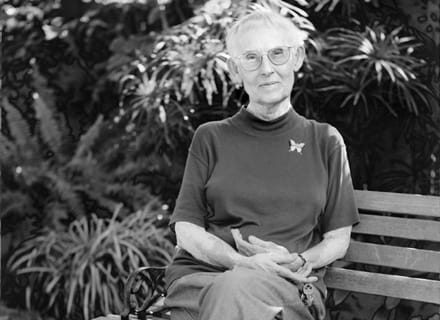

In this teaching, the late American Zen pioneer Charlotte Joko Beck reminds us that having a sane and satisfying life comes from having a sane and balanced practice.

My dog doesn’t worry about the meaning of life. She may worry if she doesn’t get her breakfast, but she doesn’t sit around worrying about whether she will get fulfilled or liberated or enlightened. As long as she gets some food and a little affection, her life is fine. But we human beings are not like dogs. We have self-centered minds which get us into plenty of trouble. If we do not come to understand the error in the way we think, our self-awareness, which is our greatest blessing, is also our downfall.

To some degree we all find life difficult, perplexing, and oppressive. Even when it goes well, as it may for a time, we worry that it probably won’t keep on that way. Depending on our personal history, we arrive at adulthood with very mixed feelings about this life. If I were to tell you that your life is already perfect, whole, and complete just as it is, you would think I was crazy. Nobody believes his or her life is perfect. And yet there is something within each of us that basically knows we are boundless, limitless. We are caught in the contradiction of finding life a rather perplexing puzzle, which causes us a lot of misery, and at the same time being dimly aware of the boundless, limitless nature of life. So we begin looking for an answer to the puzzle.

The first way of looking is to seek a solution outside ourselves. At first this may be on a very ordinary level. There are many people in the world who feel that if only they had a bigger car, a nicer house, better vacations a more understanding boss, or a more interesting partner, then their life would work. We all go through that one. Slowly we wear out most of our “if onlies.” “If only I had this, or that, then my life would work.” Not one of us isn’t, to some degree, still wearing out our “if onlies.” First of all we wear out those on the gross levels. Then we shift our search to more subtle levels. Finally, in looking for the thing outside of ourselves that we hope is going to complete us, we turn to a spiritual discipline. Unfortunately we tend to bring into this new search the same orientation as before. Most people who come to the Zen Center don’t think a Cadillac will do it, but they think that enlightenment will. Now they’ve got a new cookie, a new “if only.” “If only I could understand what realization is all about, I would be happy.” “If only I could have at least a little enlightenment experience, I would be happy.” Coming into a practice like Zen, we bring our usual notions that we are going to get somewhere—become enlightened—and get all the cookies that have eluded us in the past.

Our whole life consists of this little subject looking outside itself for an object. But if you take something that is limited, like body and mind, and look for something outside it, that something becomes an object and must be limited too. So you have something limited looking for something limited and you just end up with more of the same folly that has made you miserable.

We have all spent many years building up a conditioned view of life. There is “me” and there is this “thing” out there that is either hurting me or pleasing me. We tend to run our whole life trying to avoid all that hurts or displeases us, noticing the objects, people, or situations that we think will give us pain or pleasure, avoiding one and pursuing the other. Without exception, we all do this. We remain separate from our life—looking at it, analyzing it, judging it, seeking to answer the questions, “What am I going to get out of it? Is it going to give me pleasure or comfort or should I run away from it?” We do this from morning until night. Underneath our nice, friendly facades there is great unease. If I were to scratch below the surface of anyone I would find fear, pain, and anxiety running amok. We all have ways to cover them up. We overeat, overdrink, overwork; we watch too much television. We are always doing something to cover up our basic existential anxiety. Some people live that way until the day they die. As the years go by, it gets worse and worse. What might not look so bad when you are twenty-five looks awful by the time you are fifty. We all know people who might as well be dead; they have so contracted into their limited viewpoints that it is as painful for those around them as it is for themselves. The flexibility and joy and flow of life are gone. And that rather grim possibility faces all of us, unless we wake up to the fact that we need to work with our life, we need to practice. We have to see through the mirage that there is an “I” separate from “that.” Our practice is to close the gap. Only in that instant when we and the object become one can we see what our life is.

Enlightenment is not something you achieve. It is the absence of something. All your life you have been going forward after something, pursuing some goal. Enlightenment is dropping all that. But to talk about it is of little use. The practice has to be done by each individual. There is no substitute. We can read about it until we are a thousand years old and it won’t do a thing for us. We all have to practice, and we have to practice with all of our might for the rest of our lives.

What we really want is a natural life. Our lives are so unnatural that to do a practice like Zen is, in the beginning, extremely difficult. But once we begin to get a glimmer that the problem in life is not outside ourselves, we have begun to walk down this path. Once that awakening starts, once we begin to see that life can be more open and joyful than we had ever thought possible, we want to practice.

We enter a discipline like Zen practice so that we can learn to live in a sane way. Zen is almost a thousand years old and the kinks have been worked out of it; while it is not easy, it is not insane. It is down to earth and very practical. It is about our daily life. It is about working better in the office, raising our kids better, and having better relationships. Having a more sane and satisfying life must come out of a sane, balanced practice. What we want to do is find some way of working with the basic insanity that exists because of our blindness.

