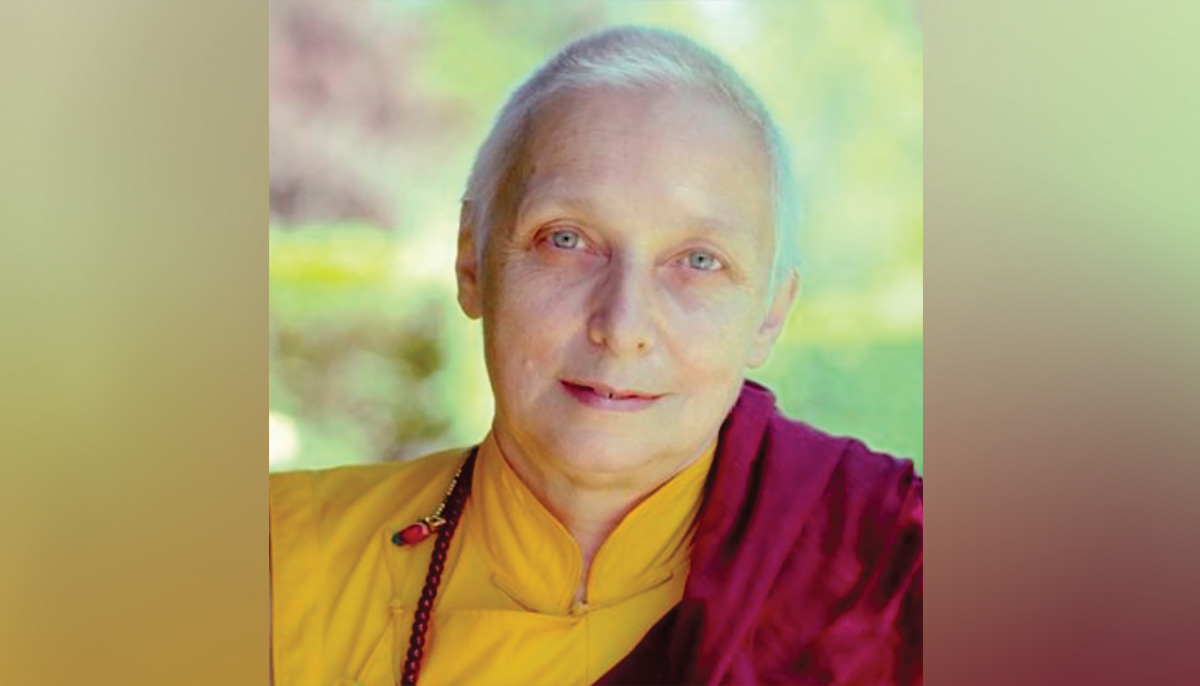

Freda Bedi was born Freda Houston above a quaint watchmaker’s shop in Derby, England, in 1911. Tall, blue-eyed, and with an imposing manner, she wore many hats: Oxford scholar, professor, social worker, champion of women’s rights, wife and mother of four, Gandhian revolutionary (even imprisoned for his cause), and one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun.

Freda’s destiny was sealed when she won three scholarships to Oxford, where she met and married Baba Pyare Lal Bedi, a direct descendent of Guru Nanak, founder of Sikhism. She followed him to the Punjab, then still under British rule, and found herself at home there.

In India, she threw herself into political activism and arduously studied many spiritual paths, looking for her own. Finally, she found it in Burma, when, in 1953, she took personal instruction from the eminent Vipassana master Sayadaw U Pandita. The result was what she called an “enlightening experience” that changed her life forever.

In 1959, Indian prime minister Nehru sent Freda to refugee camps in Assam and West Bengal to aid the tens of thousands of Tibetans who were pouring in, bedraggled and traumatized, to escape the Chinese forces who had invaded Tibet.

What Freda achieved in her sixty-six years was extraordinary.

While doing this work, she met the young Tibetan lama Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Immediately recognizing his special qualities and, in her words, “spiritual purity,” she took him into her family home in Delhi, tutored him, and arranged an Oxford scholarship for him. This led to Trungpa Rinpoche’s great contribution to seeding Western Buddhism, which included founding Samye Ling in Scotland, the first Tibetan Buddhist center in the West.

Freda was also pivotal in introducing the Western world to the Sixteenth Karmapa, the head of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. He was her guru, and their relationship was close. For a while, she even lived in a room directly under his at Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim.

Freda persuaded the Karmapa to make his first tours to the U.S. and Europe, while he, in turn, persuaded her to take the bhikshuni ordination and, thus, crash through the spiritual glass ceiling, which had relegated nuns in the Tibetan tradition to the status of novices. In becoming the first known woman of any nationality—including Tibetan—to become a fully ordained Tibetan Buddhist nun, Freda paved the way for scores of others to follow.

But there was still more she achieved. Amid the chaos of the Tibetan diaspora Freda saw that Buddhism could come to the West primarily through the young tulkus (reincarnated masters) then living in exile in India. To help make this happen, she opened the Young Lamas Home School in Dalhousie, India, where she tutored tulkus in English and contemporary Western customs. Many of her students there did ultimately find their way to the West and became influential teachers. She also had big plans for the nuns and founded the first nunnery in exile.

Freda was a doer, undauntedly following her own vast vision, and what she achieved in her sixty-six years was extraordinary. She is one of the most colorful, influential, and unsung heroines in contemporary Buddhist history.