Christopher Moltisanti walks into a bakery to buy pastries for his Mafia boss. He takes a number—thirty-four—and waits for what feels like half of New Jersey to get served. Then Christopher’s number comes up and he’s about to order when Gino, yet another customer, walks through the door. The clerk, talking past Christopher, asks Gino what he can get for him.

“Whoa,” says Christopher, slamming the counter. “Number thirty-four right here.”

“He was in line,” says the blond clerk. “He just went out to get gas in his car.”

“Oh, so I can go out, fuck your sister, come back Saturday—I go to the front of the line?”

“I said he could.” The clerk’s tone is harder than week-old bread.

“Hey, poppin’ fresh,” says Christopher. “I’m in no fucking mood today. I’m next. Now get a fucking pastry box.”

But still the clerk turns to Gino and insists on serving him, even when Gino says it’s okay, that Christopher can go ahead of him. So Christopher opens the bakery door for Gino. “Take a walk,” he says. Then Christopher flips the open sign to closed and whips out his gun. “What is it? Do I look like a pussy to you? … I’m serious—be honest. I won’t get mad.”

“No,” stutters the clerk. “I’m sorry.”

“Get a pastry box,” says Christopher. Then, when the clerk doesn’t hop to it fast enough, he shoots the floor close to the clerk’s feet. The clerk quickly fumbles for the box and fills it with cannoli, sfogliatelle, and napoleans. He closes the lid and hands the box to Christopher.

“Next time you see my face,” Chris says, now so softly, so calmly, “show some respect.”

“I will,” the clerk says.

Then, just when both the clerk and viewers are breathing a sigh of relief, Christopher shoots the clerk.

“You motherfucker,” he shrieks. “You shot my foot.”

“It happens,” says Christopher, already on his way out the bakery door.

But that’s television, a scene from the first season of The Sopranos. In real life, Michael Imperioli, the actor who played mobster Chris is a thoughtful Tibetan Buddhist.

Buddhism can help an actor understand characters — to understand their point of view and motivations — and to develop compassion for them.

In an interview, I ask Imperioli how he reconciles his Buddhist beliefs about compassion with the violence in The Sopranos and other shows he’s been in. Hopefully, he tells me, “you’ll be revolted by it and you’ll realize it’s deluded to think that’s a justifiable way of living your life.” If you’re going to show a mob character, he continues, “it’s important to show him in a graphic way because otherwise, when you’re laughing with him and you see him with his wife, you’ll relate to him and maybe start to think something like ‘oh, he’s just another father.’ So you have to see that flip side—the cruelty and the dehumanizing of the victims—to realize who these people are and to realize that it’s a very destructive and unkind way of life. It’s more truthful to present both sides than to clean it up.”

Buddhism can help an actor understand characters — to understand their point of view and motivations — and to develop compassion for them. Imperioli says it’s important that he not judge the characters he plays as bad or evil because, once he does, he’s looking at them from an outside point of view. Bad and evil are labels, he says, “and have nothing to do with the internal mechanisms of what drives a character, which is what I’m going to need to get in touch with in order to play him. And, you know, even the worst people probably think they’re good in some ways. There’s something motivating them.”

Both real-life Michael Imperioli and fictional Christopher Moltisanti are screenwriters—Imperioli having written, among other things, several episodes of The Sopranos and having co-written Spike Lee’s The Summer of Sam. But Imperioli laughs when I ask in what other ways he’s similar to Christopher. “Not many, I hope,” he tells me. “I mean, Chris tried really hard. He tried hard to be good at what he did, both as a mobster and as a screenwriter. Not everybody who has an idea for a movie actually sits down and writes the script. He actually did it. He was diligent and I think I share that, but he had a lot of rough qualities. He was a very selfish person. I have been that at times, hopefully, though, less and less as I get older.”

Michael Imperioli, born in 1966, grew up in a working-class, Italian American neighborhood in Mount Vernon, New York. His father was a bus driver and amateur actor; his mother a secretary. The family was Catholic.

