In 1960, at the age of forty-seven, the great Dzogchen teacher Chatral Sangye Dorje Rinpoche (1913–2015) stood before the Mahabodhi Stupa in Bodhgaya, India, palms joined, and vowed never to eat meat again. He would be the first Tibetan lama in exile to become vegetarian. The glaring contradiction between his wish to benefit all sentient beings and the consumption of their flesh had become untenable.

“Knowing all of the faults of meat and alcohol,” he said, “I have made a commitment to give them up in front of the great Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya with the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions as my witnesses. I have also declared this moral to all my monasteries. Therefore, anyone who listens to me is requested not to transgress this crucial aspect of Buddhist ethical conduct. If we eat meat, we break the vows we take when we go for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. When we eat meat, we have to take a being’s life. So I gave it up.”

Over the next fifty-five years, until his death in 2015 at the age of 102, Chatral Rinpoche inspired thousands of people to give up meat, and whole monasteries in India became vegetarian at his urging. All of Rinpoche’s retreat centers are strictly vegetarian, and even his Vajrayana feast offerings are purely vegetarian. In 1988, Rinpoche ordered that the Nyingma World Peace Ceremony in Bodhgaya, which draws tens of thousands of people each year, be strictly vegetarian. In his words: “There is no better prayer or worship we can offer to Lord Buddha than being thoughtful, kind, compassionate, and abstaining from taking the life of any fellow human being, animal, bird, fish, or insect. Trying to save any life from imminent danger, or trying to mitigate their pain and suffering, is one step further in the active practice of loving other living beings.”

“The Buddhist precepts were not invented to deprive us of life’s delights; they were designed to help us limit our negative actions and efficiently traverse the path to awakening.”

During Chatral Rinpoche’s life, whenever someone came to him and announced they were giving up meat, he would beam with happiness and wrap a celebratory scarf around their neck. Rinpoche’s daughter, Semo Saraswati, explains: “The merit of building temples and buddha statues and stupas or whatever other positive actions you might undertake pales in comparison to the merit of saving a sentient being’s life…. Eating meat with one hand and saving lives with the other hand really doesn’t look very good. In fact, when it comes to saving lives, the very best way to do that is to not eat meat ourselves.”

The first of the five precepts that form the basic code of Buddhist ethics is to refrain from taking life. When we decide to follow the path mapped out for us by the Buddha, the first thing we do is vow not to kill anyone––no person, animal, bird, fish, or insect. When we take the bodhisattva vow, we promise to attain buddhahood in order to protect and free all sentient beings. We vow to make them happy, and we pray to be their guardians, their allies, their refuge. If we then sneak up behind them and kill them, what kind of guardians are we? The Buddha addresses this subject in detail in the Lankavatara Sutra, where meat-eating is referred to as “the root of great suffering.” Buddha declares: “For innumerable reasons, the bodhisattva, whose nature is compassion, is not to eat any meat.”

Many Mahayana Buddhists around the world already observe a vegetarian diet, especially in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Historically, the climate on the high plateau made it almost impossible for Tibetans to be vegetarian, yet there have always been intrepid Buddhist masters who renounced meat-eating and propagated the practice of vegetarianism. Machig Labdrön, the eleventh-century female practitioner of Chöd, said, “For me, eating meat is out of the question. I feel great compassion when I see helpless animals looking up with fearful eyes.”

Rigdzin Jigme Lingpa (1730–1798), overwhelmed by the immeasurable suffering of animals, said, “I beg you with tears in my eyes––all you who love me, do not kill even to save your own lives!” His disciple, Jigme Gyalwe Nyugu, upon receiving an offering of freshly slaughtered mutton, felt like a child whose own mother’s flesh had been set before him. He could not bear to look at it, let alone eat it, and he never touched meat again.

