In the fall, my brother Cam told me he’d been having trouble sleeping. He’d recently retired after a long career, and I thought maybe the sudden abundance of free time had set his circadian rhythms adrift. We lived in different cities and talked on the phone only occasionally, and even though he wasn’t the sort of person who complained easily about minor annoyances, I expected that by the next time we spoke, he’d have worked it out.

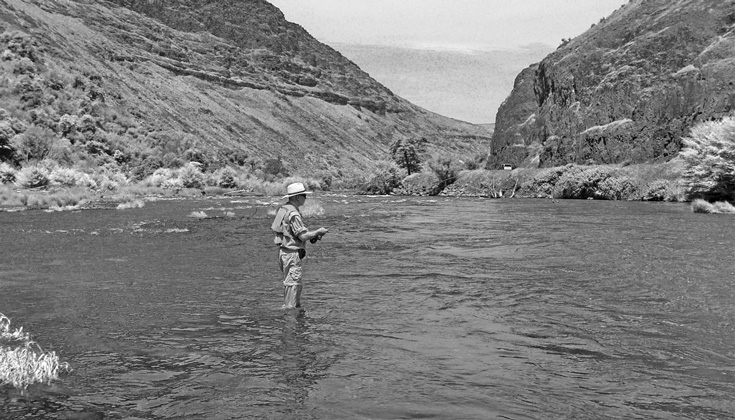

Cam loved catch-and-release fly-fishing and spent as much time as possible knee-deep in cold, fast water. He lived in Portland, and his favorite steelhead river, the Deschutes, ran through the Columbia Plateau a couple of hours east of the city, across the Cascades. He’d built a little house overlooking the river, where he and his partner, Ingrid, spent time whenever they could.

A couple of weeks after my conversation with him, Cam was fishing a river in British Columbia when Ingrid got a call from the lodge where he was staying. The staffer said Cam was confused about what day it was and kept muttering that someone had gotten into his phone and reset the date. This was so unlike my brother—a genial and gregarious man with an extremely sharp mind—that Ingrid considered having him airlifted to a hospital right then. But there was a doctor at the lodge and much of the time Cam seemed all right, so they let him finish his trip, with Ingrid checking in daily. When Cam flew home, she took him straight to the ER, just in case, but the doctors concluded he’d simply been affected by the Benadryl he was taking to help him sleep.

Three weeks later, Cam went to a neurologist who specialized in sleep disorders, but by this time he also had a chronic cough and balance problems. The doctor ordered more tests, and Cam continued to deteriorate quickly, even as they awaited the results.

When I was eight and Cam was fourteen, he took me into my bedroom, told me to take off everything but my underwear, then wrapped me head-to-toe in some extra-long elastic bandages. When I was left with openings for just my eyes and nostrils, he went into the closet. He soon emerged, stark naked and carrying a large hunting knife, then started leaping around in what appeared to be some sort of tribal dance.

He kept getting closer, waving the knife, but there wasn’t a lot I could do except lie there in puzzlement and increasing alarm. Then on one swooping pass with the knife—accidentally but inevitably, one might say in hindsight—he misjudged his swing and gashed open my forehead just above the eyebrow. This pretty much brought the festivities to a halt, so we used the bandages to stanch the blood. He unwrapped me and I got dressed.

“Probably better not to tell Mom and Dad how you got the cut,” he said.

I knew that anything I made up would almost certainly be more plausible than what had actually happened. Ultimately it didn’t matter, though, because our parents—perhaps wisely—opted not to inquire. As for the perplexing ritual itself, I made the same choice.

Buddhism puts a lot of emphasis on impermanence, which partly means debunking our most cherished of narcissistic delusions — that we’ll somehow live forever.

In any case, my idolization of my brother survived. Cam was an Eagle Scout, so I became an Eagle Scout. He wanted to be a writer, so I decided I did too. Of course, later he had the sense to give it up and go to law school, but I persisted in my mule-like way, which ultimately amounted to an informal, lifelong vow of poverty.

When I was growing up, though, he helped me out just by existing. Our mother had what would now probably be called borderline personality disorder. She’d suddenly erupt in screaming rages, sometimes two or three times a day. Often there was no discernible correlation between anything I’d done and these explosions. This left me a little jittery, to put it mildly. I had my first ulcer when I was seven and, because I was a child, I considered this normal and wondered why my friends didn’t have ulcers too.

