In 1972, just after my mother immigrated from Korea to California, she attended a summer camp that gathered young people of different races and religions to build mutual understanding. A smiling sansei (third generation Japanese American) counselor approached her and said, “Welcome, sister.”

My mother stared. She was born just after the end of the Korean War—ten years after Korea gained its independence from Japan. Her parents had grown up during the brutal colonization era, and her grandparents had donated to Korean independence fighters who wore rags as they fought one of the most powerful empires on earth.

My mother snapped at this Japanese man: “I’m not your sister.”

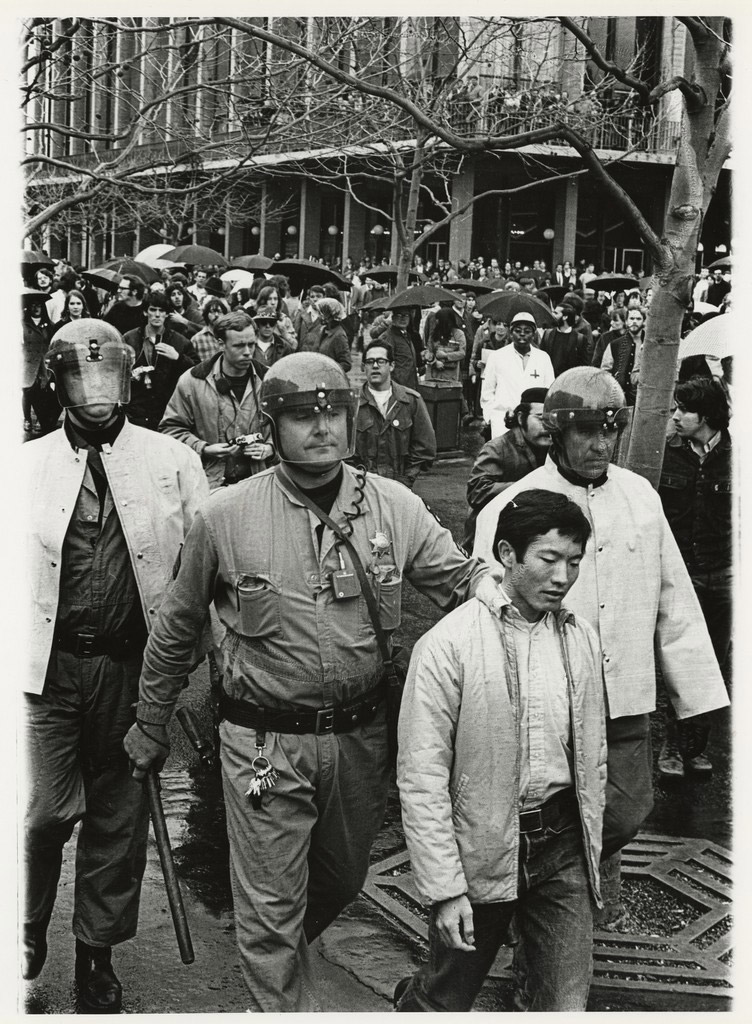

Fast-forward to 2015. Brooklyn, where I’d arrived from California five years earlier, was roiling with protests against police brutality. I needed something to help me with the rage I felt toward the police, the courts, white supremacy—with America itself.

I walked into Brooklyn Zen Center hoping meditation would help calm my burning mind. It did. Yet after meditation came chanting, some of which was in Japanese. Even stranger, most of the people in the room were white. I’d come to escape the colonial histories that shaped me, and now I was in a space filled with them.

I thought: I’m never coming back.

Those two moments, forty years apart, were both shaped by major movements of the sixties and seventies. And though both movements began in the San Francisco Bay Area, they’re rarely spoken of together. The first was the formation of Asian America as a political identity, and the second was the proliferation of temples in the Shunryu Suzuki Zen lineage.

“I wish for an American Zen Buddhism that, like Asian America, builds solidarity and community across differences.”

In 1968, just a few years before my mother attended that camp, students at San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley went on strike. They formed a Third World Liberation Front that demanded Ethnic Studies and more faculty of color. Some of the students were tired of being “Orientals” and adapted a new term: “Asian.” The next decade saw an explosion of activity on campuses and cities: free health clinics, revolutionary study groups, art exhibitions, after-school programs, labor organizing, feminist publications, and a thousand other projects that made up the Asian American Movement.

