Gender inequality is difficult to rationalize in a tradition that supposedly proclaims enlightenment for all. When questioned by his faithful attendant Ananda, the Buddha assured him that women have equal potential to achieve the fruits of the path, including liberation, the ultimate realization. This definitive statement should have been sufficient to clear the path for women’s equality, but social realities rarely match theoretical ideals.

Even though countless women have reportedly achieved the ultimate goal of liberation—becoming arhats—women’s status has consistently been subordinate in Buddhist societies. Being born male automatically elevates a boy to first-class status, while being born female universally relegates a girl to second-class status. Wealth, aristocratic birth, or opportune marriage may mitigate the circumstances, but the general pattern of social status remains in full view. Although Buddhist societies may have overall been more gender egalitarian than many others, stark gender discrimination persists even today.

Nowhere is the subordination of women more evident than in the Buddhist sangha, the monastic community. After some hesitation, possibly based on his concern for women’s safety, the Buddha gave women the opportunity to live a renunciant lifestyle. According to the story, however, it was not on equal terms with the monks. It is taught that the Buddha’s foster mother Mahapajapati, who became the first bhikkhuni, or fully ordained nun, was required to observe eight weighty rules that continue to this day to make the nuns dependent upon the monks.

Although the language of the texts shows that these passages were added much later, nuns’ subordinate status, and a prediction that the nuns’ admission would decrease the lifespan of the Buddha’s teachings, have contributed to the perception of women’s inferiority. The teachings have far outlived the prediction (which was adjusted over time!), but the misconception has endured.

The situation of nuns today varies by tradition. In the Theravada traditions of South and Southeast Asia, the lineage of full ordination for women came to an end around the eleventh century, and many followers believe that it cannot be revived. Women who renounce household life observe eight, nine, or ten precepts, including celibacy, yet they are not considered part of the monastic sangha. Until recently they received far less education and support than monks.

In the Mahayana traditions of East Asia, the bhikkhuni lineage of full ordination was brought from Sri Lanka to China in the fifth century and flourishes today in China, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Chinese diaspora. In these traditions, nuns are well supported by the lay community and have opportunities for education roughly equal to the monks.