“I felt a connection to the teachings of Christ and the life of Christ,” Imperioli says, “but I really didn’t like going to church. Like most kids, I just felt bored.”

More to his childhood tastes were biblical movies — The Ten Commandments, King of Kings, The Greatest Story Ever Told. The message was compassion and love, Imperioli says, and he liked seeing these values promoted. It inspired him to see characters on the screen face obstacles and overcome them.

In his teens, Imperioli stopped going to church, and though he didn’t pursue it, he began to feel the draw of Buddhism. He was haunted by the images of Vietnamese monks setting themselves on fire in protest of the Vietnam War and he was fascinated by the work of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. But in high school, Imperioli was also reading plays and resolving to have an acting career, so—immersed in theater and film—a decade was to go by before he explored spirituality.

Imperioli read about mysticism and the occult; he read Krishnamurti and Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. The first Buddhist book he read was Meditation in Action, by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. “In my late twenties,” says Imperioli, “I was what Trungpa Rinpoche would call a spiritual shopper. I would read books and they would all make sense to me and I’d get a lot out of them. But a couple of days later, after I’d finished them, I’d be back in my old habitual patterns and habitual way of thinking. It wasn’t until I had a real practice, which I got through Buddhism, that I felt things starting to change.”

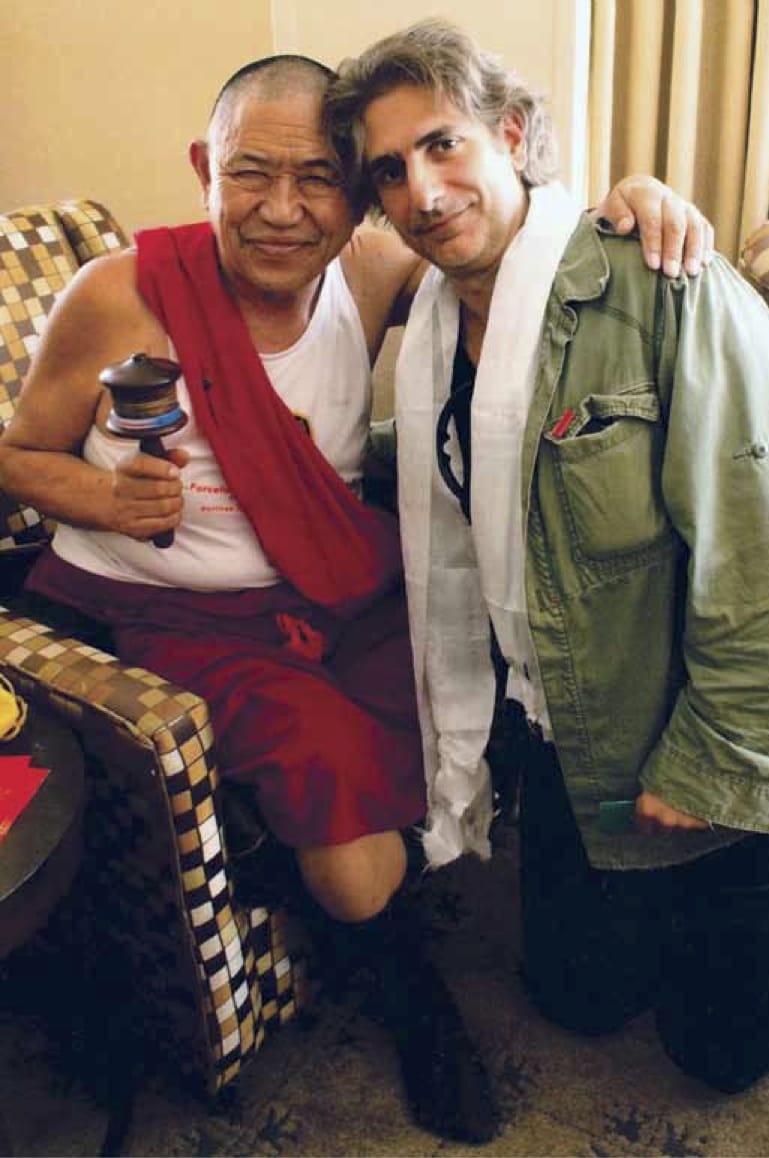

In 1996, Imperioli married Victoria Chlebowski, a stage designer who had fled her native Ukraine with her mother in 1976 because of anti-Semitism. In college, she studied some philosophy and read a lot of Buddhist books, which she shared with Imperioli. Then about five years ago, the couple began attending Buddhist teachings in New York City, where they live. The first teachings they went to were by Gelek Rinpoche, who has been the teacher of such luminaries as Allen Ginsberg and Phillip Glass. Now Imperioli and his wife go to all of Gelek Rinpoche’s teachings that they can manage, as well as to the teachings of Sogyal Rinpoche and the Dalai Lama. In July, they took refuge with Garchen Rinpoche.

“I always had a sense that spirituality meant having to work on yourself, rather than just adopting a set of beliefs and following them blindly,” says Imperioli. “And the more I learned about Buddhism, the more I felt that’s really what it is—direct methods of working on yourself, meditation being the first method. It made sense to me that the only way to transform your world was to transform yourself.”

Imperioli and his wife have busy careers and three children, yet they’ve made practice a priority by cutting out the superfluous. “We live a low-profile life,” Victoria Imperioli explains. “We have our circle of friends but we are very family-oriented. If we go to an event at all, we go to see someone’s play or film. We never really go to parties. You can’t fit in everything.”

