony helped me realize I too needed a ritual, a way to honor these embryonic endings, to materialize their absence, to make them something that was real.

On a trip to Molokai, Hawaii, in May 2019, I sat on a beach at sunrise and wrote a letter to my recently lost baby. As I lay pen to paper, crying, bearing witness to the ocean’s ebb and flow, the cool morning mist brushing softly against my skin, I understood the meaning of the Buddha’s phrase “ten thousand joys and ten thousand sorrows.” As expansive and tumultuous as my sorrow was, I appreciated the soothing splendor of the literal arising and passing of things before me.

I shared with my never-born child the expansive nature of their sojourn within me. How every single day, I asked them to take whatever they needed from me. How I had called to my female ancestors, envisioning many warm brown hands cupped around my womb, cultivating life. How the intimacy of our brief time sharing a body had taught me so much of generosity, love, and impermanence. I asked for forgiveness for holding on so tight.

Several days later, on the shores of Oahu’s Kawela Bay, I laid plumerias in the water at sunset and read the letter out loud. The wind carried my words as the water carried the flowers gently out of sight. My heart opened to compassion.

With time, I no longer see myself as an isolated clinging mind and flailing body, but as someone who knows the suffering that comes with having a body capable of bearing a child. I have learned of so many others who share the heartache accompanying pregnancy loss. And since becoming a mother, I am working on a spacious, loving attachment to my children rather than a craving one. I aim to be present for these beings, to create space for their experiences, to hold them gently as they too encounter suffering and impermanence in this life.