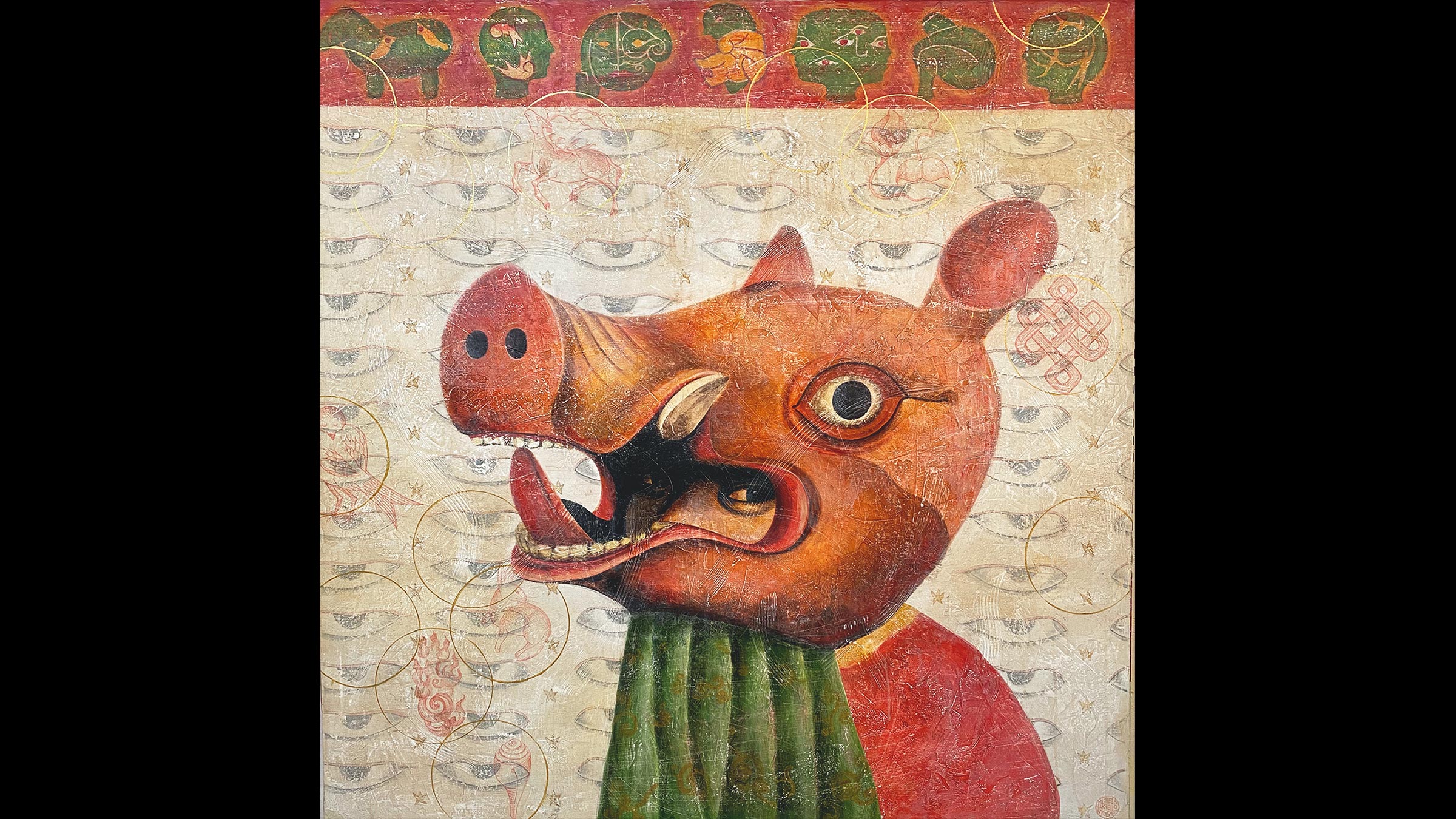

Nyakla Pema Düdül (1816–1872), who famously dissolved his body into rainbow light at the end of his life, describes a vision that prompted him to give up meat:

The Great Compassionate One appeared in the sky in front of me and said, “You have made some progress on the path and acquired some knowledge, yet you are lacking in love and compassion. Compassion is the root of the Dharma, and with compassion, it is impossible to eat meat. A person who eats meat will experience much suffering and illness. Look at the miserable ones! Everyone is experiencing suffering according to their deeds…. One who gives up meat will not experience this suffering. Instead, the buddhas and bodhisattvas, gurus, devas, and dakinis will rejoice and protect you.”

In modern Tibet, several vegetarian lamas have been active in protecting animals and advocating for a vegetarian diet. Khenpo Jigme Püntsok (1933–2004), who founded the famous Larung Gar in Serta, started the anti-slaughter movement, and his student Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö is a vocal proponent of vegetarianism who frees hundreds of slaughter-bound sheep and yaks every year.

In response to those who invoke Buddhist tantra to defend their meat-eating, Chatral Rinpoche said: “If you have the power to bring an animal back to life after it is killed, then it is fine for you to eat meat.” Likewise, Jigme Lingpa wrote, “In a tantric context, it is wonderful if someone has given rise to the power of concentration, so that they are not tainted by obscurations and are able to benefit beings through a connection with their meat and blood. But I do not have this confidence.” If even highly realized masters such as Jigme Lingpa recognize their powerlessness to benefit beings through eating their flesh, then certainly ordinary beings like us should steer clear of such self-aggrandizing delusions.

Khenpo Tsultrim Lodrö explains: “In Vajrayana, the proper way for ordinary people to accept the sacramental substances of samaya [Sanskrit: tantric vows] is through visualization practice, not to actually eat meat or drink alcohol…. If you are given a big piece of meat during the ganachakra [Tibetan: tantric feast], just take a piece no larger than the size of a fly’s leg and give the rest back…. Never allow yourself to freely chew down on chunks of meat or gulp down alcohol.”

Chatral Rinpoche went on to live an extremely long and vigorous life, and his vegetarian diet and tireless efforts to rescue fish, birds, and animals from untimely death certainly contributed to his longevity. This was not all, of course. Rinpoche was a peerless Dzogchen yogi who dedicated his entire life to the Buddha’s teachings and reached the pinnacle of realization. He once proclaimed: “If you have no concepts, you have no sickness.”

The Buddhist precepts were not invented to deprive us of life’s delights; they were designed to help us limit our negative actions and efficiently traverse the path to awakening. Taking a vow not to kill helps us bring awareness to our actions, our conditioning, and our craving, and it opens us up to the causes of suffering and to compassion, so that we can minimize the harm we cause. For those who are unable to abstain from meat, if it is possible to give it up for a day, or even for a few hours, the merit of this compassionate act can be dedicated to the happiness and liberation of all beings. For those who do maintain a vegetarian diet, we must not allow this to fuel some phony sense of spiritual superiority.

Let us walk the path together with humility and kindness and dedicate our collective efforts to the peace and happiness of all beings.