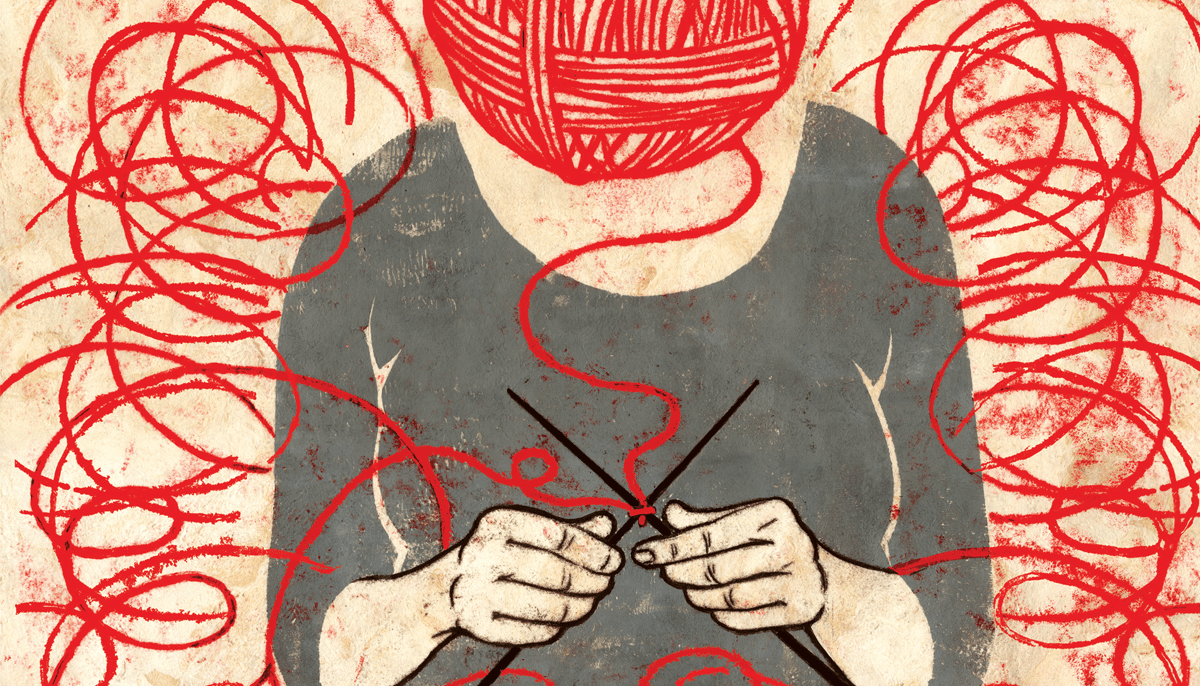

I started knitting well before I found a steady Zen practice. In fact, I feel that knitting set me up well for Zen. Well, maybe not for studying the philosophy of Dogen, but for zazen meditation anyway.

Knitting is slow art. Zen is slow training. In Zen, emphasis is placed on the act of sitting rather than enlightenment, the end goal. In knitting, I can also place emphasis on the activity rather than the final product. While a finished knitted object is often (though not always!) something that brings a lot of joy, when my attention is placed on the process of creation rather than the final sweater or scarf, the experience is that much richer.

Here are five ways that I’ve found my knitting practice—or any creative process—to be an extension of my Zen practice.

1. Find the Right Posture and Intention

My knitting bag is like a portable zafu. Inside are yarn and needles and a universe of possibilities. These creative tools—simple items made from bamboo and wool—have the same grounding quality as my meditation cushion. Taking the needles and yarn in hand, feeling the familiar warmth of each, is a reconnection, much like finding one’s seat on the cushion. It’s a welcoming home.

With needles in hands, my intention is set: I will use these tools to loop and knot in such a way that something useful is created, be it a hat, sweater, blanket, or toy. With the space created and intention set, I remain open to what comes. And what comes is constantly changing—stitch by stitch, row by row. In the dharma of knitting, there is no past, no present, no future, only change.

2. Concentrate on the Activity

The stitches start to flow as easy as breath. A rhythm is created. Insert needle, loop yarn, pull through. Insert needle, loop yarn, pull through. Loop after loop, knot after knot: fabric is created.

Both paths—Zen and knitting—offer opportunities for noticing the mind and returning to the action.

Sometimes my mind stays with the action and sometimes my mind wanders. As with any activity, I can approach knitting with careful attention or with carelessness. The practice is to come back to the action—insert needle, loop yarn, pull through; breathe in, breathe out—without holding on to the promise of the finished object. With an easy stitch pattern, like garter or stockinette, my mind is more prone to wandering. Lace knitting, however, requires that I really pay attention to the complicated stitch pattern if it’s to look harmonious and purposeful in the end. Both paths—Zen and knitting—offer opportunities for noticing the mind and returning to the action.

3. Allow the Ten Thousand Things to Come Forward

When my mind quiets and my attention is on my hands, needles, and yarn, the world opens. Soft sound of needles clicking. Smooth feel of wool. Color, texture, light. Perhaps a birdsong, or music, or conversation. All things feel present and connected. There is no thinking of outcome. This is the feeling of wholeheartedness. This is the feeling of worthwhile activity. There is no me, no other. There is just an open meeting place where all things come together.

4. Let Go of Expectations

Often when a sense of expansiveness arrives, I make a mistake and come back to the small view. Knitting is filled with opportunities to fail, make mistakes, face disappointment. Dropped stitches, wrong gauges, missed pattern repeats. Knitting is a slow craft, and when mistakes come up they can be slow to fix. Tearing out hundreds of stitches. Starting over. When something wrong comes up, it’s a ripe time to practice nonattachment, letting go of expectations.

This is when the vow of practicing with kind intention is most important. Why knit when it’s easier and cheaper to buy what is needed? I knit because it is a joyful and wholesome activity. Mistakes are an opportunity to be reminded that it’s about the activity and not the finished object.

This is a kind of vow. In Zen, we vow to save all sentient beings. That is a big vow, an endless vow. In my knitting, I can vow to bring joyful presence to my activity and bring joy to others through the things I make. That is a smaller vow, yet it is still endless, and I like to think it’s good practice for the bigger vow of saving all sentient beings.

5.Allow for a Connection to All Things to Arise

It’s hard not to talk about connection to all things when talking about knitting. Knitted fabric is essentially a small representation of Indra’s Net. Each stitch is connected to the next and essential to the creation of the whole. These stitches remind us of the connectedness of all things: the sheep, shepherd, and hillside from which the wool is sourced; the shearer, miller, and dyer who transform the wool to yarn; the local yarn shop and knit designers who make the yarn available and inspire its potential—all are present in a single skein. And with our hands, we take the next step to create an object to use or give. In this way, in a small and connected economy, knitting is a radical act. Knitting is a way to connect with the world and our communities—and ourselves.