“We live in the age of the refugee,” according to Chilean playwright and human rights activist Ariel Dorfman, and the daily onslaught of news seems to confirm his grim observation. From crises in Europe and Asia to walls along the Mexican border, refugee and migrant issues are among the central concerns of our time. These days I find myself reflecting on how they relate to my dharma teaching and practice as a Jodo Shinshu Buddhist. Perhaps this is especially so because my lineage emerged from the experiences of exile and suffering of our most important founders, Shinran and Rennyo.

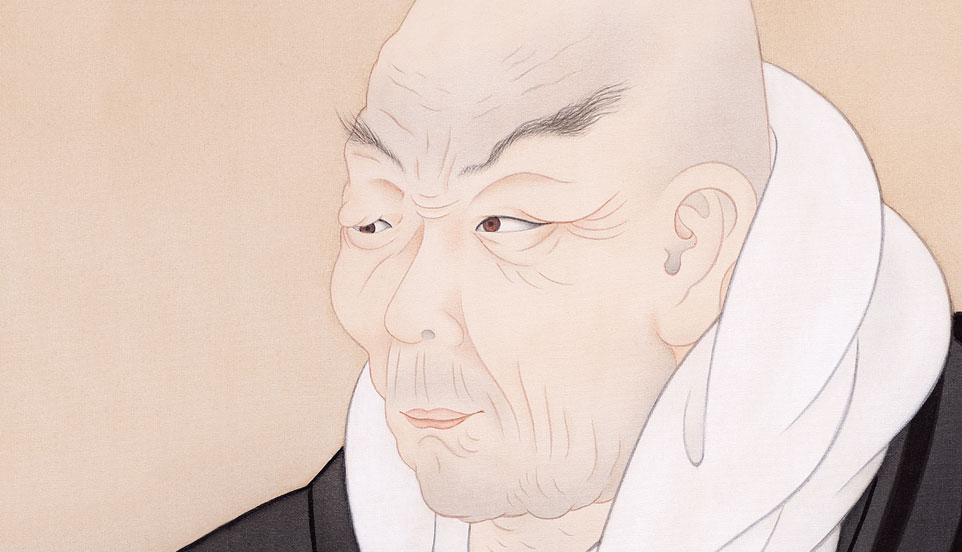

Shinran, the thirteenth-century founder of the Jodo Shinshu (Shin) school of Buddhism, lived in an age of profound disruption, with civil wars, foreign invasions, plagues, and natural disasters. He was orphaned at the age of nine and forced to enter the monastery when his relatives could not provide for him.

Shinran practiced Buddhism for twenty years at the elite Tendai complex on Mt. Hiei before finally joining a new community focused on the Pure Land path. This radical movement preached buddhahood for all beings and pushed back at the strict hierarchical order of medieval Japan. Inevitably, followers of that movement were persecuted. Rivals trumped up charges and the community was outlawed. Some of its members were executed, while Shinran, his elderly teacher Honen, and several of his peers were stripped of their ordinations, branded as criminals, and forced into exile far from their homes in Kyoto. Shinran, for having sought a path that was open to all, found himself a refugee in the remote snow-bound province of Niigata.

Exile was a bitter punishment for Shinran, but it was also the spark that transformed his dharma teaching. In the distant countryside, Shinran was forced for the first time to live among the common people. What he discovered through his suffering and that of those around him strengthened his commitment to the Pure Land tradition. He refused to stop teaching Buddhism; in fact, his exile gave him the chance to preach to the disenfranchised masses who’d been left out of the Buddhist establishment. His disciples included farmers, peasants, townspeople, merchants, low-ranking samurai, and women. Sitting with them, listening to their problems, he expanded his understanding of the vastness of Amida Buddha’s compassion.

Studying the teachings of Shinran, it’s clear that the persecution, displacement, and poverty he experienced led him to feel solidarity with the neglected, the abused, and the refugee. Oral testimony records an event where he was invited to a feast but did not sit with the high monks, as was his right. Instead, he went and sat among the commoners and novices, eating with them and treating them as peers, a major breach of medieval social protocol.

Shinran often adapted his writings into forms that his illiterate followers could more easily access. He wrote letters in ordinary language that could be read aloud to gatherings of peasants, and he crafted a huge volume of songs that expressed the dharma through concrete visual images and concepts anyone could memorize and understand. Here is a translation of some of those songs:

The cloud of light is unhindered, like open sky;

There is nothing that impedes it.

Every being is nurtured by this light,

So take refuge in Amida, the one beyond conception.

The light of purity is without compare.

When a person encounters this light,

All bonds of karma fall away;

So take refuge in Amida, the ultimate shelter.

The radiance of enlightenment, in its brilliance, transcends all limits;

Thus Amida is called “Buddha of the Light of Purity.”

Once illuminated by this light,

We are freed of karmic defilements and attain emancipation.

The light of compassion illumines us from afar;

Those beings it reaches, it is taught,

Attain the joy of dharma,

So take refuge in Amida, the great consolation.

Shinran’s songs taught his followers that Amida Buddha accepts everyone, leaves no one out, can cross any border, and cannot be impeded in the quest to liberate all. This isn’t some stock list of qualities; these were drawn from Shinran’s own experiences and were meant to offer solace to refugees, prisoners, outcastes, and the downtrodden.