“Buddhism has brought a lot of benefit to our family,” says Imperioli. “I see the change in my wife, because it’s easier to see it in someone else. Patience, tolerance, peace of mind—these things have increased in her a lot. When you can see your partner being more patient and being kinder to herself, it inspires you. Those benefits are for the children as well.”

And the more I learned about Buddhism, the more I felt that’s really what it is—direct methods of working on yourself, meditation being the first method. It made sense to me that the only way to transform your world was to transform yourself.

The couple practices meditation in the morning, as well as shortly before bed, and Imperioli says that he doesn’t find it difficult to fit practice into his schedule. The challenge is more procrastination. Sometimes he struggles to bring himself to the cushion or he struggles with runaway thoughts. At those times, he tells himself that it his conditioned mind and to let it go and just sit. “I don’t find practice ever to be easy, but that’s okay,” he says. “I can’t say that I’m a 100 percent—there are times when I don’t practice. I try to not let that happen too much and I try not to beat myself up about it when it does.”

Meditation has benefited not only Imperioli’s family life, but his work, specifically his concentration as an actor. “When you’re acting or preparing to act,” he says, “you want to focus your attention and block out distractions. It’s not the same thing as meditation but the focus has similarities.”

In an episode of the ABC crime drama Detroit 1-8-7, night has fallen and James Burke is in an apartment, holding his mother and children at gunpoint. Unarmed but wired, Detective Fitch, played by Imperioli, walks into the hostage scene.

“I know what it’s like,” says Fitch, with a whole SWAT team just outside the apartment, hanging on every word through the wire. “You love somebody so much. You don’t know why they caused you so much pain… that pain builds and builds… It’s like you’re a passenger. You’re in a car that’s speeding out of control but then you wake up and it’s you behind the wheel and it’s you who did these things. I did things… I hurt my wife. I hurt my kids. When I think about the things I’ve done, sometimes I really think it’d be easier just to end it… But I got these pictures on my wall. I see my kids—I can’t do it.”

Fitch pulls a photo out of his suit pocket. The smiling faces of Burke, his ex-wife whom he recently pumped full of bullets, and their two children. “These are your kids, James, your beautiful kids.”

Burke points his gun at Fitch. “Don’t come any closer.”

“Give me the gun, James.”

“Stop,” he chokes.

“I’m not gonna stop, James. Give me the gun.” Fitch takes the weapon; James sobs.

“God, forgive me,” says James.

