To practice with anger—rather than simply being a victim of it—is to make the effort to respect and understand it. This involves being willing to look more deeply at the complex of negative emotions, which naturally arise as part of our human condition. It requires that we take responsibility for these emotions so we can begin to do something creative with them.

Buddhism is justly valued for its many effective and sensible ways of working with anger. All these ways depend on basic mindfulness, the ability to create the inner space necessary to investigate and be fully present with an emotion. h2 emotions, especially negative ones like greed, anger, jealously, and so on, spin us around. Mindfulness gives us a chance to be present with an emotion before we start spinning or even while we are spinning. Rather than being propelled and likely blinded by what we think we want, we are present and willing to see more widely and openly what is actually happening. Such seeing changes what we experience, how we behave, and, ultimately, the sorts of things that happen to us.

In addition, Buddhism offers more intentional, active practices that support and are supported by mindfulness. In recent years, I have been practicing the lojong, or “mind training,” teachings of Tibet. This is a collection of practices to transform negative emotions into sympathy, love, and compassion.

The most famous of all the lojong texts, The Root Text of the Seven Points of Training the Mind, is based on a list of fifty-nine practice slogans. These slogans are memorable, often humorous aphorisms that point us in an advantageous spiritual direction.

My Zen-inflected method of working with a slogan is to copy it again and again in a notebook and repeat it to myself silently during meditation. I stay with the slogan until all my ideas about it become boring and there is only the slogan itself, like a good wise friend, urging me on. When you practice like this, the slogan will start to pop into your mind unbidden, a substitute for the many other mindless thoughts that otherwise would be popping up. And every time it does, it reminds you of your practice and of the necessity of working with your emotions not just when you’re meditating and feeling spiritual but all the time, especially in the midst of problems.

I’d like to discuss five lojong slogans and how they can be helpful in working with anger.

Don’t Figure Others Out

Think of how much we all talk about our friends and relatives, analyzing their words and deeds, sizing them up as if we actually knew what made them tick. But just as you don’t appreciate being reduced to this or that cartoonish, likely uncomplimentary, version of yourself, neither do they.

The fact is, any version of who you, they, or anyone else is, is incorrect. Sitting on your meditation cushion for half an hour is long enough to show you quite directly that you are full of contradictions, unacknowledged issues, and unfinished business. There are so many good and bad sides to you that it would be hard to precisely define your character. And others are just like you, which means no one has the capacity to figure others out. And yet we do figure them out—or think we do. Then, based on that mischaracterization, we react.

We are angry at a phantom, a figment of our own imagination.

We do this especially with someone we are angry at. We know exactly who this person is, why he or she is unworthy of our regard and richly worthy of our anger. Why would we give this terrible person the benefit of the doubt? Never!

Yet the truth is that we have no idea what is going on inside this person. We have no idea what really makes him or her tick. We are angry at a phantom, a figment of our own imagination. Don’t figure others out.

Work With Your Biggest Problems First

Working with our biggest problems first is the opposite of what we want to do. Usually we prefer to take on something easy and work our way up to the tough things, but operating like this we never seem to get to that tough stuff.

This slogan says turn first toward what is really difficult. Screw up your courage and go there right away. This will take all the mindfulness you have been able to cultivate from your time on the meditation cushion—and more. It will also take forbearance, one of the most powerful and least appreciated of all spiritual practices. Forbearance is the capacity to patiently stay with something unpleasant or difficult and face it rather than to do what comes naturally, which is to turn away. Forbearance requires that we develop the capacity—in our body, in our breath, in our heart—to stand firm and aware without acting, at least for the moment.

When we’re angry, we typically blame and lash out. Most of us are not courageous enough to lash out at the people we are actually angry at, so instead we lash out at someone else who is safer, take potshots, gossip, or just grouse and feel indignant in the privacy of our own minds. Yet these activities probably don’t hurt the target of our anger at all. They do, though, hurt us and other people plenty.

Working with the biggest problems first means that when we’re angry, we turn toward the anger. Instead of leaping to blame, recrimination, or distraction, we feel the anger in our body, in our breathing, in our racing thoughts. When we practice like this, we will calm down, see more of what is actually going on, and, eventually, be able to act wisely.

Abandon Hope

What! Don’t we want to be hopeful? Don’t we want to hope that tomorrow will be better than today? That our spiritual endeavors will pay off? That our anger will transform?

In a word, no, we don’t. If you investigate hope, you’ll see how counterproductive it can be. To hope usually means to reject the experience of this moment, and, therefore, hope can be a kind of cowardice. Rather than face what’s going on right now, we focus our attention on later, when things will hopefully be much more pleasant than they are at the moment.

In the case of anger, maybe we have some hope that, internally, the anger will somehow dissolve or that, externally, the person we are angry at will see the error of his or her ways and finally apologize and make amends. Or maybe we are hoping that if we do our Buddhist practice, everything will somehow turn out all right. But wishing won’t make anger go away, so such hope is actually an obstacle.

We have to simply be willing to go on working with our anger, without expectation that others will become nicer to us if we do so.

The truth is, anger is very hard to overcome, and the job of seeing through it takes a lot longer than you think. Even when you believe you are finally finished with anger, subsequent events will prove that you’re not. Hope can breed laziness and even impatience. Yet patience, which requires an active courage, is what you need the most. So, internally, you really do need to have the commitment to go on working with your anger. You even need to take some delight in this work, because if you view anger as an entirely negative thing that a nice person like you shouldn’t be feeling, and you’re hoping that your spiritual practice will swiftly purify it from your heart, then the shock and disappointment you’ll feel when this turns out not to be the case will be a major impediment.