The idea of Pure Land as the way to refuge and security is famously embodied in the medieval Chinese Buddhist parable of the white path, created by the master Shandao. In this story, a traveler is lost in the wilderness. Bandits and wild animals attack him, and he runs away until he comes to a riverbank. The channel is filled by two rivers, one of churning waves and the other of raging flames. He sees a narrow white path between the two rivers, but it seems impossible to cross over successfully. Terrified, exhausted, and threatened from all sides, it looks like the traveler will meet his end here at the border. But just then, the voice of Shakyamuni Buddha comes to him, telling him he can make it, and he hears the voice of Amida Buddha calling from the other side, promising he’ll be protected. The traveler crosses over onto the white path and enters the peaceful land of the Buddha, where he lives safely and happily ever after.

This parable, of course, depicts the Pure Land understanding of our human condition, which is fundamentally about the search for a secure home in this world of troubles. The river of churning waves is humanity’s greed, while the river of raging flames is our burning anger and hate. The wilderness is this ordinary world in which we suffer. The other shore is the Pure Land, a way of depicting nirvana in the form of a place offering safety and protection after the misery of wandering and exile. Not surprisingly, the white path was one of Shinran’s favorite stories. For him, it was more than a figment of the imagination, for it described his experiences in terms that felt real.

For Shinran, those who were labeled “evil” or who suffered marginalization and exclusion were the ones who most needed compassion and support. Therefore, Shinran reasoned, the Buddha would naturally take care of them first, before getting around to dealing with the good people too. This was perhaps the most remarkable aspect of his teaching.

Shinran’s radical teaching spread gradually through Japan until the lifetime of Rennyo, known as the second founder of Shin Buddhism. A ninth-generation descendant of Shinran, he was born in the fifteenth century as the illegitimate son of the head of one of the main Jodo Shinshu organizations. His mother was a servant who was sent away when he was six years old; Rennyo never saw her again, despite years of searching for her. He was persecuted by his stepmother, who wanted her own son to inherit the lineage, and he grew up in poverty, eating one meal a day and studying Shinran’s teachings by moonlight.

Due to his natural aptitude, Rennyo eventually did inherit Shinran’s lineage, but his status as master didn’t pave the way for an easy life. He lived through the decade-long Onin War, which kicked off a hundred years of civil war in Japan. He was widowed four times and buried seven sons and daughters during his long life. And, like Shinran, he ended up as a refugee.

In 1465, warrior monks from the monastery on Mt. Hiei attacked and destroyed Rennyo’s temple. Rennyo barely escaped with his life, and for years he was forced to flee from place to place as a refugee and migrant, frequently homeless and always in danger. Finally, he settled in Yoshizaki, a remote and wild community far from those who wanted to stamp out the Pure Land movement.

Rennyo’s poverty and experiences as a refugee left a deep imprint on his dharma teaching. Whereas other leaders of his time taught from high platforms, Rennyo sat on the ground amongst his followers, who were commoners. He personally served them sake and listened to their troubles. Following Shinran’s example, he wrote teaching letters in the vernacular, using common idioms of the time. He stressed anjin, the mind of peace, in a time of war. Through Rennyo’s teaching, forged in his experiences of suffering and exile, Jodo Shinshu became the largest school of Buddhism in Japan.

Modern-day Shin Buddhists have also faced exile and persecution. During World War II, over 140,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated in North America, two-thirds of them Americans or Canadians by birth, and most of those children. Buddhist ministers were among the first to be taken away, with some of them sent to labor camps. Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren, and other Buddhist temples throughout North America and Hawaii were shuttered, with many seized as barracks or subjected to vandalism or arson. Meanwhile, families languished behind barbed wire in searing deserts or freezing mountain valleys, incarcerated simply for who they were. The majority of these victims were Jodo Shinshu Buddhists.

After years of confinement, the War Relocation Authority sought to resettle Japanese-Americans away from the West Coast. The idea was to spread them so thinly throughout the country that they would vanish into the greater population. It was this policy that led to temples in the East, such as in Chicago and Cleveland. The situation was even worse in Canada, where Japanese-Canadians were barred from returning to the West Coast until 1949, long after the war had ended. Thus even after incarceration by their own governments, many families emerged from the camps only to become refugees. Thousands of people were deported, including many who’d never lived in Japan. All told, the internment and attacks on Japanese North American communities dealt a profound blow to Buddhism and would radically reshape it. Now, more than two generations later, the lasting impact of those experiences is still being felt.

In America each year, ministers from the mainland Jodo Shinshu organizations get together for an education series called WeHope. In 2017, the WeHope seminars weren’t focused on Buddhism, as they typically are. Instead, the ministers spent time learning about Islam from local Muslim leaders and visited a mosque. This came about because they recognized that Muslims face strong suspicion and discrimination in our society, that a large portion of the refugees and immigrants seeking entrance to the United States are Muslim, and that as Buddhists we aren’t automatically equipped to understand Islam, Muslims, or the problems they face.

Studying Islam and learning from Muslims provided the ministers, including myself, with a better understanding of the challenges faced by our Muslim neighbors and deepened our compassion for them. We were able to reflect on the challenges and discrimination our own organizations have experienced, and it laid the foundations for correcting misinformation about Islam among our temple members, so that we may lead them in compassionate outreach to Muslim refugees in need.

It’s important that we keep the universally-welcoming vision of Shinran and Rennyo alive. We need to understand the refugee experiences that produced the Jodo Shinshu teaching, and never forget the hard lessons of World War II. We have to make our temples truly welcoming spaces and take care of those in need, around the world and here at home. We need to overcome fear and prejudice within ourselves by relying on the light of nondiscrimination that embraces and accepts everyone, and promises them shelter. In these ways, our refugee past becomes a source of strength and guidance to deal with the problems around us.