Later that night, Fitch is back at the office with his new partner, Detective Washington, and they’re looking at a white board filled with murder cases. Washington’s voice is soft. “All that stuff you said… is it true?”

Fitch shoots him a hard look. “It was true when I said it.”

And that’s how it is with Michael Imperioli. On screen, when he says anything, it’s true. When he says it.

I ask Imperioli how he does it—how he manages to make his lines sound so real—even when he’s been repeating them take after take.

“You have to keep focusing on the elements of the scene and the objective of the character,” Imperioli says. “Every time you do the scene, you have to take in the reality of what you’re doing and be in the moment. The most important thing for an actor is to be in the moment.”

After finishing high school, Imperioli studied method acting in Manhattan at the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute. “The first thing they teach you is relaxation,” Imperioli tells me. “Basically, you sit in a chair and don’t really do anything. Then you might start adding sound or a physical movement.” You might work to recreate the physical sensations of holding an object, such as a pencil or a cup of tea. The idea is to focus on reliving the actual sensation, rather than simply miming what it looks like to hold the object. When Imperioli thinks back on his studies at Lee Strasberg, he sees a lot of similarities between the techniques he learned and Vajrayana Buddhist practice, with its visualizations and mantras.

“When I went to acting school,” says Imperioli, “I thought that in a couple of months I’d start working on TV and be making all kinds of money—I was that stupid. It was four years before I got a part in a play, which didn’t pay any money, and then another four years after that before I started making a living. If I had known how long it would take, I don’t know if I would have done it.”

While Imperioli waited for his break, he worked in restaurants; he was a waiter, busboy, bartender, and cook. Yeah, he believed he was going to make it. “But sometimes no,” he admits. “There are times when you feel like it just might never happen. The reality is that there are a lot of good actors and you don’t necessarily stand out that much. To succeed it takes a combination of being good and just persevering. Some luck doesn’t hurt either.” That said, according to Imperioli, it’s not luck that someone gives you a part. It’s luck that you don’t get hit by a bus or get cancer, and that luck enables you to stick it out—if you have the perseverance in you. Eventually, he says, after you’ve done twenty plays and you’ve done a good job, someone knows you and gives you a small part in a film.

Michael Imperioli’s first film credit is for John G. Avildsen’s Lean on Me. After that, he landed other small parts in a variety of flicks, including Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever and Malcolm X, Scott Kalvert’s The Basketball Diaries, and Mary Harron’s I Shot Andy Warhol. Then, in 1999, he got the part of Christopher Moltisanti in The Sopranos, the role he continues to be most well known for and for which, in 2004, he won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series.

For years, here and there, people on the street had recognized Imperioli and come up to talk to him, but The Sopranos took it up a notch—a big notch. “To be honest,” he says, “it was a bit of an adjustment. When your privacy is invaded to a much bigger degree, it’s a little strange trying to navigate that.”

Suddenly finding himself in the limelight was one of the reasons that Imperioli ended up delving into Buddhism. “In my twenties, pretty much all I cared about was acting,” he explains. “I was driven to succeed, which you have to be to make it in the business.” But what happened to Imperioli is what happens to a lot of people. “Finally, on some level,” he says, “you achieve what’s considered success. Then you realize it doesn’t necessarily make you happy. So, if what you thought was going to be the ultimate thing to fulfill you doesn’t actually make you happy, you better figure out what does.”

“How can a path all about improving the self be about selflessness?”

Gus asks Lisette this question over a drink, his tone taking a sharp turn away from flirtation. They’d just met earlier in the evening, while she was outside having a smoke and he was ranting his poems into his cellphone. Now Gus presses on: “If I’m concerned with my life, my karma, my rebirth… where’s the sacredness in that?”

His anger jars against the bar’s mellow music, the plaintive strains of guitar.

“What are you crying for?” he sneers. “You’re crying ’cause you fear suffering. It’s all about you. It’s all about nothing.”

“It’s not,” says Lisette. “The soul is not nothing.”

“The truth is, sweetheart, there is no soul… It’s all up here.” Gus strokes her head.