It takes courage to sit well. Zen is not a discipline for everyone. We have to be willing to do something that is not easy. If we do it with patience and perseverance, with the guidance of a good teacher, then gradually our life settles down, becomes more balanced. Our emotions are not quite as domineering. As we sit, we find that the primary thing we must work with is our busy, chaotic mind. We are all caught up in frantic thinking, and the problem in practice is to begin to bring that thinking into clarity and balance. When the mind becomes clear and balanced and is no longer caught by objects, there can be an opening—and for a second we can realize who we really are.

But sitting is not something that we do for a year or two with the idea of mastering it. Sitting is something we do for a lifetime. There is no end to the opening up that is possible for a human being. Eventually we see that we are the limitless, boundless ground of the universe. Our job for the rest of our life is to open up into that immensity and to express it. Having more and more contact with this reality always brings compassion for others and changes our daily life. We live differently, work differently, relate to people differently. Zen is a lifelong study. It isn’t just sitting on a cushion for thirty of forty minutes a day. Our whole life becomes practice, twenty-four hours a day.

I’m often accused of emphasizing the difficulties in practice. The accusation is true. Believe me, the difficulties are there. If we don’t recognize them and why they arise, we tend to fool ourselves. Still, the ultimate reality—not only in sitting, but also in our lives—is joy. By joy I don’t mean happiness; they’re not the same. Happiness has an opposite; joy does not. As long as we seek happiness, we’re going to have unhappiness, because we always swing from one pole to the other.

From time to time, we do experience joy. It can arise accidentally or in the course of our sitting or elsewhere in our lives. For a while after sesshin, we may experience joy. Over years of practice, our experience of joy deepens—if, that is, we understand practice and are willing to do it. Most people are not.

Joy isn’t something we have to find. Joy is who we are if we’re not preoccupied with something else. When we try to find joy, we are simply adding a thought—and an unhelpful one, at that—onto the basic fact of what we are. We don’t need to go looking for joy. But we do need to do something. The question is, what? Our lives don’t feel joyful, and we keep trying to find a remedy.

Our lives are basically about perception. By perception I mean whatever the senses bring in. We see, we hear, we touch, we smell, and so on. That’s what life really is. Most of the time, however, we substitute another activity for perception; we cover it over with something else, which I’ll call evaluation. By evaluation, I don’t mean an objective, dispassionate analysis—as, for example, when we look over a messy room and consider or evaluate how to clean it up. The evaluation I have in mind is ego centered: “Is this next episode in my life going to bring me something I like, or not? Is it going to hurt, or isn’t it? Is it pleasant or unpleasant? Does it make me important or unimportant? Does it give me something material?” It’s our nature to evaluate in this way. To the extent that we give ourselves over to evaluation of this kind, joy will be missing from our lives.

It’s amazing how quickly we can switch into evaluation. Perhaps we’re functioning pretty well—and then suddenly somebody criticizes what we’re doing. In a fraction of a second, we jump into our thoughts. We’re quite willing to get into that interesting space of judging others or ourselves. There’s a lot of drama in all of this, and we like it, more than we realize. Unless the drama becomes lengthy and punishing, we enter willingly into it, because as human beings we have a basic orientation toward drama. From an ordinary point of view, to be in a world of pure perception is pretty dull.

Suppose we’ve been away on vacation for a week, and we come back. Perhaps we’ve enjoyed ourselves, or we think we have. When we return to work, the “In” box is loaded with things to do, and scattered all over the desk are little messages, “While You Were Out.” When people call us at work, it usually means that they want something. Perhaps the job we left for someone else to take care of has been neglected. Immediately, we’re evaluating the situation. “Who fouled up?” “Who slacked off?” “Why is she calling? I bet it’s the same old problem.” “It’s their responsibility anyway. Why are they calling me?” Likewise, at the end of sesshin we may experience the flow of a joyful life; then we wonder where it goes. Though it doesn’t go anywhere, something has happened: a cloud covers the clarity.

Until we know that joy is exactly what’s happening, minus our opinion of it, we’re going to have only a small amount of joy. When we stay with perception rather than getting lost in evaluation, however, joy can be the person who didn’t do the job while we were gone. It can be the interesting encounter on the phone with all of the people we have to call, no matter what they want. Joy can be having a sore throat; it can be getting laid off; it can be unexpectedly having to work overtime. It can be having to take a math exam or dealing with one’s former spouse who wants more money. Usually we don’t think that these things are joy.

Practice is about dealing with suffering. It’s not that the suffering is important or valuable in itself, but that suffering is our teacher. It’s the other side of life, and until we can see all of life, there’s not going to be any joy. To be honest, sesshin is controlled suffering. We get a chance to face our suffering in a practice situation. As we sit, all the traditional attributes of a good Zen student come under fire: endurance, humility, patience, compassion. These things sound great in books, but they’re not so attractive when we’re hurting. That’s why sesshin ought not to be easy: we need to learn to be with our suffering and still act appropriately. When we learn to be with our experience, whatever it is, we are more aware of the joy that is our life.

© Everyday Zen (1989) and Nothing Special (1993), by Charlotte Joko Beck, reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.