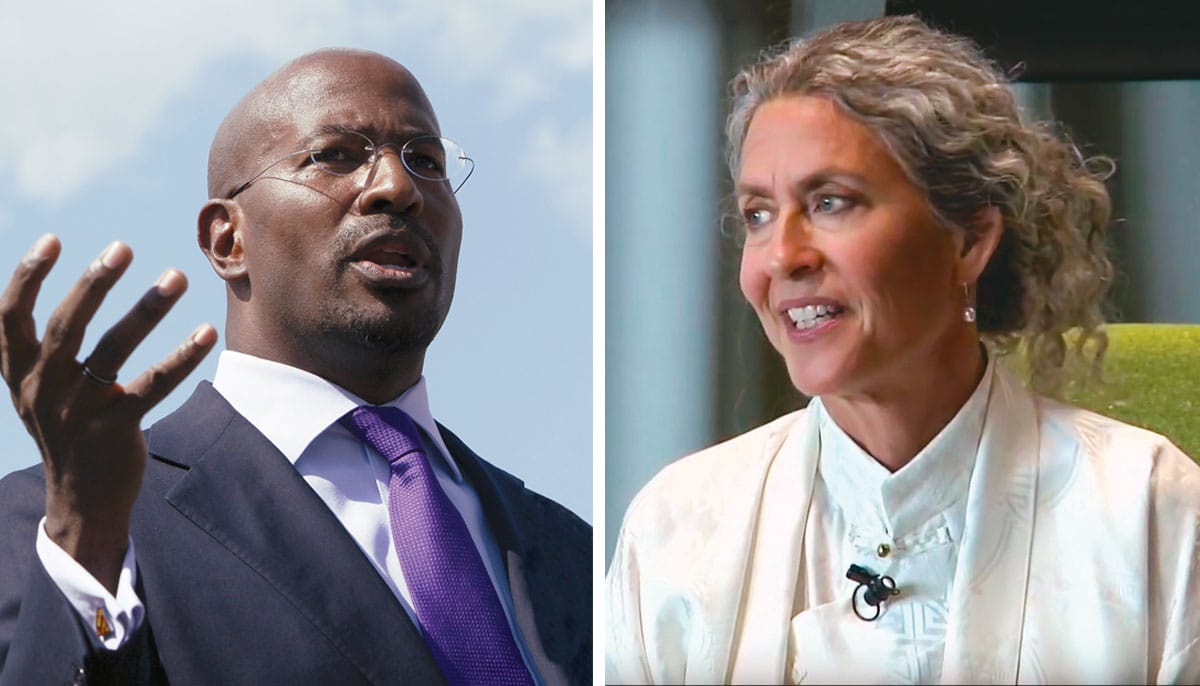

Lion’s Roar: How would you assess the state of love in American society today?

Lama Tsomo: This moment in time is filled with all kinds of extremes, from environmental politics to the economy. It is bringing out both a lot of love and a lot of othering. Van and I have talked a lot about the temptation to fall into “us” versus “them”—how easy it is to feel part of a group by othering somebody else, how tempting it is to fall into that when we’re afraid. Yet this time is calling us to move past that urge into loving everyone and finding solutions for the sake of everyone.

Van Jones: It definitely feels like we are in a spiral of tribalism. What’s interesting about tribalism is that love is present—but it’s narrowly focused. Trump voters feel that they’ve been left out, laughed at, or pushed aside by an emerging American majority that doesn’t look like them and doesn’t speak the same way they do. There’s an upsurge of love for self, but with a Trump-style wall around it.

The challenge is to get people to extend the boundaries of the love they feel without giving up pride in who they are.

Similarly, other groups are also coming into a form of self-love or self-expression, whether we’re talking about transgender people, people with immigrant backgrounds, or young African Americans marching against police brutality. They’re expressing a love for themselves, and for people who are like them. But that love doesn’t always extend to people on the other side of the police line. That’s understandable, because of the long history of the system abusing its power. And yet if neither side reaches out, we get stalemate at best—or a new kind of civil war at worst.

The challenge is to get people to extend the boundaries of the love they feel without giving up pride in who they are, where they’re from, or what their faith is. It’s about creating as many opportunities as possible for people to rediscover those connections.

Can we find a love that bridges differences without sweeping very real differences of opinion and policies under the carpet?

Van Jones: In a democracy we get to disagree, which is called freedom. That’s the point. In a dictatorship you can’t disagree. But there’s a kind of totalitarianism on both sides today.