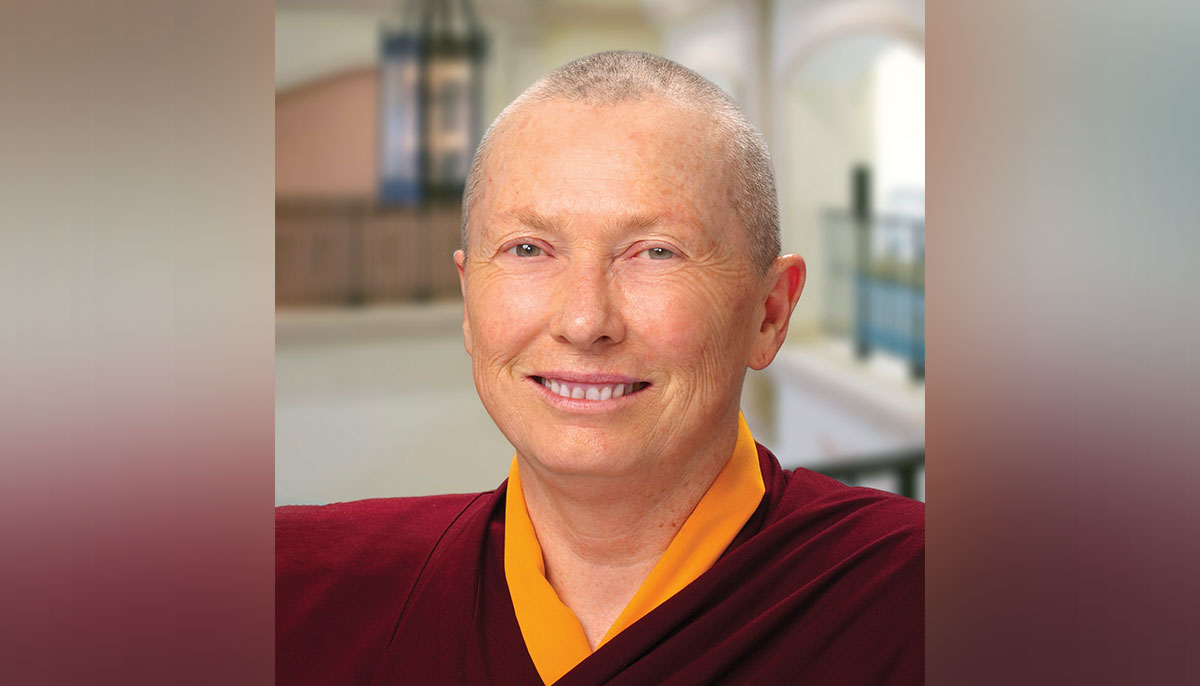

The bhikkhuni lineage was never established in the Vajrayana tradition of Inner Asia, but women may receive novice ordination from monks and are considered part of the monastic sangha. In the last three decades, nuns have worked hard to improve their living conditions and educational opportunities. Many of them hope that the Dalai Lama will find a way to establish a lineage of full ordination for women in the Tibetan tradition.

Ideas about how to redress the gender imbalance, both for monastics and lay women, widely differ depending on the situation. For those Buddhist women in remote areas of Asia, better nutrition, health care, and education are top priority, while for those in urban areas the concerns are about gender parity in juggling work, family, and practice. Women everywhere are oppressed by sexual harassment and unequal representation.

Many Buddhists feel that it is time to take a fresh look at how Buddhist texts and teachings address gender. With the Buddha’s declaration of women’s equal potential for liberation, things started off very well. After his passing, however, patterns of male domination again became the norm in Buddhist societies. The plot thickened about five centuries after the Buddha’s passing, with the appearance of the Perfection of Wisdom (Prajnaparamita) texts. These texts replace liberation from cyclic existence with the perfect awakening of a buddha as the goal of the path—a quantum leap in commitment that requires the aspirant (bodhisattva) to accumulate merit and wisdom for three countless eons.

Among the thirty-two “special marks” of a buddha, the most surprising to many modern Buddhists is a sheathed penis “like a horse.” This mark has been taken to mean that a fully awakened buddha is necessarily male. Exactly what the advantage of such an appendage might be is unclear, especially alongside other fantastic marks such as a spiral between the eyebrows that stretches for legions.

Are buddhas shown with male genitalia because men are presumed to be superior to women? Does the mark verify that the buddhas are sexual beings who have sublimated sexual desire? Are men more apt than women to achieve the fully awakened state because they must work harder to overcome sexual desire? Or is the presumption of maleness simply another patriarchal move to maintain superiority?

In addition to taking a fresh look at Buddhist texts and teachings, it is time to reexamine Buddhist institutions, which are almost all completely under male leadership, and reassess Buddhist social realities. Rather than blithely swallowing the meme that everyone is equal in Buddhism, or naively believing that gender is irrelevant to awakening, Buddhists need to reevaluate the way women are treated.

For example, even today in the Tibetan tradition a three-year-old boy can be honored with the title “Lama” (meaning “guru”), whereas a highly educated seventy-year-old nun is typically demeaned with the title “Ani” (meaning “auntie”). Donations—even by women and even in supposedly enlightened Western societies—are routinely channeled primarily to male teachers and monks’ monasteries. Discriminatory attitudes have become unconsciously internalized by people in ways that are damaging to both themselves and others.

Buddhists today need to wake up to this fact and transform their habitual tendencies, equally embracing all beings with compassion. In the Buddhist traditions, the ultimate concern for women, especially nuns, is awakening—either the achievement of liberation from cyclic existence or the perfect awakening of a buddha. The fact that women are now working to achieve full representation in the Buddhist traditions and are openly voicing their aspirations reflects their compassionate concern for the well-being of all sentient life.