Question: The doctrine of no-self seems to contradict the idea of rebirth. Did the Buddha address this contradiction? How do teachers reconcile this when teaching students like me who’ve grown up with a modern Western mindset?

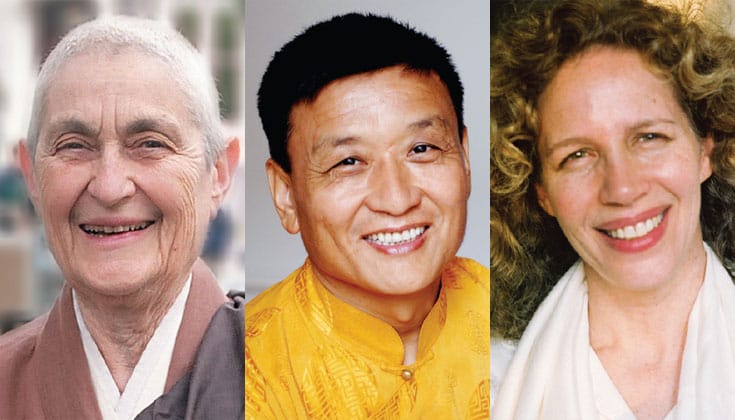

Narayan Helen Liebenson: This is a question that has befuddled countless practitioners and scholars. If there is no self, then what is reborn?

In countries where Buddhism is the predominant religion, rebirth is simply accepted as a fact of life, whereas from a Western perspective it requires a huge leap of faith. I am aware that my own belief in rebirth, as intuitive as it may feel, is still a belief and can’t be proven until I die. It is possible I’ll be surprised.

Fortunately, the teachings are not meant to be believed blindly but rather taken as arenas of inquiry. They allow us to investigate the causes of suffering as well as the path to end suffering. In the Middle Length Discourses, the Buddha says we need only understand the four noble truths, no matter how interesting other questions might be.

The Buddha didn’t try to prove that there was such a thing as rebirth. He simply recounted what happened on the night of his awakening, which is that he saw endless past births and deaths. By the end of the evening, he knew the cycle of suffering had ended. If we trust the Buddha, and if we trust in the teachings that have served us thus far, we may also be able to trust the story of the Buddha’s awakening and take it as our story as well.

The Buddha refused to answer the question about whether there is a self. What he did say is that this mind–body process cannot be clung to as being “me,” “mine,” or “myself.” The Thai teacher Buddhadasa said that being concerned with future lives is for simple-minded Buddhists, because what matters is “ending the rebirth of the ego. It will keep being reborn in mind–body in your daily life until there is the realization of the emptiness of ‘I’ and ‘my’.” Buddhadasa emphasized the necessity of seeing into the emptiness of “I” and “my” right here and now.

So from one point of view, there may indeed be past and future lives. But from another point of view, it doesn’t really matter. What breaks the cycle of suffering is the transformative understanding of karma and not-self—understanding that wholesome mind states bring wholesome results and unwholesome mind states bring unwholesome results, and seeing through the belief in a permanently abiding unchanging self.

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: It is not true that there is no self. There is no inherently existing self. When you realize there is no inherent existence of the self you begin to connect with your conventional, relative existence. Usually we don’t realize our relative existence because we experience ourselves as solidly existing. This seemingly solid self, or ego, is referred to as the karmic conceptual pain body.

Basically, ego is the mind that imagines itself and its stories to be real. When we awaken the eye of wisdom, we are able to recognize the truth of impermanence and recognize that this self, this ego, this pain body, is actually a collection of experiences that are in constant flux or change from moment to moment. When we experience the illusory nature of our pain body, we realize the conventional nature of the self. This is referred to as the recognition of emptiness—empty of the imputation of a fixed self. This recognition supports us to become free from the grasping mind, the mind that experiences our self and our world as solid and fixed.

The way ignorance sees, the way the conceptual mind experiences the self—that self doesn’t exist. Recognizing this illusory nature, one cuts the root of ignorance, which is basically failing to recognize the truth of emptiness, which is the emptiness of the inherently existing self. This recognition is not a product of thought but is a direct experience. I often guide my students to experience directly the stillness of the body, the silence of speech, and the spaciousness of mind. This is our inner refuge. This is the healing space in which the production of ego—the thoughts, feelings, emotions, sensations—is free to arise, dwell, and then dissolve. Seeing this from moment to moment is recognizing the transitory and illusory nature of all phenomena, which includes the self.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: The notion of rebirth is associated with the understanding of cause and effect, that is, the understanding that all volitional actions (karma) will bear fruit (vipaka). In other words, actions have consequences, but intention is critical. Actions taken with a wholesome intention will produce a wholesome result and actions taken with a harmful intention will produce an unwholesome result. If the action does not mature into a result in this lifetime, it will do so in a subsequent life. Thus, rebirth. The teaching that if we initiate a cause we will experience the effect is important in encouraging ethical conduct and virtuous actions aimed at reducing suffering in the world.

The question is: what is reborn? I once asked a teacher, “What continues life after life?” He responded, “Never mind what continues life after life. What continues moment after moment?” The Buddha taught that our entire experience is accounted for in the five aggregates (skandhas): form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. There is no “person” to be found in the sense of a permanent essence or underlying substance.

In response to your question—“Did the Buddha address this contradiction?”—I recommend an interesting discussion of the Buddha’s response to speculative metaphysical questions in chapter 10 of the Early Buddhist Discourses, edited and translated by John J. Holder, which includes “The Discourse to Vacchagotta on Fire,” Majjhima Nikaya 1.483-488. Basically the Buddha said such questions do not lead to liberation from the cycles of rebirth, so he did not dwell on them.

The bodhisattva vow to live for the benefit of all beings and Suzuki Roshi’s admonition to see Buddha in everyone inspire me. I see the teaching of rebirth as simply a support for morally wholesome conduct, and the teaching of no fixed or permanent self as a description of the constantly changing world I see all about me.