I think liberals in the United States have an almost colonial attitude toward the red states, like Southerners are just unwashed heathens. Liberals too often act like red state voters need to be conquered or converted to the NPR religion, and then all will be well with the republic. Similarly on the right wing, everything about liberals is seen as perverse, weak, or corrupting. So the first step is remind ourselves that we need each other. Liberals need conservatives, and conservatives need liberals, to make the country work. No bird can fly with only a left wing or only a right wing.

I would say we have a heart problem and also a head problem. The head problem is remembering that we’re not enemies, even when we disagree. We should disagree—and disagree passionately—but then expect some better answer, some higher synthesis, to emerge from the conflict.

The heart part is all the disciplines and practices that allow us to do that better than we might otherwise. We need to stay centered, grounded, open—able to resist when we need to, but also bend when we need to. That’s hard. These spiritual practices help us execute what both our minds and our hearts know is right—to stand for what we believe in—in a way that allows something beautiful to emerge from the conflict.

Lama Tsomo: That’s why all spiritual traditions exercise both the head muscle and the heart muscle. Inner work goes hand-in-hand with outer work to create something powerful that can manifest in the world. An obvious example is the Dalai Lama. He has accomplished extraordinary things by exercising both his head and his heart in incredibly trying circumstances.

What is his secret?

Lama Tsomo: I’m going to mention the four immeasurables: loving-kindness, sympathetic joy, compassion, and equanimity. When you practice the four immeasurables, as the Dalai Lama does, then love for yourself, your favorite people, and your tribe moves out in ever-greater concentric circles until it’s love, compassion, and sympathetic joy for everyone. If you do the inner work of that practice in the privacy of your home, then your outer work has a lot more power because you have exercised your love muscle.

We don’t want to eliminate anyone from our love.

Neem Karoli Baba said, “Never throw anyone out of your heart.” As soon as I eliminate one person from my heart I make my own heart smaller, and I don’t want that. That elimination of people can extend to whole groups. We think that if they weren’t there, it would be much easier to solve all our problems. So we eliminate them from our heart.

But our heart doesn’t want to have a boundary around it. We don’t want to eliminate anyone from our love. When we think of Martin Luther King, Jr., the Dalai Lama, and other revered and respected figures, we see that this is the secret of their power to help the world.

Van Jones: In terms of specific practices we can do, there are all kinds of things conspiring now to make fear and division greater.

Social media is one of them. Algorithm-enhanced tribalism is very, very dangerous, because when you don’t understand where the other person is coming from, you just see these nasty, snarky, one-sided tweets. So your view of them becomes more exaggeratedly negative, and you’re more scared and stupid with every click and swipe.

I decided I didn’t want to be victimized by that. So as a practice, I went and searched for every right wing, conservative, white nationalist I could find and followed them all. Now my Instagram feed doesn’t make me feel warm and fuzzy, but maybe you just have to get your warm and fuzzies someplace else. I have a better understanding of where my opponents are coming from, and that informs my approach.

I just think there’s a kind of practical fight here. It really is the case that Donald Trump wants to deport millions of people, that Muslims and Jewish people are being harassed in almost unheard of numbers. At the same time, if you are a white, Christian male in the red states millions of liberals need to hear nothing more to not like you. There are real threats out here. That’s the reason we need these great practices. They give us a North Star to get through these periods better, not bitter.

A lot of people these days are debating the usefulness of anger. It can fuel protest and resistance to injustice, but it can also cause more division and hate. Is anger useful now or not?

Lama Tsomo: There’s a principle in Tibetan Buddhism I’ve found really helpful—the difference between anger and wrath. Anger is somebody saying something insulting and you wanting to punch them. Wrath is something quite different.

In the New Testament there’s the story about Jesus driving the merchants from the temple. His actions were fierce and appeared angry, but they were actually coming from love and compassion. In Tibetan Buddhism, we contemplate some ferocious archetypal figures that are realized beings. You wouldn’t want to meet any of them in a dark alley. We contemplate them so that we can feel compassion in a ferocious form.

Power without love is destructive. Love without power is, well, powerless. What is the right relationship between love and power?

Lama Tsomo: Human beings are brilliant animals, and we can find all kinds of creative ways to manifest either wonderful or terrible things. Love combined with insightful wisdom is very powerful, but just having intelligence without the motivation of love and compassion creates things like the atom bomb.

