Question: A few years ago I discovered a book called Mind Development by Ven. Phra Tepvisuddhikavi. I began to study and practice its teachings on anapanasatibhavana, mindfulness based on breathing. With my first effort I was able to achieve one-pointedness and the resulting ecstacy (piti) to an intense degree. However I did not maintain a regular practice habit, and usually limited my practice to thirty minutes per session. I now find it more difficult to develop one-pointedness and often fall asleep. What is it that I am doing, or not doing, that I can no longer develop meditation as I had in the beginning? I’ve tried meditation with my eyes open but feel somewhat distracted. I am more interested in the shamatha aspects of the practice. Can you please help me find that one-pointedness that I found so easy at the beginning?

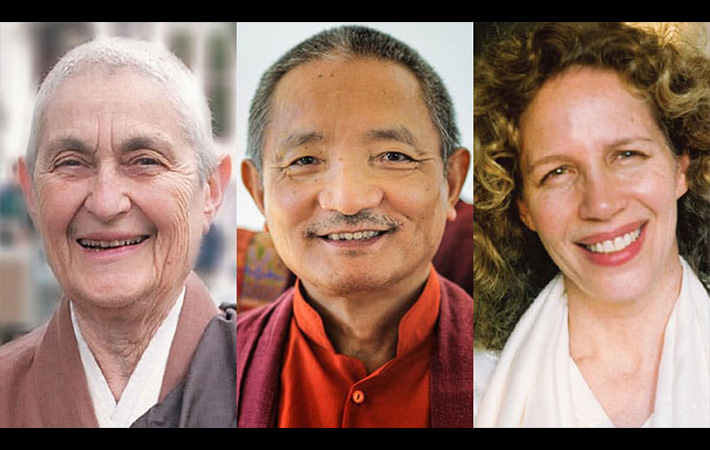

Tulku Thondup: There are two aspects to every Buddhist meditation: letting our mind dwell one-pointedly, like a mountain, when we are focusing on any meditative field, and seeing whatever we are meditating on as it truly is. The first aspect is tranquility (shamatha); the second, insight (vipashyana).

Unless there is a reason, it is impossible to lose an experience of true mindfulness of the breath. However, if we stop meditating for awhile and develop bad habits such as giving in to afflicting emotions, an unhealthy daily lifestyle or a tendency to wander, such conditions might overwhelm us. Or it may be that we are not meditating with the correct approach. It is not uncommon for people to enjoy one-pointedness, clarity and/or joy when experiencing a meditation result for the first time. But if our mind becomes attached to or distracted by these sensations, those qualities will fade away like marathon runners in the distance, and we will find ourselves back at square one. If we are not distracted by or attached to our meditation experiences, and if we stay with that same meditation, the sensational aspect of our experience will unite us with the inner union of openness, clarity and joy.

Please continue your meditation and stay with it, without any expectation of good results or any doubt about its success. When you experience any meditative result, don’t get excited by or attached to it, but stay naturally in the flow of the awareness of the experience, and dwell with it as if you had merged into it as one. Then everlasting authentic benefits will be yours to enjoy.

Start your meditation with joy and thankfulness for the opportunity. This attitude will dissipate any indifference or dullness that you might be feeling and will energize the strength of your mindfulness. Meditate with total confidence for multiple short periods, stopping before you fall asleep or get distracted. That way a habit of quality meditation will take root in you. At the end of the session, dedicate the merits of your meditation for the sake of all mother beings. Giving away the merits will create more merit that will, in turn, ensure more successful meditations and results.

Narayan Helen Liebenson: If you are looking for deep levels of samadhi, a half hour a day is probably not going to do it, unless you have extremely unusual karma.

However, to put your question into a larger context, you might bring your attention to the Second Noble Truth, which is, of course, that attachment is suffering. Because you had such a delightful experience on your first try, the tendency of the mind is to cling to it and direct your efforts toward getting that experience back. However, the law of impermanence reveals that this is not possible. This is a great opportunity to see impermanence clearly and to practice letting go.

Freedom lies in letting go of all experiences, even positive meditative states. Our practice can be focused on the attempt to get high or it can be directed towards that which is lasting and indestructible. I encourage the latter approach. Be aware of trying to repeat an experience. Be aware of disappointment and discouragement, and of trying to attain a particular state of mind. You will be well on your way.

Blanche Hartman: I am sorry that I cannot tell you how to return to a state of mind experienced in the past.

I have come to consider moments of clarity such as you describe as gifts of the universe rather than personal achievements. All I can do is cultivate a calm, non-grasping, non-discriminating mind that is ready to receive these gifts. My teacher always spoke of “no gaining idea” and “no goal-seeking mind.” He also said, “Zen is making your best effort on each moment forever.” “What is it to make effort with no gaining idea?” became my principal koan for many years.

In the prologue to his book Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki Roshi said, “For Zen students the most important thing is not to be dualistic. Our ‘original mind’ includes everything within itself. You should not lose your self-sufficient state of mind. This does not mean a closed mind, but actually an empty mind and a ready mind. If your mind is empty, it is always ready for anything; it is open to everything. In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few. If you discriminate too much, you limit yourself. If you are too demanding or too greedy, your mind is not rich and self-sufficient.…In the beginner’s mind there is no thought, ‘I have attained something.’ All self-centered thoughts limit our vast mind. When we have no thought of achievement, no thought of self, we are true beginners. Then we can really learn something. The beginner’s mind is the mind of compassion. When our mind is compassionate, it is boundless. Dogen-zenji, the founder of our school, always emphasized how important it is to resume our original mind. Then we are always true to ourselves, in sympathy with all beings, and can actually practice.”

For the benefit of all beings, please keep making your best effort, with no gaining idea. Meet each moment as-it-is and accept with gratitude whatever it has to offer. Good luck!