Working on your anger in the hope that this good work will somehow cause the other person to be different will also likely not pan out. Of course it does sometimes happen that when we soften, the other person does too. On the other hand, it’s very probable that this other person has a life larger than simply their interactions with us, and that the causes of this person’s anger are deeper and more extensive than our interactions with him or her. So we have to abandon hope and simply be willing to go on working with our anger, without expectation that others will become nicer to us if we do so. In fact, our efforts will probably pay off—but only when we stop hoping they will!

Don’t Poison Yourself

Poison in this case means self-centeredness. Although this is changing, it’s taken as a virtue in our culture to look out exclusively for yourself and compete against the many others who are vying with you for a place in the sun. Of course each of us does have to be responsible for ourselves and not expect others to take care of us. But, at the same time, it’s clear that excessive self-concern is counterproductive. It leads to paranoia, greed, and negative personal and social consequences.

The antidote to this poison is a wise concern for others that will balance self-concern. This balance is not a mathematical equation, a tortured compromise, but rather a naturally wise way of being. Take, for instance, a parent who is primarily concerned for his or her child’s welfare. Without some healthy self-concern, the parent’s concern for the child can’t be sustained. If the parent doesn’t take care of his health and psychological well-being, which requires a modicum of happiness, how is he going to do a good job caring for his child? If he’s grumpy, ill, and depressed, how well will he care for his child? So self-concern is not bad—it is required. But when self-concern is practiced as an end in itself, and not for the sake of others, it easily becomes poisonous. We can literally become poisoned with self-obsession.

To practice this slogan is to notice that when we become defensive and aggressive, it’s usually because of the poison of self-concern. Imagine how your experience of anger would be different if in a moment of anger you remembered the slogan “Don’t poison yourself” and immediately turned your attention to others—maybe even to the person you are angry with. How is it from his or her point of view?

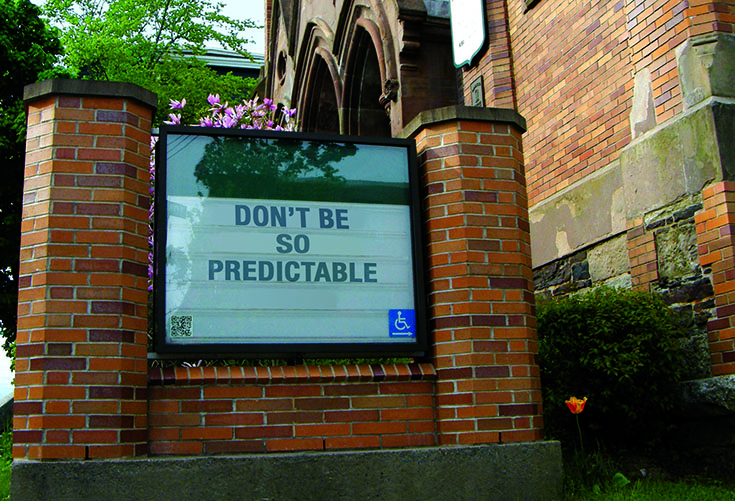

Don’t Be So Predictable

This slogan is the complement of “Don’t figure others out.” It means don’t be so sure that you have yourself figured out. To do spiritual practice seriously is to cultivate a sense of openness and possibility—in relation to others and especially in relation to yourself.

Most of us have plenty of evidence, over a lifetime of experience, that we are this way or that way. We are an angry person. A compassionate person. We are cheerful, phlegmatic, depressed, repressed, expressive, extroverted, introverted. All this is fair enough. We have genetic predispositions and we have been formed by culture, family, and habit. That conditioning doesn’t just dissolve because we want it to, but we are also living creatures with the capacity to respond creatively to what happens to us in any given moment. We all know this. None of us believes that we are 100 percent of the time doomed to have the same reaction to things we have had before. Life is various. We have free will. The whole idea of spiritual cultivation—or education in general, for that matter—is that we can change.

But most of us have a commitment to proving the opposite. We take pride in being the way we say and think we are. Even when we say we want to change, a deeper look shows us that while, yes, we do want to change, we are also so committed to, and comfortable with, the way we have defined ourselves that we sneakily work against the changes we so fervently want to make in our lives.

The slogan “Don’t be so predictable” asks us to examine this sneaky phenomenon. And to be honest about it. To notice, let’s say, in the case of anger, our generic response, whatever it is, and pay close attention to it—not simply to mindlessly repeat it time after time.

Let’s say that when we get angry, we clam up. We observe ourselves doing this and we investigate. Is this just an old habit that we have in fact outgrown? Where does it come from? Do we like it or dislike it? Do we find comfort in it? How does it feel in the body, in the breath? Is something else—in this moment—possible? Could we be a little more creative, a little less lazy, in the way we respond?

Challenging ourselves in this open-ended and curious way, without expectations or mandates that it be this way or that way, is practicing this slogan.

Insofar as anger always presents us forcefully with the possibility that we could challenge our usual way of doing business, it can be a very helpful reminder of who we are now and who we might become. Anger is an acupressure point in the heart. It might feel sore and raw when it is bumped, but that’s good. If we know how to be patient with the pain, how to gently and skillfully massage it, we can be healed—by anger itself.