As Starhawk pointed out, there is power over, power with, and power within. If we cultivate all three of these types of power with love and compassion, then something positive that affects the whole society gets to happen.

On the inner level, this can happen because, as many great religious figures and scientists say, we’re all absolutely connected. The late physicist David Bohm said that at the quantum physics level, there’s no difference between inside and outside your skin. That begins to blow apart our sense of boundaries. It shows us that the true nature of things is that we’re all connected.

Bohm was saying that if we act according to how things really are, it’s probably going to go better. We’re going to be happier and we’re going to produce happiness around us. Anytime you’re off in your understanding of how things are, you’re going to cause suffering for yourself and for others. That ripples out into society in all kinds of ways.

Van Jones: One of the great powers that Nelson Mandela had over his enemies was that he actually had a vision of South Africa in which the Xhosa, the Zulu, the Afrikaners, and others all had a place of honour, dignity, and respect.

If we don’t make it clear that our intention is for everyone to be free, then we just get on a seesaw.

If I have any quarrel with the present progressive movement it is that there sometimes seems to be too little space for our opposite numbers to be free too, and for them to feel dignity and respect. Speaking to a woman, a person of color, LGBT—or speaking to an immigrant or a Muslim—it seems unfair to say to them, “You have to get free, and you also have to free the people who are holding you down.” It is unfair, and it is unjust. But it is absolutely necessary.

If we don’t, from the start, make it clear that our intention is for everyone to be free, then we just get on a seesaw. We’re up for a while, and then we’re down for a while. We just saw that from Obama to Trump. What has yet to be rediscovered, in the U.S. context, is a third way out—one that allows your love for your own group to be so profound that it requires you to find a way to feel and demonstrate love for your so-called opponent.

What is the role of spirituality in political life? Can there be deep change, the kind the world needs, without spiritual practice at the root of it?

Lama Tsomo: We humans are herd animals. It seems that every great religion has figured that out. There are churches, temples, mosques, and synagogues, and in Buddhism there is sangha. Anytime we want to change our habits, we’ve had far better success doing it in groups than all alone. So there’s something to be said for that.

I would like to make a distinction between spirituality and religion, because they aren’t quite the same thing. Spirituality can be a very personal experience, while religion provides support from other people who are trying to move in the same direction. But sometimes religion gets tribal, and then it becomes “us” against “them.”

When the Israelites were freed from Egypt, God parted the seas, which then crashed in on the Egyptian army. When the Jews rejoiced, God said, “Why are you rejoicing? They’re my children too.” With our herd instinct tendencies, we sometimes forget that.

There are religious people who are falling into us vs. them, while other churches, synagogues, mosques, and so on are reaching beyond that. I think it’s quite possible to do both: to have your intimate spiritual community, your sangha, your congregation, as well as reaching out to people in other congregations. When we do reach out in a respectful way to somebody across the divide, that can allow the kind of change we need right now.

Van Jones: Well, all human institutions are shot through with all kinds of foibles and problems. Also, all human institutions tend to assume aspects of the society in which they exist. I think it’s a mistake to get madder at religion and religious folks than we get mad at anybody else. People who run corporations, who run sports teams, who create television programs, are also infected by human foibles and societal biases. I think we do ourselves a disservice when we make totalizing statements about religion, because it tends to bypass a deeper truth.

Is some form of spiritual practice or understanding necessary for us, as a society, to really change how we relate to each other?

Van Jones: What I would say is that I can’t do the work that I’ve chosen without a spiritual grounding. I am blessed to get to talk to some of the poorest people in the country and some of the richest people in the country, often in the same day. Because I’ve been exposed to different ways of thinking and being, I have a better chance to actually learn something and be a contributor than I would otherwise.

Lama Tsomo: I really had to sit with myself. I tried freestyle meditation, but that was not very successful. So I decided to pick a time-honored method that has been refined over a very long time. Luckily, the world is full of lots of lineages that are replete with wonderful tools that I would never have thought of myself.

I really appreciate the methods I’ve learned. I found a master who is very accomplished in them. Personally, I have found it really helpful to pick tried-and-true methods. I’ve also found it helpful to be with other people who have a similar goal.

For that reason, I picked an established religion, rather than trying to reinvent the wheel for myself. But I think if people just sit quietly for a few minutes a day, not having to respond to things on the outside, that’s a great place to start.