I have two dear friends who married, and then had a child, a lovely boy. They gave him my name for a middle name, so, I was particularly happy on top of the happy I’d already felt for them.

When their child was about three, out came a proclamation: “I’m a girl.”

Actually, the child had been saying things like that for a long time, but it can be hard to hear what you’re not expecting. Once their attention was turned toward what was said, they realized how long their child had been expressing this sense of identity.

In a letter they wrote to family and friends, they told us that, at first, “We took it as imaginative play, no different than pretending to be a dinosaur or a bear.” However, it continued, over and over: “I am a girl.” And, “I want to be a woman when I grow up.” Something important was going on.

In fact, something important has been going on for all of us, as the issue of transgender identity has exploded within our culture. I believe it follows closely upon the powerful assertion of full equality and basic humanity by women, and then by gay, lesbian, and bisexual people claiming their place. As best I can see, this is a powerful moment on our march to a healthier and more just world.

Of course, all this can be confusing. But in the midst of their confusion, my friends made what I feel is the only appropriate response: they gave their child a girl’s name. They began to dress her as a girl. And they have asked all of us who love them to use that name and use female pronouns whenever referring to their daughter.

My friends now report of their daughter that she exhibits “joy at her new name and her new clothes, her delight in being seen as a girl.”

The loss of that middle name is a tiny sadness for me, but the knowledge that their daughter is being given a chance toward a fully integrated life is a great joy. A totally fair exchange. And it’s paid off. My friends now report of their daughter that she exhibits “joy at her new name and her new clothes, her delight in being seen as a girl.” And there’s been “the lessening of tantrums, with her becoming more relaxed and more affectionate.”

They also acknowledge that they don’t know what the future holds. But they’re committed to meeting it all with open hearts and with the clearest thinking they can bring to the matter, which, it turns out, is substantial.

Along the way, and in the gentlest possible manner, they’ve helped educate their gang about the issues of transgender identity, providing a small reading list and skillfully explaining the difference between sexual orientation and gender identity. (The first is about who you go to bed with, the other who you go to bed as.) This is not about sexualizing anything; it is about fully accepting a person as a person.

While I believe this anecdote speaks mostly to who my friends are as human beings, it can’t be missed that they are, also, dedicated practitioners of the Zen way. I find it impossible to believe that their years on the meditation cushion — looking deeply into their own hearts and minds, and living among others who share that same fierce commitment — could have been anything but a positive when the proverbial rubber hit the road.

There is a wonderful koan, collected in The Blue Cliff Record as case 89:

Yunyan asked Daowu, “‘How does the Bodhisattva Guanyin use those many hands and eyes?”’

Daowu answered, “‘It is like someone in the middle of the night reaching behind her head for the pillow.”’

Yunyan said, “I understand.”

Daowu asked, “How do you understand it?”

Yunyan said, “‘All over the body are hands and eyes.”

Daowu said, “That is very well expressed, but it is only eight-tenths of the answer.”

Yunyan said, “How would you say it, Elder Brother?”

Daowu said, “Throughout the body are hands and eyes.”

Both Yunyan and Daowu were students of the same teacher and would themselves each become famous teachers. The peculiar mix of myth and history that is Zen’s lineage tradition tells me that Yunyan is my teacher’s teacher’s teacher in an unbroken line running from my life back to the beginning of the ninth century. And according to some records, they were actually brothers, but for various reasons this seems unlikely.

Whatever the case, the important thing for us here is that both these monks had their ideas of self and other collapse and then saw deeply into authentic interconnectedness. Not unlike my friends when their child told them she was their daughter.

Daowu, at the time this story takes place, perhaps saw a bit deeper than his dharma brother. Although perhaps not. Perhaps he was playing. In the Zen way, we play a lot, each of us taking different parts in turn. Play is an important part of the path. That noted, in this conversation we get a sense of what it means to move from thinking of the interdependent web as a really good idea, to realizing that it describes who we actually are. My friends and their daughter are perfect examples of what this might look like.

I saw a photograph at the Brooklyn Zen Center, one of those panoramic shots of a line of Zen meditation pillows. From the left there are a number of people sitting in the traditional Soto Zen way, facing away from the camera and toward the wall. Then there is an empty pillow or two, and then sitting on the next several pillows are children, playing. This is what Zen is supposed to be: alive, multifaceted. It is the manifestation of Guanyin.

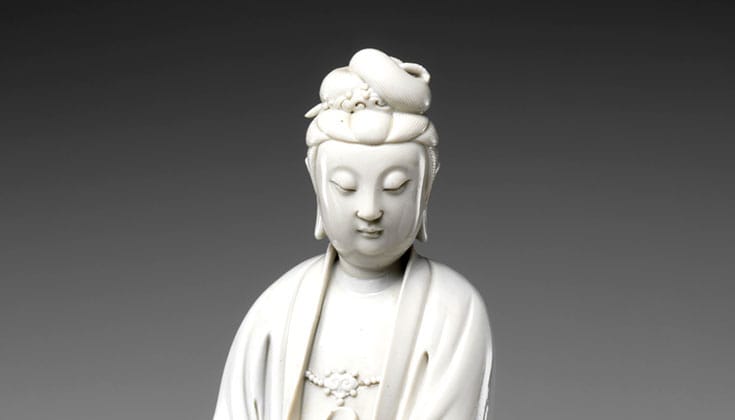

Guanyin, the archetype of compassion, is sometimes portrayed as a man, sometimes as a woman, sometimes in androgynous form. Always, though, Guan Yin represents the deeply, profoundly felt impulse to reach out. This reaching out is the body itself, awakening.

Guanyin, the archetype of compassion, is sometimes portrayed as a man, sometimes as a woman, sometimes in androgynous form. Always, though, Guan Yin represents the deeply, profoundly felt impulse to reach out. This reaching out is the body itself, awakening. And, Daowu says of this need to act, it comes naturally. Not through an interpretation of the image of the interdependent web, not through reading The Wealth of Nations, not through solid Marxist analysis, not through an investigation of Mary’s hymn in the Gospel According to Luke, but rather like someone turning in her sleep and reaching a hand behind her head to adjust her pillow.

Or, if you will, like concerned parents asking that their child be addressed and referred to using pronouns appropriate to her sense of gender identity. Or like people sitting in zazen, their children playing at the end of the line. Just this. Ends and means, one thing. Our interdependence, and you and me—it’s all one thing.

So, Yunyan’s “eight tenths of an answer” is that this realization is like having eyes and hands all over our bodies. True, true, says his brother, but one hundred percent is that those eyes and hands are our body. There is no separation, however slight, and the universal comes to be known in the only place it can be known: in each particular instance, in each particular person, in this particular permutation of the great mess.

An old Zen saying has it that even the Buddha is continuing to practice. So our practice continues, too. It’s a practice of refinement, the path becoming one of ever-increasing intimacy, and each of us coming to know the other as we all walk the great way together, constantly transformed and transforming.