When I was fifteen or sixteen, I found that I enjoyed meditation, though I don’t remember how I learned about it. As soon as my mother discovered I was meditating, she forbade me to do it. Nevertheless, it calmed me, so I crept out of bed at night to sit cross-legged on the floor anyway. As I sat there, I knew that, just as I’d snuck from my bed, in nearby blocks my few precious friends were also sneaking from theirs and then from their windows, so they could drive around, smoke weed, experiment with sex, and earnestly discuss Stranger in a Strange Land. Meditation didn’t seem nearly as fun, but even then it was dawning on me that fun wasn’t always the point.

Once, when Cam was home for the summer, he put an arm around my shoulders and told me he knew what I was going through, urged me to just survive it until I could get the hell out—to college or whatever I wanted to do. It was as if I’d finally been granted permission to inhabit my life with some semblance of agency instead of endless, flinching recoil. He followed up by teaching me to play the guitar and introducing me to the music of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and a few others I came to love. Aside from the pleasure of learning the instrument, he thought it might help me with girls. Much to my amazement, after a few months of diligent practice, it did. My gratitude grew.

Later, when I was twenty, I dropped out of school and drove my rattletrap Falcon across the country to live with Cam and another guy in southeast Portland. He was teaching in a funky alternative school by day and playing in a rockabilly band at night, and it quickly became clear he no longer had a lot of time for my neurotic growing pains. Even so, he did what he could to instruct me in various manly arts, including some that might have been construed as a convenient way to get rid of me. He taught me how to ride a motorcycle and use a chainsaw, for example—though in fairness, not at the same time. Mainly, though, he just let me be, which was probably the wisest course for both of us. I stayed for eighteen months, but then, lonely and tired of the cold rain, I headed back east for another try at college.

By January, Cam was continuing to deteriorate. The neuropsychometric testing showed problems all through his brain, but his spinal tap and EEG were normal. There was no cancer and no sign of infection or autoimmune disorders, but he was becoming increasingly anxious and paranoid. Of course, the problem with ruling out conditions you can treat is that it leaves you with the ones you can’t. The neurologist had grown concerned about a rare condition called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

CJD is one of a family of disorders known as spongiform encephalopathies, because they leave the brain riddled with tiny vacuoles, like a sponge. All such diseases are caused by the spread of misfolded proteins called prions, and they share symptoms including progressive dementia, behavioral problems, sleeplessness, and a relentless degeneration of motor control. They’re usually fatal within a year, and by the time you’re symptomatic, there’s little to be done.

Or as the journalist Thomas Sleigh once wrote of working in dangerous places: “Everything is okay until it’s not okay, and then it’s too late.”

In early February I flew to Portland. Cam looked exhausted, much older than his years, and he often seemed confused. He’d been an excellent attorney and a mentor to many younger lawyers, and I was shocked to see him in this reduced state.

The morning after I arrived, an ice storm shut down the city, but he wanted to go downtown to the federal courthouse. Several years previously he’d helped found the Deschutes River Alliance, which had recently challenged an upstream dam’s release of relatively warm water into the river on the grounds that it could harm steelhead runs. A hearing was scheduled that day, ice storm or not. The buses were chained up and running, so I helped him across the street to the stop. At the courthouse, the judge asked a lot of technical questions and the lawyers argued with each other. It was all Greek to me, but Cam listened raptly and seemed to follow the discussion with pleasure.

When the hearing was over, we went outside and started looking for a bus. I hadn’t paid attention to the bus number on the way downtown because he seemed to know the way, but now he insisted that we needed a Number 6, so we walked block after block in the freezing rain looking for one. Cam declined my arm and shot along in a wavering, stiff-legged stride that brought to mind the Keystone Kops, and which might have been amusing had amusement been his intention.

Finally, getting cold and impatient, I asked a woman at a bus shelter what number we actually needed. She said we needed an 8, which would arrive in a couple of minutes. Cam jabbed his finger at me and insisted she was wrong. If I’d been a better man, I’d have put an arm around him as he’d once done to me and gently suggested that we try the Number 8 anyway. I was not a better man, unfortunately, and we had a brief shouting match, at the conclusion of which the bus rolled up and I pleaded with him to just get on the damn thing. Mercifully, he capitulated, and we went home.