It was this movement that brought my parents together—two idealists at UC Berkeley in the 1970s. It was this movement that shaped their twenties, as they organized in factories and helped free the wrongfully incarcerated Chol Soo Lee. It was this movement that created or inspired most of the institutions where I later held my first jobs: Museum of Chinese in America, Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and Kundiman. It was this movement that defined “Asian” not as a census category or monoculture, but as a coalition, a strategy, a political stance.

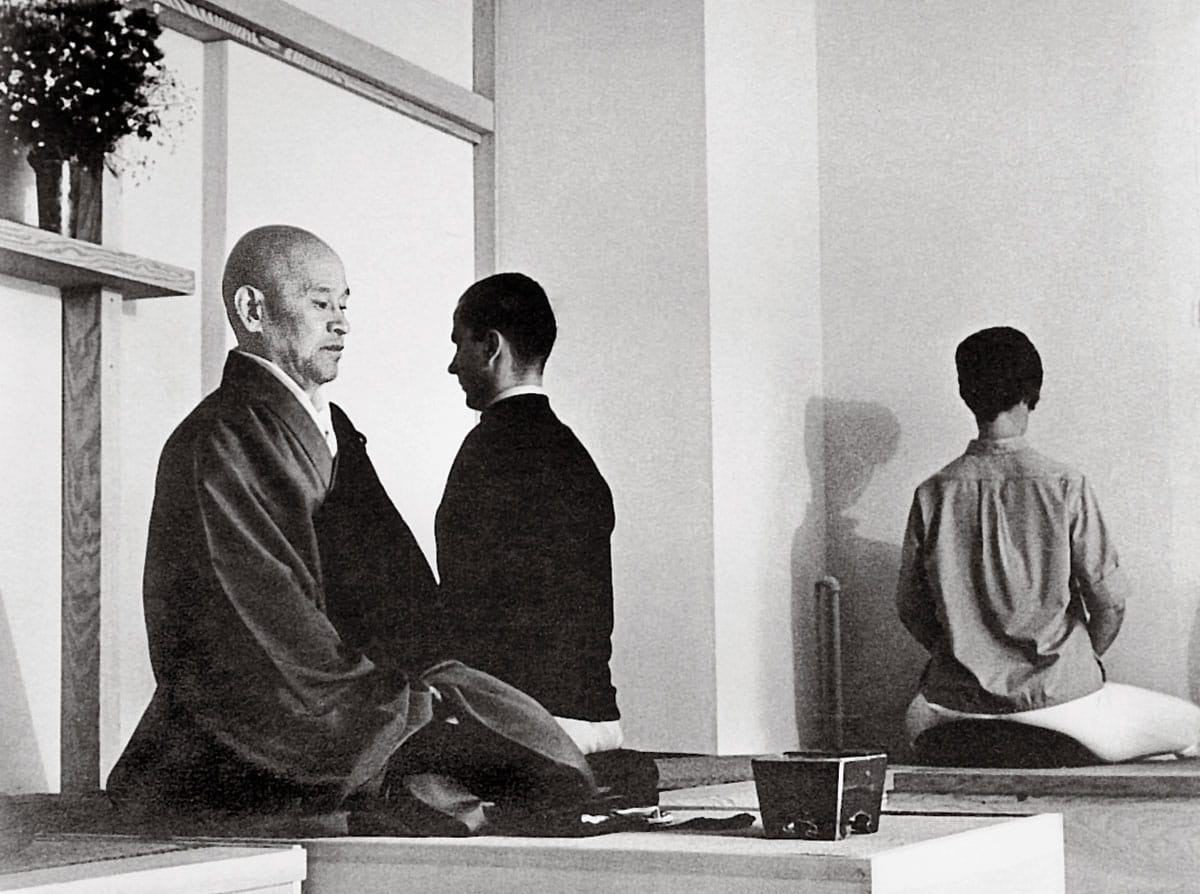

At the same time those students went on strike, new Zen temples began sprouting under the guidance of Shunryu Suzuki. He came to America in 1959 at the invitation of Sokoji, a Soto Zen Temple in San Francisco’s Japantown. A group of mostly white, counterculture, young people began seeking out Suzuki’s teachings. They’d read D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts; they wanted alternatives to the social values and worldviews they were raised with.

