Question: Some teachers say that if you’re having difficulty with your meditation you shouldn’t force yourself to stay on the cushion. How do you know when you’re forcing your meditation, instead of applying proper effort? Should you continue with the practice if you’re feeling a lot of resistance and your mind is racing? Do you recommend short periods of meditation or longer ones?

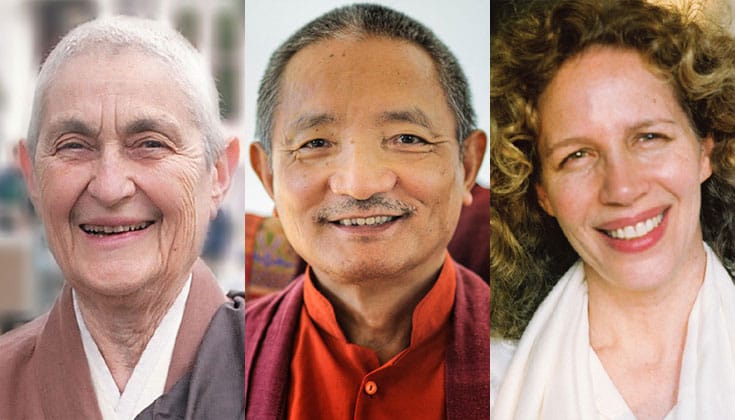

Tulku Thondup: Whether you should shorten your meditation periods or not depends on why you are having a hard time meditating. If the reason is that you lack inspiration and confidence to meditate—whether because you don’t have enough physical or mental energy, your concentration span tends to be short, or you are under the pressure of strong, persistent, mental and emotional resistance—then it is better to meditate for shorter, more frequent periods. Once you start to get a real taste for meditation and experience its benefits, your inspiration to do it will grow, as will your meditation energy. When that happens, you must expand the period of meditation and unite your life as one with the meditation.

However, if the reason you’re having trouble meditating is that you are letting your mind indulge in pleasures and other distractions or that you have let your mind become a lazy “couch potato” and made little effort to get into the habit of meditating, then you must force yourself to sit in meditation. Also, think about the rareness of the precious human life that you are enjoying. Contemplate the impermanence of life, suffering and the changing character of samsara, and the amazing blessings of liberation. Such thoughts will propel and inspire your mind to meditate. Reading exalted scriptures, or biographies of great masters, and witnessing or experiencing suffering, are also great sources of inspiration.

Life is too short to waste. We have run out of excuses to waste any more of it. We must use all skillful means to inspire ourselves to dharma and to practice it so that we can awaken the awareness of peace and joy, not only in ourselves, but also in all mother beings.

Narayan Liebenson Grady: There is no set formula that applies to all practitioners. Shorter periods of sitting are fine, longer periods of sitting are fine. How to deal with resistance is the bigger question. A major part of practice involves learning how to work with resistance skillfully. This means learning how to befriend the experience of resistance, instead of viewing it as something other than practice that we have to get rid of in order to be able to practice.

Gradually we learn how to make our way gracefully through resistance by gently opening to it and seeing it as integral to practice. We find ourselves in a struggle when we hold a model in our minds of how the practice should be going. Try to be aware of resistance when it occurs and don’t worry if the mind is racing. We are responsible for our efforts in practice, not the results of practice, because the results are beyond our control.

One exercise that you can try as a way of learning how to work with resistance is to sit through three instances of experiencing resistance. In other words, sit and apply your usual method of practice. When you want to get up, continue to sit and be aware of the experience of wanting to get up. Then continue with your method. When you experience wanting to get up for the second time, stay in the sitting posture and be aware of wanting to get up. Then continue with your method. After the third time of being aware of wanting to get up, get up. This is a way to learn how to be less intimidated by resistance.

Blanche Hartman: Before speaking about how long I recommend sitting, I would like to say something about how I recommend sitting. As for the body, aim for a posture which is upright, balanced and at ease, as opposed to uptight, unbalanced and tense. You may sit on a bench, a chair or a zafu, depending on your physical capacity or limitations. If on a chair, be sure your feet are planted firmly on the floor or cushions and that you are not leaning back. Sit on your “sitting bones” so that you have a stable foundation for a balanced posture. If on a zafu, arrange your legs to provide a stable and sustainable base for sitting. I prefer half- or full-lotus for its stability and support of the back, but don’t force it as you can injure your knees if your hips are not yet open enough for lotus. Instead, begin with Burmese (one leg in front of the other) or seiza (kneeling) posture, or alternate between the two. If sitting cross-legged, alternate which leg is on top or in front of the other in order to develop flexibility in both hips.

Once you have arranged your legs, lean forward at the hips and rotate your pelvis in order to lift the tailbone and then replace your buttocks on the cushion, chair or bench. This will give a lift to your spine and a slight inward curve to your lower back. Continue to lift or lengthen your spine all the way up to the crown of your head and let your shoulders hang loosely from this central support. Place your right hand, palm up, touching the lower abdomen (supported on the foot if in lotus) and your left hand, palm up, on the right, making an open circle with thumb tips lightly touching.

Balance is the next point and is very important in being able to remain upright and at ease. Let the weight of your head be supported by your spine by moving it back so that your ears are over your shoulders (keeping it level so that your chin is not high). If your head moves out in front, the muscles of your upper back will become tired and painful from holding it up. Let your torso and head be supported by the hips by not leaning right or left, forward or backward. Even slight leaning will require a tensing of all the muscles in your torso to counteract gravity. It is wise to check these points from time to time.

As to the disposition of the mind in meditation, let it be non-judgmentally aware of the experience of the present moment without grasping the pleasant or averting the unpleasant. When your attention wanders to another time or place, return it to here and now. As breath, posture and physical sensations are happening now, they are helpful objects of awareness. Thoughts and feelings are also happening now; simply be aware of them without getting caught in discursive commentary.

Now, as to your original question, how long should one sit? If you are beginning, I think it may be more beneficial to sit shorter periods so that you don’t fall into “holding still.” This makes for the tense, tight, painful situation I warned against in the beginning. It is the opposite of my understanding of zazen, which aims toward openness and ease, more and more openness of body, heart and mind. Rather than holding still, we allow ourselves to settle into stillness. As one becomes more flexible in body and mind, longer periods may be beneficial.

When I first began meditating, Suzuki Roshi said, “You can sit five minutes a day, or ten.” I think it is better to develop a daily sitting practice, even if it’s short, than to sit for longer periods only sporadically because you are struggling with resistance. If you are drawn to meditation practice and are also struggling with resistance, a little curiosity about the source of the resistance may lead to insights about how you construct self-view.

Rejoice that you have had the good fortune to discover the possibility of practice and trust that in you which is drawn to it. Don’t force yourself, but don’t give it up when there are difficulties. Persevere and find your own way with the help of a good spiritual friend.