“Then what? We’re all just… bodies?”

Gus smiles. “It’s the body, which is immortal. Now we’re human and it’s rotted into worms, which are eaten by birds, which are eaten by cats, which are eaten by dogs, who shit us out and we become grass, which is then eaten by cows who are milked and churned into cheese and swallowed in a cheeseburger by some teenager down at McDonald’s and, hey, we’re human once more, and on and on… We’re immortal.”

Lisette weeps and Gus kisses her cheeks, cups her face in his hands. “Do you see the beauty in that?” he murmurs.

She nods weakly.

“Yes?” he persists, and she nods again. Then he traces her mouth with his thumb and slips the whole thing inside.

“Do you see the beauty in that?”

She sucks on one of his fingers. Then a second. A third. A fourth—her whole mouth stuffed. And still hungry.

Gus isn’t played by Imperioli, rather Gus is his creation—a character from the 2009 film Hungry Ghosts, which was written and directed by Imperioli and produced by his wife. The title, which borrows from Buddhist cosmology, refers to beings with tiny mouths and huge, hungry stomachs; they try to consume but swallowing is excruciating and they can’t get enough down their throats to satisfy. The film uses the term as a metaphor to describe people with a deep feeling of emptiness who try to fill themselves up by chasing their endless, illusory appetites—drugs, alcohol, sex, validation, sensation.

Imperioli wrote the script shortly after he started going to Buddhist teachings, yet the film is not Buddhist and neither are the characters in it, not even the guru character. Her spirituality is what Imperioli describes as a “hodgepodge,” mostly a mix of Buddhism and Hinduism. “There are a lot of spiritual ideas that come into Hungry Ghosts,” he says, “but it’s really about spiritual confusion. It’s about searching and not knowing what to search for, knowing you want something but not knowing what it is. I was inspired to write about those things from pursuing a spiritual path.

“I spent several years knowing that I had to start meditating but not doing it,” says Imperioli. “I was convinced I couldn’t.”

Like many people, he believed that in order to meditate he had to stop thinking and he knew he wouldn’t be able to do that. Eventually, however, he came to realize his misconception. What meditation actually involves is sitting down and acknowledging your thoughts.

Hungry Ghosts wraps up with meditation. That is, in the final scene, many of the principal characters meditate together, and right after Imperioli finished making the film, he started meditating himself. “So it’s not a movie about Buddhism,” he explains, “but in some ways it led to it.”

Masters meditating in caves thousands of years ago had insights that scientists are only now coming to terms with. The interrelation between physical science and Buddhism could help our view of the world.

Imperioli and his wife are working on a new film with a spiritual bent; they are executive producers of a documentary about the Tenzin Gyatso Scholars Program. This program, which sponsors Tibetan monastics to study neuroscience, biology, physics, and the social sciences in the United States, is a project of the Tenzin Gyatso Institute. Founded in 2007 by Sogyal Rinpoche, the institute strives to advance the Dalai Lama’s vision and values, and the Scholars Program goes right to the heart of this mission. The Dalai Lama has frequently stated that science has enriched his views and that Tibetan religious education would benefit from a thorough understanding of how Western thought and inquiry has developed.

At the same time, says Imperioli, “masters meditating in caves thousands of years ago had insights that scientists are only now coming to terms with. The interrelation between physical science and Buddhism could help our view of the world.”

When Imperioli tells me this, I think again of the characters in Hungry Ghosts and their search for meaning and happiness. In particular, I think of Gus and his raging question: “How can a path that is all about improving the self be about selflessness?” I ask Imperioli how he’d answer that.

“Gus is seeing that it’s all about the self,” says Imperioli. “He failed to make the leap toward making it really be about compassion and that’s where he was limited.”

Compassion and the importance of it is what Imperioli wants to leave his viewers with. “Compassion and the possibility of transformation,” he says. “You can wake up.”

I smile into the phone. Michael Imperioli’s voice sounds just like Christopher Moltisanti’s, but his words don’t. Not at all.