Those students began a sitting group, then began to ask for more intensive monastic training. Suzuki turned his attention toward the new San Francisco Zen Center they founded in 1962, which quickly expanded into two residential centers, Tassajara and Green Gulch, then acquired a building down the street from Sokoji. Teachers who trained at Suzuki’s three centers went on to found temples around the country. There are now more than sixty “Branching Streams” affiliates offering the same practices that Suzuki taught his students, including Brooklyn Zen Center where I first sat.

It’s striking that the new Asian America and the new American Zen flowered in the same city, driven by the same countercultures, yet barely interacted. Early Asian American politics were largely influenced by leftist politics. Young organizers saw the material struggles of their communities: aging seniors losing their homes, garment workers facing exploitation, Asian neighborhoods with little access to healthcare or fresh produce. And it seemed as if a global leftist wave, from China and Vietnam to Cuba and Ghana, was remaking the world for the better. Marx famously warned that religion was the “opiate of the masses,” and for many of those organizers, politics was irreconcilable with faith, activism a world apart from contemplation.

Meanwhile, the early San Francisco Zen Center students were studying Japanese culture but not necessarily Japanese America. They studied Buddhist sutras but not the recent history of internment, Eihei Dogen and Hakuin Ekaku but not Fred Korematsu or Yuri Kochiyama. One way to see the divide between Sokoji and San Francisco Zen Center is a failure to organize across difference: to bring issei and nissei elders together with baby-boomer hippies and the Beat Generation, to create a multiracial sangha where all of those lived experiences were seen and valued. Instead, there was the two temples split.

Now we have a chance to braid these histories back together. Rev. Dana Takagi suggested in a recent lecture, marking one hundred years of Soto Zen in America, that we might see the Asian American Movement as “studying the self,” Eihei Dogen’s definition of the path of awakening. By understanding our histories and organizing in response, we turn toward liberation through and from our identities.

The scholar and poet Russell Leong, in a tribute to the poet Janice Mirikitani, chides those early convert Zen students: “Sure, a typical Zen koan and a tap on a bald pate could bring enlightenment, but a simple meal for a homeless person in San Francisco’s Tenderloin could immediately fill the belly and bring peace of mind.” Perhaps the Asian American Movement was taking a direct path to practice, embodying compassionate action.

The merging of dharma and action is, after all, what drew me to Brooklyn Zen Center. My teacher, once an anarchist and part of the Zapatista movement, brings that background to Brooklyn Zen Center when he speaks of collective liberation, when we host teach-ins on prison abolition or hold “undoing patriarchy” workshops.

I can no longer understand dharma separate from social engagement, nor do I want activism separate from compassion and wisdom.

I must hold these diverse expressions without discarding any: Sokoji’s Japanese American roots alongside the converts who founded my temple; the challenges of sitting in a majority-white Zen space alongside the beauty of building a multiracial community; ancient sutras as well as contemporary studies of patriarchy and colonialism.

My mother encountered Asian American on that day in 1972. Her impulse was to write off the Japanese American counselor, but instead she taught him about Japan’s colonization of Korea and learned from him about the internment camps. She went on to embrace the coalitions of the Asian American Movement and organize across race, class, and age.

I encountered American Soto Zen that day in 2015. My impulse was to run, yet I found myself returning and returning, tracing the messy threads of my history as I studied the self. Now my life’s work is to include all these complexities, both as a Zen priest in training and as the administrative director of Brooklyn Zen Center.

I wish for an American Zen Buddhism that, like Asian America, builds solidarity and community across differences. I wish for Asian American organizing, scholarship, and art to hold the cosmologies and belief systems of our ancestors, many of whom were shaped by Buddhism. I believe it’s possible because these two traditions—American Zen and the Asian American Movement—have each pointed me in the same direction: to form vibrant, engaged, and whole communities, and through those communities, to work for the liberation of all.

This article was published in the June 2024 issue of Bodhi Leaves: The Asian American Buddhist Monthly.