Question: I am relatively new to Buddhism (I have been practicing for about a year) and I’ve been struggling with the balance between study and practice. How should I go about setting up a plan of study for myself? How do I decide what I should study when there is so much material out there, and are there things that I absolutely must study before going on to more advanced material? Also, do you have any suggestions on how I should balance practice and study? Is there an ideal balance between the two?

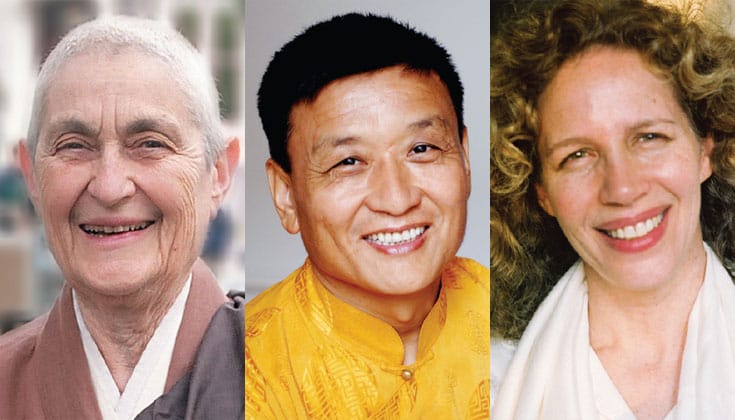

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: I wish I knew a little bit more about you so that I could answer you more specifically. For example, in what tradition have you been practicing? Are you practicing with a teacher or a sangha, or are you on your own? If you do not have access to a teacher who knows you, then I would suggest that you begin by studying the teachings of contemporary teachers in the tradition that you are practicing—teachings that are directed to practicing students. That is, rather than studying writings about Buddhism, study the writings of teachers who are actually teaching their students, face-to-face. There are so many now! Below is just a small sample from one tradition. When I began to practice thirty-five years ago, there were very few Buddhist books in English, so I couldn’t distract myself by reading about practice rather than doing it. Regarding your question about balancing practice and study, I would focus on practice, with study as a guide and encouragement to practice. Ultimately, it’s all about how you live your life moment by moment, so do learn about the basic teachings of the Buddha, but don’t make an intellectual exercise out of it.

For example, if you are practicing Zen, I would recommend Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki or Not Always So, by the same author. Or try Returning to Silence, by Dainin Katagiri; The Way of Everyday Life or The Hazy Moon of Enlightenment, by Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi; Taking the Path of Zen or other books by Robert Aitken; Everyday Zen or other books by Charlotte Joko Beck; The Art of Just Sitting, edited by John Daido Loori; Subtle Sound, by Maurine Stuart; Zen is Eternal Life, by Jiyu Kennett; Three Pillars of Zen, by Philip Kapleau; Opening the Hand of Thought, by Uchiyama Kosho; or books by the Chinese Chan masters, such as Master Sheng Yen or Master Hua or the Vietnamese Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh.

In Buddhism, you will hear of the three treasures or three jewels: Buddha, dharma and sangha (teacher, teaching, and community; or awakened one, truth of how things are, and those who practice together). If you do not have a teacher and practice companions, you may want to look for an opportunity to do some retreats or visit an established community for a period of time as a guest student in order to deepen your practice and speak directly with teachers and other students of the dharma.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: It is essential to have a good balance between study and practice, and the relationship between what you study and the meditation practice you do is important to consider. In the Buddhist monastic traditions of the East, there are clear and established programs of study and practice. The Western student, however, faces a vast sea of information from a variety of Buddhist schools. I will suggest some guidelines.

First, notice what you are drawn to reading and reflecting pon. Find the source of those teachings and see if it is a legitimate tradition, an unbroken lineage where the teachings have been transmitted from teacher to student up to the present day. Look for a complete path with a rich body of literature. In order to dedicate yourself to a path and take it seriously as a life’s pursuit, you need to look deeply and then commit fully. Perhaps this is not always emphasized in the West, where so much information is available.

To study and not meditate is merely an intellectual pursuit. That is unbalanced. Then again, sometimes people don’t study enough. Whatever meditation practice you commit to, your study should support that, so that in your practice you know what you are doing and you have a reference for your experiences. Your study guides your practice, and your practice validates your study. If you are practicing and don’t know where to refer your experiences, you can create unnecessary doubt. And studying without taking your reflections to your meditation cushion and allowing them to ripen as direct experience also sows seeds of doubt.

There is a Tibetan saying, “Listen (thos), reflect (bsam), meditate (bsgom), and experience (nyams).” Sometimes, in reference to the experience, it is said, “Experience and then let the experience go.” Listen in a way that allows you to develop the ability to be less influenced by your projections and speculations. Reflect upon what you read or hear until you understand it, and then meditate until you experience it directly. Often people elaborate upon their experiences and end up in their fantasies. Be careful to avoid this trap. The process of meditation and direct observation can help you to clean and clear the conditioned mind that distorts what you read and learn. Meditate until you experience, and then do not hold on to your experience; let it go. Gain confidence from your experience and deepen your faith in the goodness of the teachings and their effectiveness in lessening suffering.

Narayan Liebenson Grady: Because you are a beginner, I would recommend more practice and less study. Having a framework for the practice is essential for a sense of vision and wise effort. However, if you have a limited amount of time, focusing more on the sitting practice right now would be a better use of your time.

Reading one’s own heart is often harder than reading the best of dharma books. Sometimes people depend too much on secondhand knowledge, rather than relying on direct experience and looking deeply at the nature of their own mind. Thus, to renounce reading for particular periods of time can be quite powerful as long as one is engaged in a serious practice.

Of course, after some years of practice, studying more intensively can be very nourishing. But this means reading in a contemplative way—digesting and applying what has been read—instead of relating to dharma books as a kind of entertainment or as a substitute for practice. Reading and contemplating the original discourses of the Buddha is invaluable. There are many books these days that interpret what the Buddha said in contemporary language, and they can be most helpful. Dharma centers sometimes have suggested reading lists and you might write to a center in your tradition and ask for one. Or, instead of trying to study completely on your own, you could consider taking advantage of a study program, such as those offered at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Finally, if you would like a recommendation for my all-time favorite dharma book, it is What the Buddha Taught, by Walpola Rahula.