That evening, he seemed more himself and took us all out to dinner: Ingrid, me, and two of his adult children from an earlier marriage, Christine and Geoff, as well as their partners. Cam joked and laughed, and if he did, occasionally, seem to withdraw from the conversation and retreat into solemn silence, who could blame him?

Later, I was sleeping in the spare attic room when around midnight I awakened to a house-shaking boom from below, the sickening sound of flesh and bone slamming into floorboards. Cam had fallen, and now he howled in pain and rage. I was starting downstairs when Ingrid called up and told me I should stay put—she had it, it was okay. This had started just recently, it seemed. I went back to bed, but later it happened again.

In our thirties and forties, Cam and I saw each other occasionally, but our lives took us in different directions. After earning his law degree, he entered the corporate world, whereas my adolescent interest in meditation ultimately led me to becoming a Buddhist. I met the Tibetan teacher Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, moved to a small Oregon town to study with him, and worked as a freelance writer and photographer so I could set aside blocks of time for formal retreats.

To Cam, my life in those days seemed anarchic. He could be judgmental, and several times, if we were together for some sort of family event, he made a passing reference to my laziness. These were always couched as jokes, and they sort of were, but they also sort of weren’t.

Things changed, thankfully, when my first novel came out in 2011. He liked the book, and when my tour took me to Portland, he came to Powell’s and beamed all through the reading. Afterward, he bought dinner for me and several old friends. And so, after years of careful distance, we started circling back toward comfort with each other.

As it happens, Buddhism puts a lot of emphasis on impermanence, which partly means debunking our most cherished of narcissistic delusions—that we’ll somehow live forever.

Most Buddhist teachings harp on the sort of relationship with death that, in the Western canon, Montaigne espoused in the 1500s. In one essay he wrote, “Where death is waiting for us is uncertain; let us await him everywhere,” and provided a grim inventory of untimely demises in support of the proposition. These included being beaned by a tortoise dropped by an eagle (Aeschylus); sudden death during sex (a long list of men, one of them a pope); and getting whacked in the temple by a tennis ball (Montaigne’s unlucky brother). “Long life and short life are by death made all one,” Montaigne added. He probably would have made a good Buddhist.

Contemplating impermanence rubs your nose in the grim realities of universal mortality, certainly, but it also prods you to pay attention and to value each moment of existence you have.

At the end of my February visit, after the night of terrible falls, I brought my bags downstairs and put them by the door. Cam was resting on the couch. I sat down beside him, then took him in my arms and told him I loved him. I wasn’t sure how this would be received, and I almost didn’t do it, because if he pushed me away or made some dismissive joke I didn’t think I’d be able to bear it. But he hugged me back and told me he loved me too. It was the first time in our lives we’d spoken the words to each other.

A couple of weeks afterward, Cam and Ingrid went to see a prion disease specialist. By then, things were dire. “His personality was changing and he was having auditory hallucinations,” Ingrid told me later. “He had trouble with everything—sitting, standing, moving—and he couldn’t remember how to do the most basic things. I could see that the person he had always been was leaving.”

The specialist finally diagnosed CJD, based on Cam’s latest MRI. Ingrid made arrangements to move him into assisted living.

Surgeon and author Atul Gawande wrote, “The battle of being mortal is the battle to maintain the integrity of one’s life—to avoid becoming so diminished or dissipated or subjugated that who you are becomes disconnected from who you were or who you want to be.”

My brother was losing that battle. When I visited him in the assisted living facility that May, I found him lying quietly in a hospital bed by a window with a view of downtown Portland. Warm, late afternoon light fell on the buildings outside. Occasionally he’d mutter a few syllables, but I couldn’t tell what he was trying to say.

I’d taken one of my favorite photo books with me, David Muench’s American Landscape. I sat in a chair beside his bed, held the book where he could see it, and turned the pages through pictures of dawn over the Blue Ridge, of moonrise in the Adirondacks, of the mountains of North Carolina and Maine and Colorado. He stared at the photos but I couldn’t gauge his reaction, so after a few minutes I put the book aside and just sat quietly with him.

The next day he was in his wheelchair when I arrived with my wife, Patti. We greeted and hugged him, but he just stared. We sat on the couch, and I found a book I’d recently given him, The Names of the Stars, Pete Fromm’s memoir set in Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness. Ingrid had already read most of it to him, so I picked up where she’d left off.

I read: “I soldier home, trying to see everything this last time, remember which big dug-out hole was the badger’s, finding the best still-visible wolf tracks. My last hike through the Hansel and Gretel stretch is not one I’ll miss.…”

Which was as far as I got. My voice wavered and I had to put the book down. Patti bailed me out, then, by talking to him; he watched her and a brief smile flickered across his lips. She asked if we could get him a snack from the cache they kept for him, and he startled us by whispering, “Maybe some carbs.” I’d had no idea he was tracking anything we said, but we gladly brought him cookies.

Later, when we left, I hugged him and told him goodbye, and I held on a while, because I knew it was the last time I’d see him.

“It’s hard to watch the person you love disappear,” Ingrid told me. “You try to reclaim memories from previous years, because the recent ones aren’t good.”

Of course, one reason dementia is so troubling is that it raises questions about the ephemerality of the self, about who we really are. Do we have an essence? If our minds and personalities can deteriorate to the point that we and our loved ones become unrecognizable to one another, does this disprove the possibility of a soul? And if we did have one, how would we know?

Even Buddhists disagree about such things. From one viewpoint, there’s a kind of continuity—a mindstream—that finds its way from incarnation to incarnation. From a larger perspective, this is just another illusory aspect of the display of existence.

Cam’s grave is remarkable mainly for how unremarkable it is. He was successful and reasonably wealthy, the kind of man you’d expect to be interred amid lush grass and panoramic views, near the resting places of loved ones.

He is, in fact, buried among strangers in a tiny rural graveyard on the plateau south of the Columbia River Gorge, a short drive from the Deschutes River. When Patti and I visited, the expansive, undulant wheat fields of the plateau had already been mown to pale stubble in the late summer heat. Smoke from forest fires had erased what little view there may have been, and the air was still. A few trees provided half-hearted shade, but overall the place felt barren, remote, and forsaken.

Cam’s grave, at that point, was just a mound of dirt. We’d brought a piece of petrified wood, given us by Ingrid’s sister, to serve as a temporary headstone. Ingrid had come earlier with a colorful blown-glass fish’s tail, which she’d stuck into the ground so it looked like a steelhead had just dived below the surface.

I talked to Cam a little, said goodbye again, then stood in the dust and wept. It seemed possible that I’d never see his grave again, because what would I be visiting, really? He didn’t want to be embalmed and was buried in a simple pine box. Nature would do its work quickly, and soon I’d be visiting nothing but my own memories, which I can visit anywhere. My tears were partly for him, but when you mourn your brother, you also mourn for yourself—mourn at once for the past, forever lost, and for the future, forever empty of him.

In such circumstances, the word itself—forever—sheds its soft abstraction and acquires the solidity and weight of granite. It’s as undeniable as the body in the box below the ground, which, ironically, invokes that infinitude precisely because it will soon disappear.

Eventually a little breeze came up, just enough to ripple the leaves, as if the land had finally allowed itself a brief, warm exhalation. We drove down the canyons to the Deschutes, where rafters paddled by on this fast, cool river my brother had fought to save, laughing and splashing each other.

The Deschutes reminded me of an old story that after we die, we wander a vast desert, for weeks or months or years. On that tormenting journey all we can think about is the life we’ve lost, the things we could have done better, the love we withheld and the hatred we did not. But then, eventually, we come to a river. We wade in and begin to forget that life. Our attachments and regrets dissolve, and by the time we’ve crossed over, the river has carried our memories away. This new innocence is essential, for otherwise how could we ever emerge from the water and begin again?

As best I recall, I heard this from a Buddhist teacher, but I’m not convinced it describes a particular Buddhist cosmology. It encompasses aspects of the Bardo Thodol and of Greek mythology, where the river of forgetting is called the Lethe. The story is impossible to prove except in the obvious way, which naturally makes it challenging to file a report. It feels right to me, though, because my brother, and others with similar diseases, just seem to cross that river a little sooner than anyone else, where we can all see them do it.

Later, when I asked Ingrid about the isolated graveyard, she told me that usually the air is clear and there’s a beautiful view of Mt. Hood. I realized I’d misjudged the place; it was simply unassuming, and with the mountain in sight it would have been lovely.

There will be visitors from time to time—Ingrid, Cam’s kids, his friends—but over the years there will be fewer. After four decades or five, there won’t be any at all.

I like to think he would rest easy, knowing this, though as with so many aspects of what happened to him, I can’t even really say why.